The Fountain of Life

Potmetal and stained glass

Unknown

French, 16th century

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Walter W. Lee

Every collection object has a life story to tell, and the fascinating narrative of these beautiful windows begins in the fertile flood plain of the Loire Valley in France, near Saumur…

The Windows’ Story

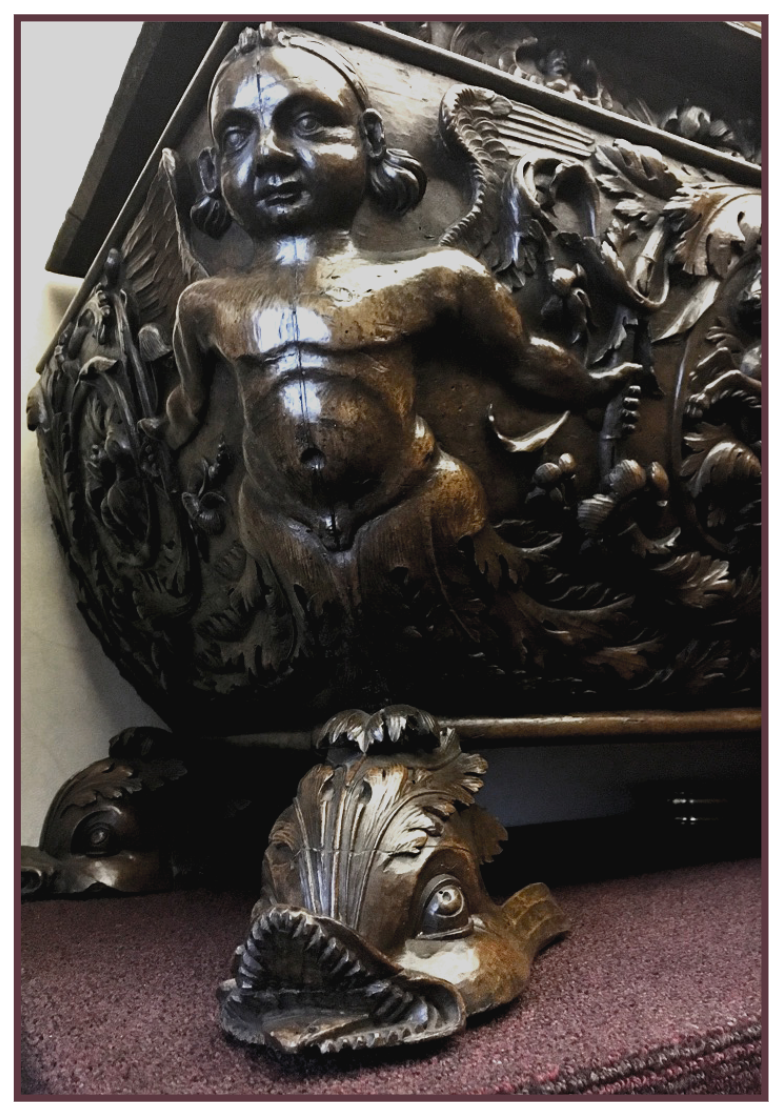

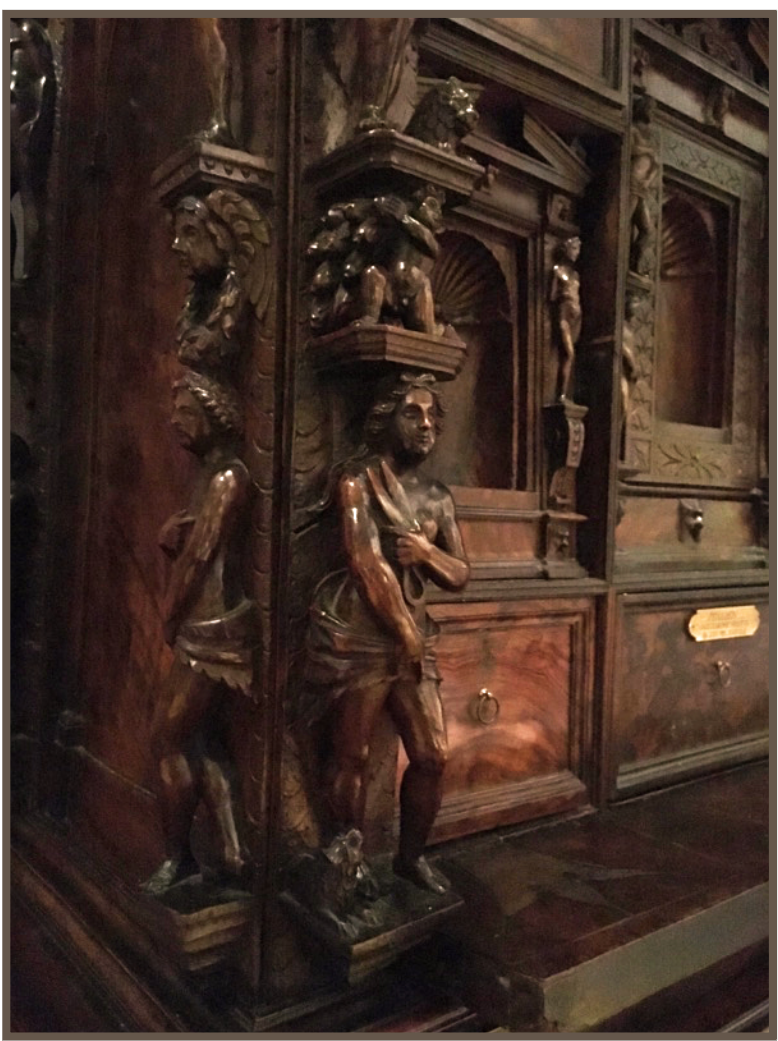

At his mother’s passing, Baron René de Thory inherited estate and lands as the new Lord of Boumois. His wealth included the ruins of a castle once owned by the Counts of Anjou and which was destroyed during the Hundred Years War. Following his marriage to Françoise du Plessis, René undertook the building of Chateau Boumois between 1521 and 1525 on the remains of the former Angevine castle.

The chateau’s designs included private living quarters, guest areas, public entertaining areas, kitchen, bakehouse, pantry, cellar, and towers. As is fitting the role of the Lord of Boumois who held a seat of authority, the house included a dungeon and space for hearing judicial cases. To run such a household required servants, their living quarters, stables, a courtyard, and a dovecote. Since the area was a central hub for the activity of those living and working on the estate, there was a chapel for worship; and all at the castle were protected by a surrounding moat.

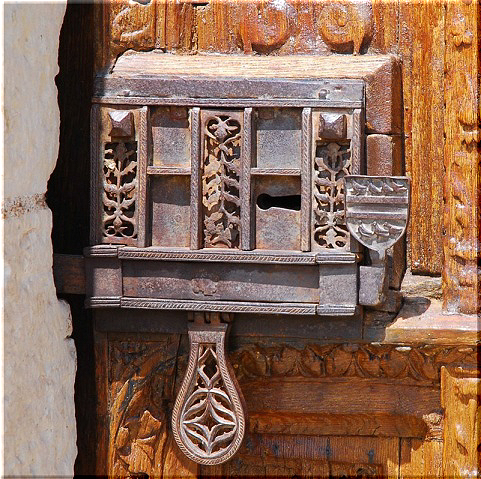

In Anjou, there are some 1200 castles remaining today; Boumois is classified as a French Historical Monument and is one of the last remaining castles of Gothic architecture. Christian Cussonneau writes, “Boumois still offers today despite some mutilations, the essential features of a manor house at the end of the Middle Ages.” On a beautiful imposing, carved door at the chateau, there still remains the de Tory coat of arms on the lock (see image).

The chateau’s chapel was completed by 1525. To appropriately beautify the space, René de Thory commissioned stained glass windows, which were most likely created and installed before his wife, Françoise du Plessis, passed away in 1528/9. The chapel windows consisted of three sections:

- The central window of three panels: the Fountain of Life

- On the West wall: two lancets featuring the donor, René de Thory, presented by St. René to the Virgin of Pity (also known as the Pieta). De Thory is depicted as a kneeling knight wearing his family coat of arms; the window includes the Latin inscription: Omniae dei memoria mei meaning “Remembering that all things are for God.”

- On the East wall: two lancets featuring Françoise du Plessis presented by St. Francis of Assisi to the Virgin and Child with saints (most likely including St. Barbara, the patroness of the daughter of Lord and Lady Boumois). These panels have since disappeared and are known only from written sources from the nineteenth century and supposedly by a photograph taken around 1890.

Not long after his wife’s death, René de Thory fell in love with Anne d’Assé, wife of François de Villeprouvée, Baron of Trier, who died under suspicious circumstances in January 1530. Questions arose that perhaps Anne’s husband was poisoned. Since poems written by René about his love for Anne were discovered, the two were accused and tried for murder; however, they were not convicted and secretly married in March 1530.

While the windows of the chapel honor the first Lady of Boumois, de Thory had the chapel consecrated as the Chapel of St. Anne by the priest at Saint-Martin-de-la-Place on March 15, 1546 in honor of his second wife, Anne. At René de Thory’s death in 1565, Boumois was left to his wife and his son, Antoine de Thory.

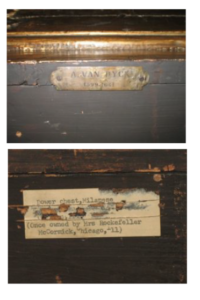

The estate stayed in the de Thory family until sold in 1607, and then changed owners repeatedly over the next 300 years including a sale of the chateau’s furnishings in 1833. At the end of the nineteenth century, the architect and designer Stanford White obtained the five stained glass panels. He was known for decorating in the neo-Gothic style favored by his wealthy clientele—the nouveau riche seeking to create the wealth of the Old World in their American homes. After White’s death, newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst acquired the panels in 1907. Later, through a gift purchased by Mr. and Mrs. Walter Lee from French & Co, M&G received the windows in 1956.

The Windows’ Imagery

Stained glass as an art reached its peak in the Middle Ages; the cathedrals with the increased buttressing allowed for more windows, whose colored beams of light created beautiful effects in the sanctuary by illuminating the space and using light to “paint” the Scriptural stories. Jacques DuPont explains “this form of painting is less an ornament than the lyrical expression of a transcendent world” as stained glass creates “an atmosphere befitting the House of God, the Light of the World.”

Having a complete set of windows from this period is rare, and the imagery of the central windows is dramatic. In this crucifixion scene, the cross bearing Christ’s suffering body with five bleeding wounds stands above a fountain in which Adam and Eve are bathing—being cleansed of their sin; Christ’s blood then flows into a larger pool representing the forgiveness provided for all mankind—“whosoever will” may be cleansed and made righteous through faith in Christ’s sacrifice. Above Christ is a door perhaps referencing Christ’s own words, “I am the door…. I am the way, the truth, and the life; no man cometh unto the Father, but by me.”

Interestingly, the four fountain heads are the symbols in art for the four evangelists: an angel (Matthew), a lion (Mark), an ox (Luke), and an eagle (John). The designer may have referenced the iconography of paintings in the region like the Fountain of Life at the Calvet Museum in Avingnon or a slightly different version at Saint Mexme in Chinon. Emile Male in his book Religious Art in France explains the symbolism of the four fountain heads, “This is an ingenious way of saying that the miracle of forgiveness has the Gospels as authority, that is to say, the Word of God Himself.” These windows present a beautiful representation of several doctrinal truths, such as the love of Christ, the power of His sacrifice to cleanse sin, and the fulfillment of His promise to Adam and Eve.

William Cowper, eighteenth-century poet, captured the same visual truth through language: There is a fountain filled with blood drawn from Emmanuel’s veins; and sinners plunged beneath that flood lose all their guilty stains.

Erin R. Jones, Executive Director

Published in 2018