Scenes from The Annunciation: God the Father in a Glory of Angels, St. Gabriel the Archangel and The Virgin Annunciate

Oil on canvas

Francesco Montemezzano

Venetian, c.1540-after 1602

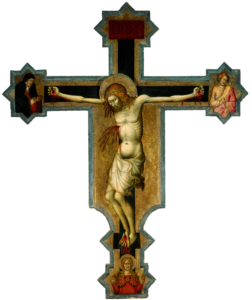

In museum collections, including the Museum & Gallery, there are paintings that were once part of a larger narrative, but now stand as individual works of art. These pieces, usually parts of large altarpieces, have been reduced in size for various reasons such as damage to the whole, for profit, or to fit a new arrangement. Very few that have been broken up have managed to stay together. Francesco Montemezzano’s The Annunciation is one of those lucky few.

At first glance in the galleries, you may notice a similar velvety color palette and free brushwork but may not realize they are one of a whole. If not for the close arrangement in display, one may not be able to see the full image. Originally in a horizontal format, the painting was altered sometime in the seventeenth century to fit a vertical, architectural enframement. Despite this physical cropping, we can still see the theme of the annunciation.

The annunciation is a common subject portrayed in Christian art. The moment is recorded in Luke 1:26-38 where Gabriel informs Mary that she will fulfill the prophecy of Isaiah 7:14 promising “a virgin shall conceive and bear a Son, and shall call His name Immanuel.” This theme became very popular in fifteenth-century altarpieces and were reinterpreted by artists throughout history such as Fra Angelico, Leonardo da Vinci, Botticelli, Caravaggio, Peter Paul Rubens, and John William Waterhouse. Each artist put their own spin on the theme, reflecting the stylistic ethos of the time and the artists’ own taste, but there are common elements.

Mary, Gabriel, and a dove are the main figures. Sometimes they are outside in an hortus conclusus or “enclosed garden,” and other times they are cloistered inside, symbolizing Mary’s chastity. Lilies are usually present, carried by Gabriel or somewhere in the composition, further emphasizing Mary’s purity as a virgin. Mary is commonly shown in prayer with a prayer book or missal kneeling at a prie-dieu. A dove or beam of light usually represents God’s blessing on Mary as His chosen handmaiden or the symbol of immaculate conception.

With this brief background, Montemezzano’s Annunciation stands out. We can see architectural elements throughout the three paintings and a possible garden behind Mary. Was this Montemezzano’s nod to the hortus conclusus? And where is the dove or beam of light that is often shown? Because of its fragmented state, we may never know exactly what the artist designed. However, Montemezzano did include one unique figure in this Annunciation—God the Father. Very few depictions of the annunciation include a physical God the Father, most only show his messenger Gabriel and the dove.

There are actually two other annunciation scenes in M&G’s collection that show God the Father in physical form (one found in galleries 4 and 10). Here, in Montemezzano’s work, God the Father is shown breaking through clouds and the architectural ceiling, symbolizing His passage into the earthly realm. Despite the unique inclusion of God the Father, His presence fits the annunciation theme perfectly. It is a foreshadowing of another part of the Trinity, Jesus, coming into our world to dwell with us as told by Matthew 1:23, “Behold, a virgin shall be with child, and shall bring forth a son, and they shall call his name Emmanuel, which being interpreted is, God with us.”

The Annunciation reminds us of promises fulfilled, how a Savior will dwell with us and come into this broken world to make us whole. While this painting will never have that opportunity to be truly whole again, we as believers are reminded of that promise for us this Christmas season.

KC Christmas Beach, M&G summer art educator

Published 2024