Dresden Monumental Armorial Urn

Porcelain, c. 1888-1901

Carl Thieme

German, 1838-1888

Carl Thieme was born in 1838 in Potschappel, a village on the outskirts of Dresden, Germany. In 1856 he was employed by the Meissen Manufactory, where he honed his porcelain modeling, sculpting, and painting skills under expert craftsmen. In 1865 he opened a porcelain and antique shop in Dresden. At this time he was also a hausmaler (a free-lance porcelain decorator) of unpainted items produced by Meissen and other manufacturers. In 1872 he opened the Dresden Saxonian Porcelain Manufactory in Potschappel. Thieme collaborated with prominent porcelain artists, such as Julius Konrad Hentschel, Eduard Eichler, and Ernst Bohne, and the company grew rapidly. The Dresden Saxony Porcelain Manufactory gained international recognition and received prestigious awards at national and international exhibitions.

Carl Thieme was born in 1838 in Potschappel, a village on the outskirts of Dresden, Germany. In 1856 he was employed by the Meissen Manufactory, where he honed his porcelain modeling, sculpting, and painting skills under expert craftsmen. In 1865 he opened a porcelain and antique shop in Dresden. At this time he was also a hausmaler (a free-lance porcelain decorator) of unpainted items produced by Meissen and other manufacturers. In 1872 he opened the Dresden Saxonian Porcelain Manufactory in Potschappel. Thieme collaborated with prominent porcelain artists, such as Julius Konrad Hentschel, Eduard Eichler, and Ernst Bohne, and the company grew rapidly. The Dresden Saxony Porcelain Manufactory gained international recognition and received prestigious awards at national and international exhibitions.

Thieme died in 1888, and the business was eventually taken over in 1896 by his son-in-law, Karl August Kuntzsch (1855-1920). Kuntzsch was a talented modeler who started a tradition of lush, sculpted floral decorations. The business flourished and employed several hundred people. In time, the company became known as Dresden Porcelain. After the glory days of Thieme and Kuntzsch the company frequently floundered as it went through a succession of owners and directors. Tragedies destroyed its irreplaceable stock of over 12,000 models. At times Dresden Porcelain employed less than a dozen people, and by 2020 it had only two employees, tasked with selling the remaining pieces. Today the building which once produced Dresden Porcelain serves as a museum.

From its inception the Dresden Saxonian Porcelain Manufactory used various marks. The mark on the bottom of M&G’s urn indicates that the company produced it between 1888 and 1901 and that Thieme is credited with its design, even though it was produced after his death. The sculpted flowers may be early works of Kuntzsch or his apprentices.

A Monumental Urn

Monumental porcelain urns are generally large, ornate, highly decorated, and rarely intended to store anything. Some have ornate lids. Some come in pairs. The Dresden Saxony Porcelain Manufactory urns are legendary for their intricate beauty.

M&G’s monumental urn is 30 inches high. On its square base is a spindle-shaped pedestal with a pair of sculpted young people gathering flowers; between them, on the front, is a painted scene of Cupid and Venus.

In mythology, Cupid is the god of love and desire. He is often depicted as a mischievous, winged child, armed with a magical bow and arrows which he uses to strike people and gods madly in love. He enjoys the chaos of broken hearts and unexpected matches. Venus, the goddess of love, beauty, and fertility, is Cupid’s mother. In some stories Cupid goes too far with his pranks, and Venus stops him by taking away his bow. The scene painted on the front of the pedestal of M&G’s urn depicts Cupid trying to reclaim his bow. (Figure 1)

The body of M&G’s urn is ovoid, with the smaller end pointed down. Two, curved handles are embellished with gold. The back of the urn’s body features hand-painted florals. The front of the urn has two garlands of sculpted flowers and fruits, surrounding a painted scene of the Expulsion of Hagar. (Figure 2)

The Biblical story of Abraham, Sarah and Hagar is a found in the Book of Genesis chapters 16, 19 and 20. It is also mentioned in the Quran. Abraham was a righteous man chosen by God. God promised that he would become the father of a great nation. However, Sarah, Abraham’s wife, was unable to conceive.

In an attempt to fulfill God’s promise, Sarah suggested that Abraham take her Egyptian maidservant, Hagar, as a concubine. According to the customs of that time, a child born to Hagar would be considered Sarah’s child. Abraham agreed. Hagar became pregnant and gave birth to a son named Ishmael.

As years passed, God appeared to Abraham and reiterated the promise, specifying that Sarah would bear a son. Despite their old age, Sarah conceived and bore Isaac. This miraculous birth fulfilled God’s promise, and Isaac became the child through whom the covenant with Abraham was established.

Tension grew between Sarah and Hagar, and eventually, Sarah asked Abraham to send Hagar and Ishmael away. Reluctantly, Abraham did so. This is the event portrayed on M&G’s urn. The 100-year-old Abraham, the elderly Sarah and the young Isaac are central in the painted scene. The departing Hagar with her back to viewer is leading Ishmael into the wilderness. (The seated female is unknown, probably a servant introduced by the artist to balance the picture.)

In the wilderness Hagar and Ishmael faced desperation and thirst. Hagar thought they would die. However, God heard their cries and provided for them. God also promised to make a great nation of Ishmael’s descendants. He is the ancestor of the Arab people. Abraham, Sarah, Isaac, Hagar, and Ishmael’s story is one of faith, obedience, and the fulfillment of divine promises, emphasizing the importance of trust in God’s plan.

An Armorial Urn

An armorial porcelain piece includes a coat of arms. Occasionally large sets of armorial dinnerware have been commissioned. Other times a centerpiece or single serving piece is armorial. In the case of armorial monumental urns, there is generally only one created, but occasionally there are pairs.

Monumental armorial urns in porcelain were generally commissioned to commemorate an event: winning a battle, the completion of a major project, a significant anniversary. A piece with two family crests, like M&G’s, would most likely be a wedding or anniversary gift, or perhaps commemorating some joint victory or project completion. As the recipient proudly displayed the beautiful piece, it would serve as a reminder of the event.

On M&G’s urn just under the painted scene of Hagar, two winged cherubs hold a swag of small, sculpted flowers which appear to support the crest-bearing medallion topped by a sculpted crown. The right crest has crossed swords, a green ornamented band, and a stylized purple crown, all of which are parts of Saxony crests. The crest on the left has not yet been identified.

On M&G’s urn just under the painted scene of Hagar, two winged cherubs hold a swag of small, sculpted flowers which appear to support the crest-bearing medallion topped by a sculpted crown. The right crest has crossed swords, a green ornamented band, and a stylized purple crown, all of which are parts of Saxony crests. The crest on the left has not yet been identified.

Although today we may not know what M&G’s armorial urn commemorates, we can still appreciate its delicate beauty and admire the supreme craftsmanship required to produce it.

William Pinkston, retired educator and M&G volunteer

References

Dresden Porcelain Studios: Identification & Value Guide by Jim and Susan Harran

Updated from 2013 and republished to reflect new research in 2024

Early strong boxes were constructed of resilient and heavy wood that later was reinforced with metal straps and nails. As advancements were made in metallurgy, corresponding improvements were made in safe construction. M&G’s seventeenth-century safe would have been forged after the introduction of iron plates, and was probably crafted in Germany, where much of Europe’s iron work was manufactured. The cities of Southern Germany, such as Nuremberg, were particularly known for the craftsmanship of their blacksmiths and locksmiths, and demand was high for their lock boxes not only in Germany, but beyond.

Early strong boxes were constructed of resilient and heavy wood that later was reinforced with metal straps and nails. As advancements were made in metallurgy, corresponding improvements were made in safe construction. M&G’s seventeenth-century safe would have been forged after the introduction of iron plates, and was probably crafted in Germany, where much of Europe’s iron work was manufactured. The cities of Southern Germany, such as Nuremberg, were particularly known for the craftsmanship of their blacksmiths and locksmiths, and demand was high for their lock boxes not only in Germany, but beyond.

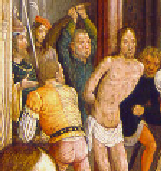

ng sleeve flaps, or even hats into pointed or squared scallops. This trend was especially popular during the late Middle Ages. The man in red at Christ’s crowning with thorns features dagging at the bottom of his doublet (jacket).

ng sleeve flaps, or even hats into pointed or squared scallops. This trend was especially popular during the late Middle Ages. The man in red at Christ’s crowning with thorns features dagging at the bottom of his doublet (jacket). tried to take matters into his own hands by declaring a law that “no Knight under the estate of a lord, esquire or gentleman, nor any other person, shall wear any shoes or boots having spikes or points exceeding the length of two inches, under the forfeiture of forty pence.” The law was ineffective, and the trend lasted until 1480! The man, at right foreground and near to Pilate, models poulaines.

tried to take matters into his own hands by declaring a law that “no Knight under the estate of a lord, esquire or gentleman, nor any other person, shall wear any shoes or boots having spikes or points exceeding the length of two inches, under the forfeiture of forty pence.” The law was ineffective, and the trend lasted until 1480! The man, at right foreground and near to Pilate, models poulaines.  ed for ceremonial occasions as seen here on the soldier kneeling in the foreground.

ed for ceremonial occasions as seen here on the soldier kneeling in the foreground. horns features

horns features a parti-colored doublet. At the beating of Christ, the man to the left of Christ also wears a parti-colored doublet.

a parti-colored doublet. At the beating of Christ, the man to the left of Christ also wears a parti-colored doublet.