In this moving work we see combined two of Rembrandt’s favorite subjects: portraiture and biblical history.

Tag Archives: Dutch art

The story behind the acquisition of a work is often as fascinating as the story within the frame.

Esther Accusing Haman, considered one of Victor’s finest works, also gives us a fascinating look at actual samples of 17th-century table settings.

Christ and the Samaritan Woman

Oil on canvas, c. 1620

Abraham Bloemaert

Dutch, 1566-1651

Abraham Bloemaert, whose career spanned more than 50 years, adapted to several major changes in prevailing artistic styles. His art began firmly rooted in the late mannerist tradition with its elongated figure-types and complex compositions, but later changed to the tenebrist style brought from Italy by some of his students. As the master of many important Dutch painters, including Terbrugghen, van Bijlert, and Honthorst, Bloemaert is considered one of the most important and influential Dutch artists of the early 17th century.

The subject of Christ and the Samaritan Woman enjoyed popularity for many generations in the Netherlands. While artists generally painted this theme in a landscape (horizontal) orientation, Bloemaert chose a vertical one. This change allows him to focus on the figures in the foreground without surrounding countryside to distract the viewer. It also allows him to create a more intimate portrait of the two major characters in the story.

According to Art Daily, “The bulk of his painted oeuvre is made up of history pieces, paintings with large figures depicting an episode from a story. . . . Since the fifteenth century, art theorists had regarded history painting as the apex of the hierarchy of painterly genres.” And since this is a history painting, “to comprehend such a picture, [viewers] have to know the story” (Art Daily). Bloemaert portrays the Samaritan woman’s conversion as told in the Gospel of John, chapter 4. Of course, he needs to choose which moment in the storyline to freeze for the viewer’s consideration. But make no mistake, the whole story is important.

The Story

In John 4, a weary Christ confronts a marginalized woman with a simple question: “Give me to drink” (4:7). She responds with a defensive reminder that the “Jews had no dealings with the Samaritans” (4:9) who were usually ostracized as an ethnic group. The Jews hold that their descent from Jacob is the purer one, unadulterated by intermarriage as the Samaritans’ was. This woman is in a very uncomfortable position from the beginning of the conversation. She has also come to the well at noon. Drawing water, then carrying water any distance in the heat of the Middle Eastern day is burdensome. She must have had a compelling reason for her presence at that time. The well was a social gathering spot, a type of “watering hole” for women from the village and even herdsmen from the fields. It seems clear that the woman is avoiding people.

Jesus then asks her another question, a “who” question somewhat like hers: if she only knew Who was asking a drink from her, she would ask Him for water, and it would be “living water” (4:10), superior to that from the well. Defensively, she notes He has nothing with which to draw water from the well, unlike her rope and pitcher seen in the painting. She follows up with a history lesson: Jacob, a common ancestor, dug the well, and it gives good water, tasty and plentiful. Christ responds with an elaboration on His “living water.” The major difference, He says, between the types of water is their thirst-quenching properties. How she must have tired of the hot, dusty chore of fetching water from a well probably some distance from the village. Then she asks for His water in order to ease her workload: “Sir, give me this water, so that I will not be thirsty or have to come here to draw water” (4:15).

Next, Jesus changes the subject abruptly and tells her to call her husband. Here seems to be the moment of the painting, and the marginalization of the woman increases. With His hand outstretched Christ tells her she has had five husbands and is currently living with a man not her husband. Morally, the woman is on the fringe of society; undoubtedly this fact is the reason for her midday water run. In the painting, she tilts her head downward. She must have been astonished by His knowledge; she may have been ashamed. She certainly tries to deflect the conversation.

This woman, like most people, does not want to come directly to Jesus. But she moves one step closer: “I perceive that you are a prophet” (4:19). She poses a religious red herring question about the worship of God: whether the Jews were right about Jerusalem or the Samaritans about their mountain. Christ kindly answers her question, “Salvation is from the Jews” (4:22), from the line of David. She obviously knows her Old Testament and brings up not only the coming of the Messiah, but also His omniscience: “When He comes, He will tell us all things” (4:25). At this point Christ tells her, “I Who speak to you am He” (4:26).

She is on the fringes geographically. Though Jews would go miles out of the way to travel around Samaria if at all possible, yet Jesus “must needs go through” (4:4) the region. She is historically ostracized by the Jews as well and morally shunned by her village. But Jesus goes out of His way, literally, to tell her the truth about Himself. And she is the first to hear from His own lips that He is the Messiah, not only of the Jews, but of all who will accept His offer of living water. But it is the knowledge of her life that convinces her: she leaves her waterpot, goes into the village and tells all, “Come, see a man, which told me all things that ever I did: is not this the Christ? (4:29). The story ends with Christ staying two days in Sychar, Samaria, then returning to Galilee. There is no record of His working in any other town; it appears that meeting this woman and those of her village was His whole purpose for the journey into Samaria.

The Art

Bloemaert has symbolized the woman’s need by the empty copper pot near her feet; while the greenery at Christ’s feet is lush, testifying to the abundant life that Christ’s water gives. The choice of clothing color is also significant. While purple is the color of royalty, Christ’s inner garment is violet, a color representing love, truth, passion, and suffering. His outer cloak is a vibrant red, certainly an association with blood. As the Messiah, Christ would suffer a violent death for the sins of this woman and of the whole world, because He loved those who would surely die without His living water. That a dying Messiah offers living water is an interesting juxtaposition. The yellow of the woman’s gown signals revealed truth but can also signify degradation. Here Bloemaert’s color choices (his palette was distinctive) reveal the storyline too. A sinful, marginalized woman encounters revealed truth, both in word and in person. What she does with that truth removes her shame and allows her to live forever as a child of God.

Karen Rowe Jones, M&G board member

Published 2021

The Adoration of the Shepherds

Oil on canvas, 1625-30, signed with intials: P. DG.

Pieter Fransz. de Grebber

Dutch, c. 1600–1652/53

Pieter Fransz. de Grebber was born in Haarlem around 1600 to an artistic family. His father, his sister Maria, and his brothers Albert and Maurits were all gifted artists. What better place for de Grebber to be born at the beginning of the seventeenth century than Haarlem, the leading center of Dutch painting at that time.

His father Frans Pietersz. de Grebber, a painter and art dealer, taught Pieter initially and later apprenticed him to Hendrick Goltzius. Pieter primarily dedicated his artistic talent to history paintings of Biblical themes. He grew up and remained a devout Catholic often creating paintings for clandestine Catholic churches in Protestant Holland. De Grebber joined with Salomon de Bray in promoting the Baroque classicist school in Haarlem. He eventually joined the Guild of St. Luke in Haarlem and was later elected dean of the Guild. He also contributed to the music and literature of Haarlem as an amateur composer and poet. His artistic style, while uniquely his own, shows the influences of leading Dutch artists Peter Paul Rubens and Rembrandt and even Italian artist Caravaggio, whose style the artists in neighboring Utrecht emulated.

At first glance, this charming scene appears to be a family gathering around its newest member. A rising middle class in northern Europe desired art that related to them and their lives and sought portraits, still life, and domestic and rural scenes. De Grebber’s Adoration of the Shepherds beautifully marries a realistic, contemporary scene with the historical visit of the shepherds to the Christ Child. None of the figures appear in garments typical of first-century Palestine but of those of the seventeenth century furthering the ability of the contemporary viewers to relate to and connect with the subject of the painting. De Grebber intimately lights the scene with candlelight as the shepherds draw near to see the baby. Mary cradles Baby Jesus in her arms, and a fascinated young child gently touches the swaddled Christ under the adults’ careful supervision.

One cannot help but notice the theme of light in this story. When the angels appeared to tell the shepherds the good news, “the glory of the Lord shone round about them.” Such glory would surely have startled and even blinded them in the darkness of night. Upon hearing the angels’ tidings and praise to God, the shepherds immediately rushed to Bethlehem where they found Christ in a humble stable.

The Son of God came into a dark world to provide light and hope. After seeing the Light of the World with their own eyes, the shepherds spread the word of His birth and became messengers bearing the news of this Light come to illuminate the darkness in the hearts of men. De Grebber’s painting demonstrates that Christ offers His light to all people, and no matter how dark life may seem, He is there to illuminate and guide those who come to Him.

Rebekah Cobb, Registrar

Published in 2020

The Arrival at Emmaus

Oil on panel

Aert van der Neer

Dutch, c. 1604– d. 1677

Irony in life exists in the world of art as well as in other spheres. There are well-known artists that have died poor or their works were lightly esteemed. Such is the painter of M&G’s The Arrival at Emmaus, Aert van der Neer. He is one of many Dutch landscape artists of the seventeenth century. Born in Gorinchem in the northeastern part of the country and residing mainly in Amsterdam, he is part of the Dutch Golden Age. He was a steward in the early part of his adult life then became more involved in painting in his late thirties or early forties. His wife, Lisabeth, was the sister of artist, Rafael Govertsz Camphuysen (also represented in M&G’s collection).

While Aert died in poverty, one of his sons, Eglon excelled as an artist and ultimately settled in Dusseldorf as a court painter.

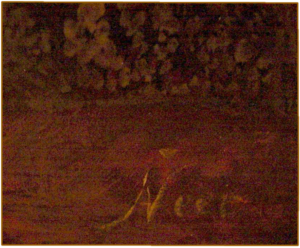

The style of van der Neer and his friendship with painter Aelbert Cuyp led them to work together on a number of paintings. Aert often painted the basic composition, and Aelbert would add the finer details. Works exist with the initials of both artists inscribed on them. However, M&G’s painting is signed only by Aert van der Neer as Neer. (include image: signature detail)

The style of van der Neer and his friendship with painter Aelbert Cuyp led them to work together on a number of paintings. Aert often painted the basic composition, and Aelbert would add the finer details. Works exist with the initials of both artists inscribed on them. However, M&G’s painting is signed only by Aert van der Neer as Neer. (include image: signature detail)

For the whole of his life, Aert never varied his painting style as seen in his many moon-lit landscapes and peopled scenes depicting a centrally placed river. Regardless of some of his repetitive compositional choices, he illustrated favorite parts of his country in an unmistakable way. His landscape style was so frequently imitated during and after his life that author Christopher Wright explains, “Thus—although this is not often realized—van der Neer can be said to have been one of the most influential Dutch painters.”

The Arrival at Emmaus joined M&G’s collection in 1974. It is one of the few scriptural subjects depicted by the artist. Luke 24:13-35 tells the narrative of Christ joining two, heavy-hearted disciples en route to Emmaus from Jerusalem. Christ asked about their conversation, and not recognizing Him, the two shared the tragic account of Christ’s crucifixion and their belief that His missing body could not be located. Little did they know as Christ explained the Old Testament messianic scriptures on their journey, that He was there with them. When they arrived in Emmaus after a nearly seven-mile journey, the two men graciously urged Him to “abide with” them. Christ took the position of host at their supper table and blessed and broke the bread. At that moment, He opened their eyes (v. 31) to understand Who He was—their risen Messiah. Then, with uncontained joy and full comprehension of why their hearts “burned within” as He had spoken the scriptures on the road, they immediately left Emmaus and returned to Jerusalem! There they exclaimed to the disciples that “the Lord is risen indeed” (v. 34).

Visible in this painting is the representation of Emmaus as a Dutch town. A seventeenth-century cathedral is prominent in the background as daylight is receding and the ducks begin nesting down for the night. The two disciples are seen inviting Christ to be their guest, a guest who would vanish from their sight and leave them with a greater realization of who He is. As the season of Advent approaches, may we too recognize who Christ truly is.

John Good, M&G Security Manager

Additional Resource:

The Dutch Painters, 100 Seventeenth Century Masters

Published in 2020

This arresting Mary Magdalene Turning from the World to Christ identifies Jan van Bijlert with the Utrecht Caravaggisti. The work is a beautiful blending of dramatic qualities of naturalism with the brilliant precision of classicism.

In this triptych the artist beautifully pictures several of the most familiar Christmas story events.

Jan Gossaert, called Mabuse, was one of the first Netherlandish painters to integrate an Italian and Northern style. His beautiful Madonna of the Fireplace in one stunning example of his skill.

Monthly Update

Sign up here to receive M&G’s monthly update and collection news!

EXPLORE More Online Features

Speakers Bureau

We can speak for your retirement group, civic club, church fellowship, or book club. Contact us here or at 864-770-1331.

Support Our Work

Make a Gift to M&G to help our current work and future plans.