Object of the Month: July 2023

St. Barbara, St. Catherine, and St. Euphemia

Oil on panel

Unknown Rhenish School

Rhenish, active c. 1500

Although there is no biographical material on the painter of these works, we do know two facts. First, he was Rhenish (a designation coined in the 1300s referencing those who lived in a loosely defined region of Europe bordering the Rhine). Second, we know that he was active around 1500—at the height of the Renaissance. During his lifetime literacy and learning were increasing, capitalism emerging, scientific discoveries flourishing, and with the invention of Gutenberg’s printing press mass communication was transforming every aspect of European culture. In The Panorama of the Renaissance Margaret Aston notes, “The invention of printing changed the whole intellectual world forever. Without it, classical learning would have been confined to a Coterie of scholars; the reformation would have been a quarrel between theologians; popular literature would have been impossible; scientific discoveries would have languished unread” (p. 206).

This “revolution” had a tremendous influence on the visual arts as well. Artists across Europe could now readily disseminate images of their paintings, woodcuts, and engravings for critique and profit. In addition, printed versions of works like Jacobus de Voragine’s The Golden Legend reinvigorated the visual imagination. Originally compiled between 1260 and 1298, de Voragine’s hagiography (idealized biography of the saints) became the most printed book in Europe between 1470 and 1530. One 16th-century historian observed that “artists found in The Golden Legend a storehouse of events and persons to be illustrated,” and the imagery created in these “illustrations” helped codify the iconographic tradition we still reference today. For example, the figures in this panel painting are identified by their attributes—objects, clothing, colors, and symbols linked to their specific biographies. As we’ll see in our analysis, attributes may be shared by more than one saint; however, each saint usually has at least one key attribute that highlights his or her individuality.

Although St. Barbara, the first of the three saints in this panel, was one of the most popular saints during the Middle Ages, her story is most likely fictional. In Lives of the Saints, Alban Butler notes “There is considerable doubt of the existence of a virgin martyr called Barbara, and it is quite certain that her legend is spurious.” Regardless, her story is a fascinating read. According to legend, she was the beautiful daughter of Dioscorus—a wealthy Roman who built a lavish tower to hide her from the world. Dioscorus’s motivation for this sequestration varies. In some versions he is driven by protective love, in others simple cruelty. Details of her conversion also vary. In one of the more popular accounts, while her father is away on a journey Barbara invites a Christian disciple to visit her in the tower and is persuaded to accept Christianity. Soon after her conversion she summons a workman and insists that he create a third window in her tower wall. Upon his return, Dioscorus questions this architectural alteration. Barbara replies: “Three windows [symbolizing the trinity] lighten all the world and all creatures, but two make darkness.” She also reveals to her father her newfound faith. Enraged Dioscorus turns her over to the Roman authorities to be tortured. Then, at his own request, he is given a sword and “permitted to strike off her head.” But this cruel deed does not go unpunished. As Dioscorus travels home, he is struck down by a bolt of lightning and dies. In addition to the sword, Barbara’s key attributes include the sacramental cup and wafer pictured in M&G’s work and the three-windowed, cathedral-like tower shown in Jan van Eyck’s metalpoint brush drawing. The palm frond (which Romans used as a symbol of victory) is also included in van Eyck’s portrait and is a common symbol of a martyr’s triumph over death.

The sword held by the remaining two figures is also a commonly shared symbol of martyrdom by beheading. However, both figures are also pictured with an additional symbol unique to their individual narratives. Notice the broken, spiked “wheel” entwined in the hem of the central figure’s robe; this object identifies her as Catherine of Alexandria whose martyrdom involved not only a sword but also a spiked wheel. Dr. Karen Jones covers the details of this Egyptian princess’s life and iconography in an article highlighting another M&G portrait of Catherine by Francesco Casella.

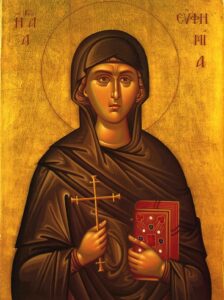

St. Euphemia is memorialized in both Catholic and Greek Orthodox hagiographic literature and art. The M&G image with its subtle blending of flesh tones and more complex figuration is characteristic of a western painting style, while the inset portrait to the right highlights the stylized form and painstaking precision of Greek icon painting. Both images, though vastly different, are equally compelling. Differences in the literary texts are minimal. In almost all versions, Euphemia is born in Chalcedon in 304 A. D. when Rome ruled the known world. height. The narrative begins when the Chalcedon governor Priscus orders all inhabitants to attend a festival honoring the god Ares. Unwilling to participate in this pagan ritual 49 believers (including the young Euphemia) gather in a house to pray. Their hiding place is soon discovered, and the worshipers brought before Priscus. For 19 days they are tortured but all refuse to deny the faith. So Priscus sends all but Euphemia to Emperor Diocletian in Rome for execution. Separated from her fellow believers, the governor tempts her with promises of earthly blessings; still Euphemia stands firm. Enraged the governor orders her cast into fire, but the flames fail to burn her; he then sends her into the arena, but the wild animals refuse to attack her. It is here in the climax of the narrative that Greek and Catholic versions of the legend diverge. In the Greek version Euphemia prays that the Lord will allow her to die a violent death in the arena. In answer to her prayer a she-bear approaches and gives her a small wound in the leg. Blood begins to flow from the wound and eventually she dies. In the Catholic version she is eventually beheaded for neither lions nor bears will do her harm. Hence, her distinguishing attribute is either a bear or a lion like the one languidly resting at her feet in our Rhenish panel.

This is one of two panels created by this unknown master. His second panel (equally lovely) showcases Saint Margaret, Saint Ursula, and Saint Agnus. We’ll take a look at their stories in our next month’s article.

Donnalynn Hess, Director of Education

Additional Resources:

The Golden Legend or Lives of the Saints. Compiled by Jacobus de Voragine, Archbishop of Genoa, 1275. First Edition Published 1470. Englished by William Caxton, First Edition 1483, Edited by F.S. Ellis, Temple Classics, 1900 (Reprinted 1922, 1931.)

One Hundred and One Saints: Their Lives and Likenesses Drawn from Butler’s “Lives of the Saints and Great Works of Western Art.” A Bulfinch Press Book: Little, Brown and Company (Compilation Copyright 1993).

Published 2023