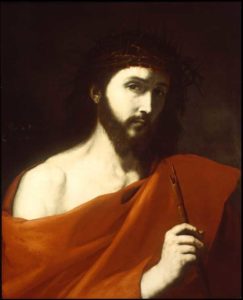

A Sibyl

Oil on canvas

Ginevra Cantofoli

Bolognese, 1618-1672

Click on the links throughout the article to view additional artists’ works and reference material.

From the Middle Ages to the early Renaissance, an artist’s instruction commonly occurred in the workshop of master painters or religious orders; however, in the 13th century, the craft guild system launched an apprenticeship program to carefully regulate the training, materials, and assessment of prescribed artistic techniques. The standard training began for boys (around 13 years of age) within a master’s workshop setting, which lasted 3-7 years; this process became the required expectation as outlined in Cennino Cennini’s, The Craftsman’s Handbook, a how-to-guide to artistic techniques, “If you do not see some practice under some master, you will never amount to anything, nor will you ever be able to hold your head up in the company of masters.”

Once completing the basic preparatory skills, the youth could progress to “journeyman” (a master’s assistant) by possibly journeying to another city to study and practice under a different master at a new level of training and collaboration. After 3-4 years (sometimes longer), he was allowed to submit a test piece to be evaluated by both his own master and other guild representatives. If his “masterpiece” passed, he would then be able to work as a “master” painter himself and acquire a permit to establish his own workshop and apprentices—hence the name, Old Master painters.

During the Renaissance, a new concept of artistic training developed known as The Academy—a private, informal instruction venue that not only developed artistic skill, but also included life observation, philosophy, and discussion to increase knowledge and broaden understanding.

These various methods of training were challenging for artists, but produced some well-known greats as well as some very gifted lesser known artists. While art education was well framed, suited to males, and even strictly regulated in areas, there were yet some options for a female to pursue training and have a presence in the world of art. One historian states, “Although there were routes to follow for a man who wanted to be an artist and no map at all for a woman, art training was more flexible than it seemed on the surface.” Even when excluded from apprenticeships and academies, history provides many examples of women that received artistic training through private tuition or lessons (if her family had money), from an artist-father in his workshop, in a convent, or from seeking out friendly advice.

Interestingly, a number of the known female painters spring from Bologna, Italy in particular. It was a city where women outnumbered the men and a place that prided itself for its famous university which as early as the 13th century opened its doors to women (some of whom became lecturers renowned for their scholarship).

Elisabetta Sirani, grew up in Bologna and under the tutelage of her artist-father, Giovanni Andrea Sirani, who (somewhat reluctantly) trained her in the manner of his master, the “Divine Guido” Reni. She became a respected painter and received important commissions for churches and portraits. She became a member of “merit” as a full professor and a member of “honor” of the Academy of St. Luke in Rome—one of the first women painters and the only Bolognese of her generation to enjoy this privilege. Since she was officially recognized as a professional artist, she could direct her own studio, take on apprentices, and train young artists. Breaking the tradition based on the model of arts education for men and women, Sirani welcomed women of all ages and backgrounds in her atelier including amateurs and aspiring artists like Ginevra Cantofoli, who went on to make a reputation of her own.

Ginevra Cantofoli is believed to come from a well-to-do family and was older than her teacher; yet, she was one of Elisabetta’s favorites and possibly became one of her assistants. She based many of her works on her teacher’s, and subsequently, some of her works have been confused as Sirani’s. However, she also produced original works including those for the Foresti family chapel and other large scale compositions for churches in Bologna. Rare for the 17th century, she earned her living as a professional artist; this is confirmed by a legal document drafted by the artist herself in 1688 in which reference is made to “money by her earned by her work of painting.”

A sibyl in classical mythology is a female prophetess often pictured with a book or scroll and which symbolized the harmony between Christian and Classical ideals. However, this work is unusual as a self-portrait of Ginevra who blends the classical sibyl and Hebrew prophetess. By painting a sibyl, she associated herself with areas where women had little influence during the time, such as ancient literature and languages and religious painting.

Based on history and the great numbers of male Old Masters that followed the accepted training processes, it is unusual to see works by female Old Masters; however if you visit M&G, you can see at least two examples on display in the collection including this unique self-portrait.

Erin R. Jones, Executive Director

Published in 2014