If Raphael’s paintings reflect the philosophic concepts and artistic tastes that shaped the time, Leonardo’s life and work highlight technical innovations that would take western art to a whole new level.

Tag Archives: 15th century

Jan Gossaert, called Mabuse, was one of the first Netherlandish painters to integrate an Italian and Northern style. His beautiful Madonna of the Fireplace in one stunning example of his skill.

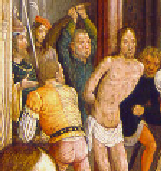

Watchers and Soldiers from a Crucifixion Group

Polychromed and gilt wood

Although the title Watchers and Soldiers from a Crucifixion Group seems insipid at first read, these two small polychromed and giltwood sculptures provide fascinating insights into an architectural style and installation of extreme magnitude. During the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, the Spanish monarchs who commissioned Columbus’ 1492 voyage to the Americas, the Isabelline style of architecture was developed. Born in France and trained in Flanders, Juan Guas settled in Toledo to establish his business. He is considered one of Spain’s finest architects and one of the key originators of the Isabelline style, which combines a Flemish-Gothic influence with Mudéjar (Spanish-Muslim) ornamentation. His design influence is represented in the monumental edifices at the San Juan de los Reyes and El Paular monasteries.

M&G’s two figural groups date to the second half of the 15th century and according to William Holmes Forsyth, the late curator emeritus of medieval art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “They are from a retable or retablo of Spanish origin, but southern Netherlandish in inspiration.” Beatrice Gilman Proske, the former research curator of sculpture at the Hispanic Society of New York who authored the catalog for the famed outdoor sculptures of Brookgreen Gardens, noted that they are Flemish. It is not then a stretch of scholarship to assume that these two sculptures measuring 32” high by approximately 15” wide, would have commanded a prominent place flanking the carved crucifixion of Christ, a common focal point in many retables from the Low Countries of the time. The Carved Retable of the Passion of Christ, part of the collection at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia, presents a prime example.

At the base of each carving’s scene amidst the jagged rock are bones resembling those from the lower torso and limbs of the human body. These skeletal remains add a sobering reminder that Roman crucifixion included the breaking of the leg bones in order to hasten the impending death. Moreover, the crucifixion of Jesus, as noted by all three synoptic Gospels, occurred on Golgotha or “the place of the skull.”

Positioned on these rocky formations, the Soldiers are each individualized by gaze and weaponry and robed in medieval armor and Moorish headdress, hinting at the Mudéjar influence. The sculptor clearly draws our attention to the only soldier gesturing and glancing upward, perhaps depicting the centurion cited in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and John. Church history, tradition, and pseudepigrapha all ascribe the name of Longinus to this legionnaire, but Scripture allows him to remain anonymous, recording for all time only his striking statements, “Truly this was the Son of God” (Matthew 27:54) and “Certainly this was a righteous man.” (Luke 23:47)

Unlike the soldiers, the Watchers from a Crucifixion Group can be decoded from Bible references, religious iconography, and an abundance of artistic renderings of those who attended Christ’s crucifixion. The repertoire is rich as set forth in examples such as El Greco’s Crucifixion, and Jan Van Eyck’s.

At center front Mary, the mother of Jesus, robed in blue (alluding to heaven, truth, and mourning) and white (for purity and innocence) is comforted by the obviously young apostle John draped in red (for love). On either side of him stand the two Marys, clearly identified in the crucifixion passage in John’s gospel as Mary the wife of Cleophas, and Mary Magdalene (recognized by her long hair as a penitent saint). In the background, towering above the rest of the group, is most likely Joseph of Arimathea, who provided the burial tomb for Christ; he is presented as elderly and robed in the costly garments of the rich. The sculptor carved this individual with an intriguing gesture. With his right index finger raised to his temple, perhaps Joseph is recalling the Scriptures he memorized while serving as a Sanhedrin senator attesting to the deity of Jesus, the Christ.

At center front Mary, the mother of Jesus, robed in blue (alluding to heaven, truth, and mourning) and white (for purity and innocence) is comforted by the obviously young apostle John draped in red (for love). On either side of him stand the two Marys, clearly identified in the crucifixion passage in John’s gospel as Mary the wife of Cleophas, and Mary Magdalene (recognized by her long hair as a penitent saint). In the background, towering above the rest of the group, is most likely Joseph of Arimathea, who provided the burial tomb for Christ; he is presented as elderly and robed in the costly garments of the rich. The sculptor carved this individual with an intriguing gesture. With his right index finger raised to his temple, perhaps Joseph is recalling the Scriptures he memorized while serving as a Sanhedrin senator attesting to the deity of Jesus, the Christ.

Bonnie Merkle, Docent and M&G Databases Manager

For further study:

Heaven’s Backdrop

Retro Tablum: The Origins and Role of the Altarpiece in the Liturgy

Making a Spanish Polychrome Sculpture, J. P. Getty Video

Published in 2019

Madonna and Child

Polychrome and Stucco, c. 1400s

Antonio Rossellino

Florentine, 1427-1479

Sculptor Antonio Rossellino was born into a family of masons—the youngest of five, talented sons and learning his craft from his older brother, Bernardo. Because of his hair color, Antonio earned the name, Rossellino, which means “little redhead.”

Antonio’s most famous work was completed in 1473 for the Burial Chapel of the Cardinal Prince Jacopo of Portugal found in San Miniato al Monte in Florence.

He worked with multiple artists to design and complete the Chapel including Luca Della Robbia, the distinguished terracotta sculptor and glazer. This remarkable collaboration of artists allowed creativity and beauty to spring forth figuratively and literally from stones and dirt.

M&G’s relief sculpture of Rossellino’s Madonna and Child is representative of a popular image that was painted, carved, and sculpted repeatedly during the Renaissance period. Image fatigue has not set in; we still find the subject appealing in the same way that we enjoy a sunset’s beauty night after night.

Studying the sculpture’s tabernacle frame, we notice the words: Ave, Gratia, and Plena. The translation of which is “Hail, Full of Grace”—a greeting perhaps at the entrance of the family home or private chapel. Below the inscription are carved three fleur-de-lis and the crossed fore-legs of the lion. More than likely, this relief was made for the Morelli family, a prominent family from Florence, whose coat of arms includes the crossed fore-legs of the lion. The fleur-de-lis is the symbol of Florence, originating in the medieval era.

Studying the sculpture’s tabernacle frame, we notice the words: Ave, Gratia, and Plena. The translation of which is “Hail, Full of Grace”—a greeting perhaps at the entrance of the family home or private chapel. Below the inscription are carved three fleur-de-lis and the crossed fore-legs of the lion. More than likely, this relief was made for the Morelli family, a prominent family from Florence, whose coat of arms includes the crossed fore-legs of the lion. The fleur-de-lis is the symbol of Florence, originating in the medieval era.

Both Mary and Christ are painted in their customary colors of red, blue, and white symbolizing love, faith, and purity. Mary’s fingers are delicately rendered in terracotta. Surrounding the mother and child are three, winged angel heads carved without bodies, possibly cherubim. Traditionally, angels were viewed as messengers and protectors of the righteous. How fitting for Rossellino to include angels in his portrayal of Christ considering Scripture’s promise in Psalm 91:10, 11, “For he shall command his angels concerning you to guard you in all your ways. On their hands they will bear you up, lest you strike your foot against the stone.”

Angie Snow, M&G Educator

Published in 2019

Cathedra

Walnut

Spanish, mid 15th century

A chair, from the English chaere or Latin cathedra, is one of the most common pieces of furniture and easily identified in its simplest form by its parts—back, seat, arms and legs. The chair’s specific purpose can be discerned by more descriptive names such as recliner, wheelchair, throne, etc. Of course, the person “who takes a seat” can further outline the chair’s scope such as the Queen of England positioned in The Chair in the House of Commons to open a new session of Parliament, a ruling monarch seated on a throne to make a solemn declaration, or a bishop (such as the Pope, known as the Bishop of Rome) adopting a position in a cathedra or cathedrae apostolorum (as it occurs in early church writings) to teach with apostolic authority.

The Museum & Gallery’s furniture collection from the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries is known as the most extensive representation in America and includes several types of ecclesiastical chairs, four of which are cathedrae. Each of the four has interesting designs and carvings, but the oldest in the collection possesses by far the most intriguing and traceable features.

Gazing from the back panel of the Cathedra is a sculpted female figure representing St. Lucy, one of the most venerated female saints in martyrology and mentioned in the Catholic mass itself. She holds two objects: a palm frond, symbolic of victory in death and a platter with eyes, her most common and legendary attribute.

Just under the seat panel is a misericord. Since many of the medieval and early Renaissance ceremonial prayers were uttered in a standing position, the misericord acted as a place to “rest” or lean on during the long ceremony thereby allowing the bishop to obtain a type of “mercy.”

This Spanish Cathedra dates with certainty to the 1400s due mostly to the identifiable coat of arms of Bishop Alonso de Burgos, born in 1415 in Burgos, Spain, the capital of Old Castile. The galero or pilgrim’s hat and tassels were common elements of the crest of a bishop, with the center shield denoting a particular symbol of heritage or character, in this case a lily in the stylized form of a fleur-de-lis, which is a symbol of purity. Alonso’s influence as a bishop was widespread as he served in the central Spain dioceses of Cordoba, Cuenca, and Palencia. Ordained as a Dominican monk at an early age, Alonso so earnestly and diligently applied himself to his vocation as a Catholic clergyman that he was readily noticed and subsequently assigned as confessor by the renowned Catholic Monarchs, a collective term for Spanish King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I, under whose banner Columbus sailed.

This Spanish Cathedra dates with certainty to the 1400s due mostly to the identifiable coat of arms of Bishop Alonso de Burgos, born in 1415 in Burgos, Spain, the capital of Old Castile. The galero or pilgrim’s hat and tassels were common elements of the crest of a bishop, with the center shield denoting a particular symbol of heritage or character, in this case a lily in the stylized form of a fleur-de-lis, which is a symbol of purity. Alonso’s influence as a bishop was widespread as he served in the central Spain dioceses of Cordoba, Cuenca, and Palencia. Ordained as a Dominican monk at an early age, Alonso so earnestly and diligently applied himself to his vocation as a Catholic clergyman that he was readily noticed and subsequently assigned as confessor by the renowned Catholic Monarchs, a collective term for Spanish King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I, under whose banner Columbus sailed.

Beyond being instrumental in the financing of some of the voyages of the discoverer, Bishop Alonso’s influence was exhibited in founding a center for Dominican study, the Collegio de San Gregorio, an Isabelline-style building located in the city of Valladolid. Readily visible throughout the architecture is Alonso’s heraldry.

Beyond being instrumental in the financing of some of the voyages of the discoverer, Bishop Alonso’s influence was exhibited in founding a center for Dominican study, the Collegio de San Gregorio, an Isabelline-style building located in the city of Valladolid. Readily visible throughout the architecture is Alonso’s heraldry.

Bonnie Merkle, M&G Docent and Database Manager

Published in 2019

Angel with Candlestick (pair)

Polychrome and parcel-gilt

Unknown

Florentine, c. late 15th century

Since paintings in an exhibit often take “center stage,” ecclesiastical pieces like these Angels with Candlestick can be overlooked by museum viewers. During the Renaissance, however, a polychrome sculptural grouping would often be the centerpiece of an altar’s decorative scheme while the painted narrative scenes or figures functioned as the “wings” of the altar. Although by the end of the sixteenth century, paintings became the central focus of Italian altarpieces, while sculpture continued to be used extensively in other countries like Spain.

The term polychrome (meaning “many colored”) refers to the application of colored materials to sculpture in order to present a more life-like quality. This technique dates back to the Greeks and Romans and was particularly popular during the Renaissance. Because these pigments fade over time such coloring is rarely discernable today. The good condition of these statues is due to the porous wood used which retains color well.

We know that the figures shown here were meant to be angels from the metal pins that remain on the back of each figure—a clear indication of the wings’ placement. Sadly, it is not uncommon for such appendages to be broken off or lost over centuries of movement from place to place. Fortunately, the carved wooden haloes have remained intact, as has the original base with its Latin inscriptions.

Since several of the words are Latin abbreviations, the precise translation of the inscriptions is unclear. However, a loose reading would be:

OVEM DEDIT VOBIS DNS ADVES CENTVIM

Dedicated to the Lord’s Advent

VENITE ET COMEDITE PANEM

Come and eat bread

ANGE ORVM

Angels

Donnalynn Hess, Director of Education

Published in 2018

Christ before Pilate

Oil on panel

Master of St. Severin

German, active c. 1485–1515

Click on the links throughout the article to view additional artists’ works and reference material.

Little background history exists for the artist referred to as the Master of St. Severin. While scholars remain uncertain as to his identity, they have confidently identified a body of works they believe to be by his hand. The Church of St. Severin houses what are considered his best works, thus he became known by the pseudonym, the Master of St. Severin. His body of work primarily reflects oil paintings on panel, however, there is some indication that he might have also designed and produced stained glass windows.

Christ before Pilate brings together several of the events of the Passion Week leading to the crucifixion of Christ. He did a similar work called Passion Scene: Christ at the Mount of Olives. Both works embody his style evidenced in the stiffness of the figures and the similarity in facial features and expressions of all figures. In the foreground of M&G’s work, a solemn and calm Christ appears before Pilate for trial. The surrounding miniature scenes reveal the events preceding and following his trial. To the left in the distant background, the artist portrays Christ’s prayer and arrest in the Garden of Gethsemane along with Peter cutting off Malchus’ ear. Centrally located in the background and enclosed in a cathedral-like structure, Christ receives beating with the cat of nine tails and then just below He is crowned with a ring of thorns. Finally, to the far back right, Pilate presents Christ to the Jews.

Beautifully detailed in oil, the painting provides a window into the culture of the artist. Click the dropdown below to learn more about the clothing featured by the Master of St. Severin.

Dagging is cutting the edges of garments, hangi ng sleeve flaps, or even hats into pointed or squared scallops. This trend was especially popular during the late Middle Ages. The man in red at Christ’s crowning with thorns features dagging at the bottom of his doublet (jacket).

ng sleeve flaps, or even hats into pointed or squared scallops. This trend was especially popular during the late Middle Ages. The man in red at Christ’s crowning with thorns features dagging at the bottom of his doublet (jacket).

Also known as crakowes, these were an elongated, exaggeratedly pointed-toed shoe often worn by nobles or the wealthy. King Edward III  tried to take matters into his own hands by declaring a law that “no Knight under the estate of a lord, esquire or gentleman, nor any other person, shall wear any shoes or boots having spikes or points exceeding the length of two inches, under the forfeiture of forty pence.” The law was ineffective, and the trend lasted until 1480! The man, at right foreground and near to Pilate, models poulaines.

tried to take matters into his own hands by declaring a law that “no Knight under the estate of a lord, esquire or gentleman, nor any other person, shall wear any shoes or boots having spikes or points exceeding the length of two inches, under the forfeiture of forty pence.” The law was ineffective, and the trend lasted until 1480! The man, at right foreground and near to Pilate, models poulaines.

These were a special non-functional, decorative sleeve attached to the jacket; in the early Renaissance, they were mostly us ed for ceremonial occasions as seen here on the soldier kneeling in the foreground.

ed for ceremonial occasions as seen here on the soldier kneeling in the foreground.

Parti-colored is the sewing together sections of different colored fabrics within the same garment. This was used in both men’s and women’s clothing and could reflect the colors of a particular city or families joined in marriage. The man kneeling in front of Christ at his crowning with t horns features

horns features a parti-colored doublet. At the beating of Christ, the man to the left of Christ also wears a parti-colored doublet.

a parti-colored doublet. At the beating of Christ, the man to the left of Christ also wears a parti-colored doublet.

Rebekah Cobb, Guest Relations Manager

Published in 2017

Mille-Fleurs Tapestry

Franco-Flemish, c. 1480

Gift of Z.E. Marguerite Pick in memory of Misty

Click on the links throughout the article to view additional artists’ works and reference material.

Mille fleurs tapestries are those with a myriad of small flowering plants sprinkled across a dark blue or red or sometimes dark brown background. Mille-fleurs is French, literally translated “thousand flowers.”

Tapestries have been around for centuries, and their use was not merely decorative as we might assume in today’s culture. These incredible textiles are constructed from a considerable amount of wool threads with varying amounts of silk, silver, and gilt yarns for beauty and richness. Their size and material provided insulation in the drafty, cold interiors of medieval castles and homes, and they could easily be rolled or folded and transported, which was a great advantage to those living back then.

However, the subject matter of tapestries varied significantly focusing on scenes from history, allegory, mythology, Scripture, and romance with coats of arms and decorative elements included too. The mille fleurs decoration, however, wasn’t necessarily linked to any specific subject, but sometimes might be; instead, as one writer describes, the flowering background is more of “an expression of the universal human love of fresh flowers and the wish to have bouquets of fields of them covering the walls”—especially in the barren winter months.

Although as symbols, mille fleurs particularly lend themselves to allegorical and romantic themes “furnishing a slight subject for tapestries entirely sprinkled over with sprightly growing plants” with the “now and then active dogs, strange beasts or an occasional human figure [who] claimed a space.”

M&G’s tapestry certainly meets this composition depicting the imaginary animal, the unicorn, with various birds (perhaps a falcon on the right) against the mille-fleurs background. The upper portion reveals a landscape of mountains and hills with tall grasses, trees, various buildings, towers, and castles—including one with a moat full of wavy, active water.

The unicorn has quite a history—through second-hand accounts, of course. This mysterious animal is described in classical references as having goat-like features, hence the cloven hooves and beard; he hunts in the mountains and is a very strong, fast animal that no one could capture. He is depicted on cylinder seals as far back as Babylon and Assyria and referenced in the fifth-century Greek writings by Artaxerxes’ physician, Ctesias. Other references of the unicorn appear in the old bestiaries.

Philippe de Montebello, former director at the MET, explains the interest in animals both real and imagined, “During the Christian era, the expressive power of animals perhaps reached its height in the Latin bestiaries of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. These books, labored over by the monks who copied them over and over again, combined factual, realistic observations of animal life with legend and served as allegorical texts for teaching clergy and laymen alike. Animals in their amazing diversity yielded illustrations and promulgations of desired behavior as well as warnings against misbehavior or evil.”

Of all the beasts, the unicorn (sometimes called the Monoceros) has become legendary. He symbolizes purity, and since the unicorn could only be captured by a virgin because of his attraction to her love of chastity, the hunt for the unicorn became an allegory of the incarnation of Christ as well as an allegory of romance and marriage. Thus, the unicorn appears in both secular and religious art—even on some vestments worn by priests.

It is said that the horn of the unicorn possessed the virtue of detecting poison as well as the power to render the poison harmless. According to legend the animals of the forest would not drink from a pool until the unicorn had first purified it with his horn. This story is depicted in one of the great unicorn tapestries in the collection at the Cloisters in New York.

The unicorn is often depicted in a place of colorful and abundant fauna, referencing Paradise—sometimes in connection with scenes of Creation and the Fall. He usually stands in the middle or off to the edge, alone or distant from the other animals, and sometimes near a body of water, perhaps immersing his horn.

For the gardeners and lovers of flowers, some of the plants possibly depicted include: foxglove, day lilies, rowan, and the daffodil. Look closely to identify these symbolic plants:

- Cuckoo Flower, which Pliny claims can repel snakes and “drive away melancholy and makes people happy in their hearts.”

- Blue Bell blossoms, which supposedly when a bluebell is suspended above the threshold, “all evil things will flee therefrom.”

- Wild Pansy, a symbol of remembrance and meditation

- English Daisies, which signify the joy of Easter, and in medieval Germany these were called massliebe or “measure of love” suggesting that even then girls plucked the petals saying, “He loves me, he loves me not.”

Without knowing more about the designer, weavers and past owners, it’s difficult to know the intention of the tapestry; however, its symbolism provides insight for both the secular and spiritual just as it did in its original home. The concept of appreciating nature and learning from our observation of it wasn’t new in the old bestiaries or even Aesop’s fables. King Solomon, the wisest man to ever live, exhorts the reader in his wisdom writings of Proverbs and Ecclesiastes to observe God’s creation and find its parallels for application and improvement in our own daily living—a good start for a New Year.

Erin R. Jones, Executive Director

Published in 2017

Casket

Bovine Bone

Flanders, 15th century

Acquired with funds from the Audrey Love Charitable Foundation

Click on the links throughout the article to view additional artists’ works and reference material.

Special boxes or caskets were once made to hold valuable items or at least the personal items of the wealthy. These containers, used for storage and transport, are often beautifully decorated and constructed of rich materials themselves—a practice that has existed for centuries as far back as Egyptian culture.

Many of the surviving caskets focus on romance—decorated with scenes from medieval literature including Tristan, Taking the Castle of Love, Aristotle’s infatuation with Phyllis, poems by Homer, and the concept of chivalry in the characters of Sir Gawain, Lancelot, Percival and others. Thomas T. Hoopes, former curator at the MET explained, “In nearly every case they are decorated with scenes from popular legend and romance, especially with such as would have an allegorical significance appropriate to the occasion for which they were designed.”

In the middle ages, France was the primary creator and market for the luxury items of carved ivory and bone, but by the fifteenth century the center of industry shifted. The best known craftsmen were the and Florence. For four decades, this group of artisans created and satisfied the demands of fashion crafting beautiful objects in ivory, wood, bone, and horn. The workshop produced a variety of carvings including large and small altarpieces, but their principal output seemed to focus on special, personal items such as caskets, mirror cases, and small toilet articles—many of them bridal gifts or gift sets for the wealthy and noble of the court.

However, the Embriachi weren’t the only entrepreneurs in carving; the industrious and creative Dutch also continued the French tradition. The workshops in both the southern and northern Netherlands innovated and developed commercial centers for a variety of products including textiles, metalwork, and oil painting. Specifically, the workshops in Flanders developed an export trade of bone boxes and ivory products that traversed the Rhine river routes to European cities and markets—bone boxes like the present Casket.

M&G displays a number of cassone and chests used by our European forbears to store their household items as well as a few smaller versions of storage containers in the form of coffers and now a casket for protecting one’s precious personal items: jewelry, documents, and sentimental objects.

At one time, it was the height of medieval fashion to own a casket, but with the delicate nature of the material it is unusual to have an intact box that has survived time, use, and past repairs.

The Casket is constructed of bovine bone mounted on a wood structure. The bottom of the box is a checkerboard pattern of wood and bone, and the sides and top are carved in low relief, which still retain some gilding and color. The carved decoration is religious depicting Christ, apostles such as Peter holding the keys, and various saints including St. Catherine identified by her wheel. Perhaps the religious decoration on its exterior reveals that this Casket formerly sheltered a manuscript or religious text.

Since the background of the individual bone plaques is crosshatched, it may indicate that the workshop was influenced by religious prints and engravings from the time period, such as Biblia Pauperum (the Pauper’s Bible).

While the interior is lined by worn and repaired green fabric, interestingly, what was so valued to be safely stored inside is now lost. Once an expensive, beautiful container for holding something of great value, however, it is now the container itself that has become the treasure.

M&G is grateful for the generosity of the Audrey Love Charitable Foundation, without whom we could not have acquired this beautiful, mysterious medieval object.

Erin R. Jones, Executive Director

Published in 2016