Wittenberg, October 31, 1517

Oil on canvas, Signed and dated: E. Crowe, 1864 (lower left)

Eyre Crowe, A.R.A.

English, 1824–1910

Click on links for additional reference information.

Martin Luther truly changed the course of history, but it was English painter Eyre Crowe who captured the defining moment. Wittenberg, October 31, 1517, has long been a favorite of M&G guests for its historical accuracy. “Story paintings,” a common name for the genre of this piece, invite investigation, and recent research on Crowe’s work has revealed that there is “more of the story to tell.”

The obvious historical event being pictured here is Luther’s nailing of the 95 Theses to the door of the University of Wittenberg Chapel. But it may very well be that Crowe purposely wove together additional personages and objects which served to emphasize the crux of the matter which prompted Luther’s action – plenary indulgences offered by the Roman Catholic church.

The prominent horseman on the left, Johann Tetzel, holds in his left hand a grid-like object with dangling metal bulla. The embedded papers, inscribed with numbers representing days or years in purgatory that could be lessened, were purchased by anxious parishioners seeking to relieve themselves or their dead of suffering. Coins clunking in the coffer Tetzel holds evokes the rhyme that still rings through the halls of history.

Worshippers could also acquire relief from anguish by employing a prayer to Mary, Christ’s mother, called The Rosary. In order to count the component invocations, or “tell the beads,” individuals held an object known as a rosary. Rosaries took on many forms (chaplets, ropes, decade and pomander rings) of varying materials (wood, glass, seeds and plastic). Crowe identifies medieval rosary rings reminiscent of a carnival ring toss game by placing examples in the foreground. He continues to add additional weight to his emphasis by sprinkling rosary types, either held or worn, near the significant people in Luther’s life. Research required to accomplish such a historically accurate piece likely led Crowe to such paintings as The Arnolfini Wedding by Jan van Eyck and The Feast of the Rosary by Albrecht Dürer both of which contain prayer beads.

Prominently represented left center and wearing regal garb is Margaret of Münsterberg with her son George III clinging to her skirt. Bereft of her husband, Prince Ernest I of Anhalt-Dessau, and left with three sons too young to assume regency, Margaret undertook her new position as princess regent with vigor and religiosity. Strongly adverse to the Reformation, she organized the League of Dessau. Though unsuccessful in thwarting the spread of the Reformers’ teaching, it is very possible the League exposed her sons to Luther and his doctrine. Letters were exchanged between Luther, Margaret, and her offspring, which resulted in her sons’ adopting the tenets of Lutheranism in their adult years. George ultimately was ordained by Luther, making him the only German prince to be inducted into the Lutheran clergy.

As if to make a final point on the issue of indulgences, the artist places in each of Margaret’s hands a rosary – one a ring and the other a wooden beaded arrangement. A woman of means who could certainly afford some of the extravagant materials used for rosaries of the period, Margaret, however, emulates her sovereign ruler, Charles V, by clutching a poor man’s wooden one.

In Eithne Wilkins’ The Rose Garden Game; the Symbolic Background to the European Prayer Beads, the author details the varying philosophies associated with a worshipper’s choice of rosary materials:

Beauty of material and elaborate workmanship over against ascetic simplicity remains an issue, as might be expected throughout the centuries. The principle of making the external object conform with the interior purpose can be interpreted in two ways. One may feel, as Lady Godiva did in the eleventh century, that it is fitting to count one’s prayers on jewels, for they are being offered to God. Or one may feel that a wretched sinner like oneself should not presume to offer prayers on any but the plainest beads. This sort of self-abasement may even be more effective than any flashing of gems. That was so when in 1532 and again in 1541 the Emperor Charles V, taking part in the Corpus Christi procession at Regensburg, carried ‘ordinary little brown wooden beads’: it was, the commentator pointed out, ‘to mark his humility.’ The ostentation of some people’s display evoked criticism as early as 1261, and fashion was not always on the side of luxury: Emperor Charles V carried ordinary little brown wooden beads…to mark his humility.

Crowe has also included the historical likenesses of other key people from sixteenth-century Wittenberg on the right side of the painting. Katherina von Bora, the nun who eventually married Luther, is present with Luther’s father, mother, and sister. To the left of Katherina von Bora is Luther’s artist friend, Lucas Cranach, the Elder.

Wittenberg, October 31, 1517 is exhibited as part of Luther’s Journey: Experience the History on view in the Gustafson Fine Art Center on the campus of Bob Jones University. Information about the exhibit and the accompanying tour is available here: www.museumandgallery.org/specialized-tours/

Bonnie Merkle, Internal Database Manager and Docent

Published in 2017

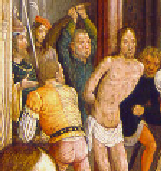

ng sleeve flaps, or even hats into pointed or squared scallops. This trend was especially popular during the late Middle Ages. The man in red at Christ’s crowning with thorns features dagging at the bottom of his doublet (jacket).

ng sleeve flaps, or even hats into pointed or squared scallops. This trend was especially popular during the late Middle Ages. The man in red at Christ’s crowning with thorns features dagging at the bottom of his doublet (jacket). tried to take matters into his own hands by declaring a law that “no Knight under the estate of a lord, esquire or gentleman, nor any other person, shall wear any shoes or boots having spikes or points exceeding the length of two inches, under the forfeiture of forty pence.” The law was ineffective, and the trend lasted until 1480! The man, at right foreground and near to Pilate, models poulaines.

tried to take matters into his own hands by declaring a law that “no Knight under the estate of a lord, esquire or gentleman, nor any other person, shall wear any shoes or boots having spikes or points exceeding the length of two inches, under the forfeiture of forty pence.” The law was ineffective, and the trend lasted until 1480! The man, at right foreground and near to Pilate, models poulaines.  ed for ceremonial occasions as seen here on the soldier kneeling in the foreground.

ed for ceremonial occasions as seen here on the soldier kneeling in the foreground. horns features

horns features a parti-colored doublet. At the beating of Christ, the man to the left of Christ also wears a parti-colored doublet.

a parti-colored doublet. At the beating of Christ, the man to the left of Christ also wears a parti-colored doublet.