The Triumph of David

Oil on canvas, c. 1630s

Jacopo Vignali

Florentine, 1592-1664

Italian art scholar Howard Hibbard once observed, “Florentine seventeenth-century art has a fascination and beauty worthy of our attention: it is a sensuously colorful and romantic school of painting, sometimes even magical or mystical.” The Museum & Gallery’s Triumph of David by Jacopo Vignali is a case in point. Described as one the most “poetic and sensitive” of the Florentine painters, Vignali began his career at 13 under the tutelage of Matteo Rosselli. In his early twenties he joined several other noteworthy artists in the decoration of the Casa Buonarotti—the most important commission in Florence at that time. By his early thirties, he was not only a member of the Academy but also one of the leading artists in Florence.

Rosselli’s superb tutelage provided Vignali with the technical and artistic skills necessary for his later success. However, as Vignali’s style matured, he became more eclectic, incorporating Counter-Mannerism with the grandeur, drama, and emotional intensity of the emerging Baroque aesthetic. This diversity is clearly apparent in The Triumph of David.

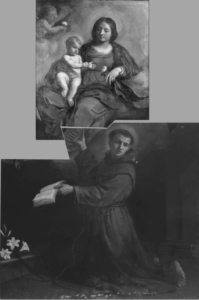

Seventeenth-century paintings on the life of David had been prevalent since the 15th century when the innovative, stunning sculptures of Donatello, Verrocchio, and later Michelangelo elevated this biblical figure into a civic symbol. Interestingly, our M&G painting was originally attributed to Vignali’s teacher Rosselli. Joan Nissman notes: “The answer to this problem of attribution, as Del Bravo suggests, seems to be that it is an early work painted while Vignali was still under the influence of his master. Vignali, in this painting, shares his master’s solid and smooth technique as well as his concern for details of costume.” However, a comparison of Rosselli’s treatment of the subject [fig. 1] with Vignali’s highlights why Carlo del Bravo’s attribution of the work to Vignali (rather than Rosselli) has now won general acceptance.

Notice that in Rosselli’s rendering we see the coloration, composition, and scale indicative of the classical Baroque style popularized by the Carracci. In contrast, Vignali’s more dynamic composition, vivid coloration, and careful use of scale reflect his mature style which favored the integration of Counter-Mannerist techniques with the dramatic realism of Baroque naturalism. For example, High Mannerist paintings were often characterized by strained poses, distortion of the human form, crowded compositions, garish coloration, and unusual (sometimes bizarre) elements of scale.

In this scene, however, Vignali manipulates these common characteristics to create a “restrained” but equally dramatic effect. For example, the composition is “crowded” but the poses elegant, the figures without distortion. The coloration is vivid but not garish, carefully integrated to create focus and highlight the triumphant mood of the scene (e.g., David’s bright red stockings draw the eye to Goliath’s head while the bright red sleeves of the woman’s costume create an implied horizontal line that guides the viewer’s eye back to the hero’s face).

Vignali also carefully manipulates scale. The extreme elongation of the sword and the enormous head of Goliath subtly serve to reinforce the power of the biblical narrative. Scripture notes that Goliath was about 9 feet tall, and although we are not told specifically how much his sword weighed, we do know that the head of his spear weighed about 15 pounds! In addition, the soft modeling of the faces, the contemporary dress, and the morbidly gruesome severed head highlight Baroque naturalism’s penchant not just for realism but also for the “bizarre and strident” (David Steel).

Although Vignali’s contributions to the early Baroque period are significant, he remains less well-known than either his teacher Matteo Rosselli or his most famous student Carlo Dolci. Joan Nissman attributes this lack of name recognition to the fact that, unlike Roselli and Dolci, the great seventeenth-century Florentine biographer, Filippo Baldinucci, did not write of Vignali’s life. Regardless, this work has long been praised as one of the finest treatments of The Triumph of David ever produced.

Donnalynn Hess, Director of Education

Works Cited:

Steel, David, Baroque Paintings from the Bob Jones University Collection. North Carolina Museum of Art.1984.

Hibbard, Howard and Nissman, Joan, Florentine Baroque Art from American Collections. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1969.

Published 2025