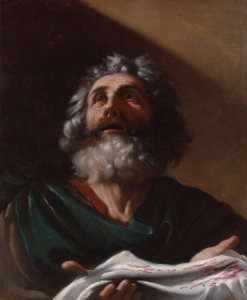

Jacob Mourning over Joseph’s Coat

Oil on canvas, c. 1625

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, called Il Guercino

Bolognese, 1591–1666

The nickname “Guercino” (the squinter) was given to the artist due to an eye defect which in no way deterred his ability or ambition to paint as evidenced by his lifelong production of hundreds of paintings, thousands of drawings, and numerous frescoes. He worked for Pope Gregory XV in Rome where his style began the transition from baroque to classical. The vigorous brushwork, saturated colors, and bold, naturalistic modeling of the figure of Jacob are hallmarks of this transitional period.

The composition of this work is unusual for Guercino. First, the work portrays, not a saint, but the biblical character, the mourning father Jacob. Second, only a single figure is rendered and not a scene of the biblical event, whereas most works illustrating this tragedy show Joseph’s brothers in addition to the patriarch. Because of these compositional choices, Guercino presents a moment in time for the observer to ponder the emotions of Jacob. As such, the work could be seen as an allusion to God the Father’s loss of His Son or as any parent’s loss of a child. Either way, the work is more devotional than historical.

But it is impossible to separate the figure from the story. The work’s primary impact is the pathos it generates in the viewer. Not only has Jacob lost his favorite son, but he becomes the victim of deceit, his lifelong characteristic. After deceiving his father, Jacob is deceived, in turn, by his father-in-law, who first marries him to Leah and later to Rachel whom he loves. Jacob favors Joseph, his eleventh son and elder of Rachel’s two sons, making him a coat of many colors. Their increased jealousy causes the brothers to sell Joseph into slavery and use the blood-stained coat to deceive their father into believing the teen was killed by wild beasts. A devastated Jacob looks to heaven. Is it to ask for God’s comfort or to ask God why He has brought evil into his life? Regardless, Jacob goes to the right source, though he receives no answer. Uncomforted, he declares, “I will go down into the grave unto my son mourning” (Gen 37:35).

The painting, however, does not match the biblical account. Rather than a vibrant cloak, Guercino’s white garment succeeds on both the literal and symbolic levels: the bloodstains which clinch the lie are clear evidence, and the color white (which indicates innocence) argues that Joseph has been unjustly treated by his brothers. However, God is at work. Ultimately, innocent Joseph is vindicated with the most powerful position in Egypt, second only to Pharoah, allowing him to save all of Jacob’s household during a prolonged famine.

This moving work, illustrating one of the most devasting losses a parent can experience, offers much to contemplate. But as with all proper devotional art, this work points the viewer to the God of all the earth who will do right. Bad things do happen to good people; this world is a vale of sorrows; and character flaws do bear fruit—but God guides the lives of His children, using even those “bad things” to work together for good.

Dr. Karen Rowe Jones, M&G board member

Published 2022