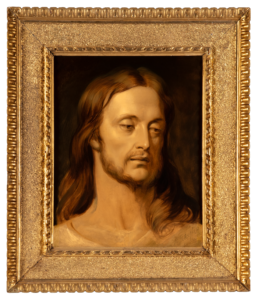

Head of Christ

Oil on panel, signed and dated lower right: A Scheffer 1849

Ary Scheffer

Dutch, active in France, 1795-1858

Ary Scheffer first studied art with his parents, later studying at the Amsterdam Drawing Academy. When his father died, Scheffer moved with his family to study in Paris with the neoclassical painter Pierre Guerin which set Scheffer on the road to Romanticism. A year later, he debuted at the Royal Academy’s Salon Exhibition. Five years after the move, he won his first medal which garnered him patronage by a supporter of the royal family.

The French would call this work an étude—a study made of a model to reference and work out details for a later painting. As such, collectors consider them valuable works. A glance at his oeuvre (body of work) reveals that Scheffer uses this model repeatedly for the Christ figure in several of his works largely during his religious period at the end of his career. Dated 1849, M&G’s study likely influenced later works, such as The Temptation of Christ (1854) in the National Gallery of Victoria and perhaps Christ Weeping over Jerusalem (1849) in the Victoria & Albert Museum (which he repeated in an 1851 version at the Walters Art Museum).

Scheffer’s popularity did extend to England but with a marked division in how the British received his works. The members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, just at the start of their own movement (1848), varied in their reactions: William Holman Hunt did not approve, unlike Thomas Woolner. In fact, Hunt convinced D.G. Rossetti that Scheffer’s works were “worthless” (Morris 180).

The Royal Academy in London criticized nearly all the technical aspects of his work, especially his coloring, possibly feeling vulnerable from the acclaim that he was receiving in the industrial North. The growth in the middle class through textile factories in cities such as Manchester and Liverpool made art collecting a mark of affluence and social status. These “barons” were already comfortable with Europe due to product exportation; the importation of ideas from there was a natural consequence. Scheffer was championed by the author Elizabeth Gaskell and collected by the “intensely pious John Heugh” (Morris 186). John Ruskin called him “one of the heads of the mud sentiment school,” but admitted that Scheffer “does draw and feel very beautifully and deeply” (Morris 180).

So if technical excellence was not the draw, what was? Edward Morris states that “it was above all spiritual and emotional exaltation particularly in expression that Scheffer’s English friends admired in his art” (176). This Head of Christ evidences the coloring that drew criticism: the palette is limited to creams and browns with little distinction between Christ’s clothing and His skin. But Christ’s face is what draws attention. Kindness, introspection, firmness of purpose, along with a far-seeing gaze, create the impression that the God-man is on an eternal mission. “Emotional idealism” can easily cross the line into sentimentality, especially in religious works. However, the appeal to sentiment often leads to contemplation, a result that all artists desire. And anything more than a passing glance at Scheffer’s Head of Christ compels the viewer to ponder the Savior of the world.

Dr. Karen Rowe Jones, M&G board member

Work Cited:

Morris, Edward. French Art in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Yale UP, New Haven. 2005