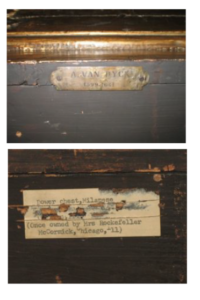

Bust of Henri II, King of France

Bust of Catherine de’ Medici, Queen of France

Glazed Terracotta

Girolamo della Robbia (attr. to)

Italian, 1488–1566

Click on the links throughout the article to view additional artists’ works and reference material.

Heading into the month of November, the themes of family and tradition are strongly emphasized. Throughout the Museum & Gallery, there are many examples of studio traditions passed down between family members such as father to son, uncle to nephew and even father to daughter. Of these there are few families who have achieved such renowned fame as the Della Robbia family. Founded in Florence by Luca Della Robbia, the family workshop produced sculpture for more than 100 years and was considered one of the most successful studios of the Renaissance.

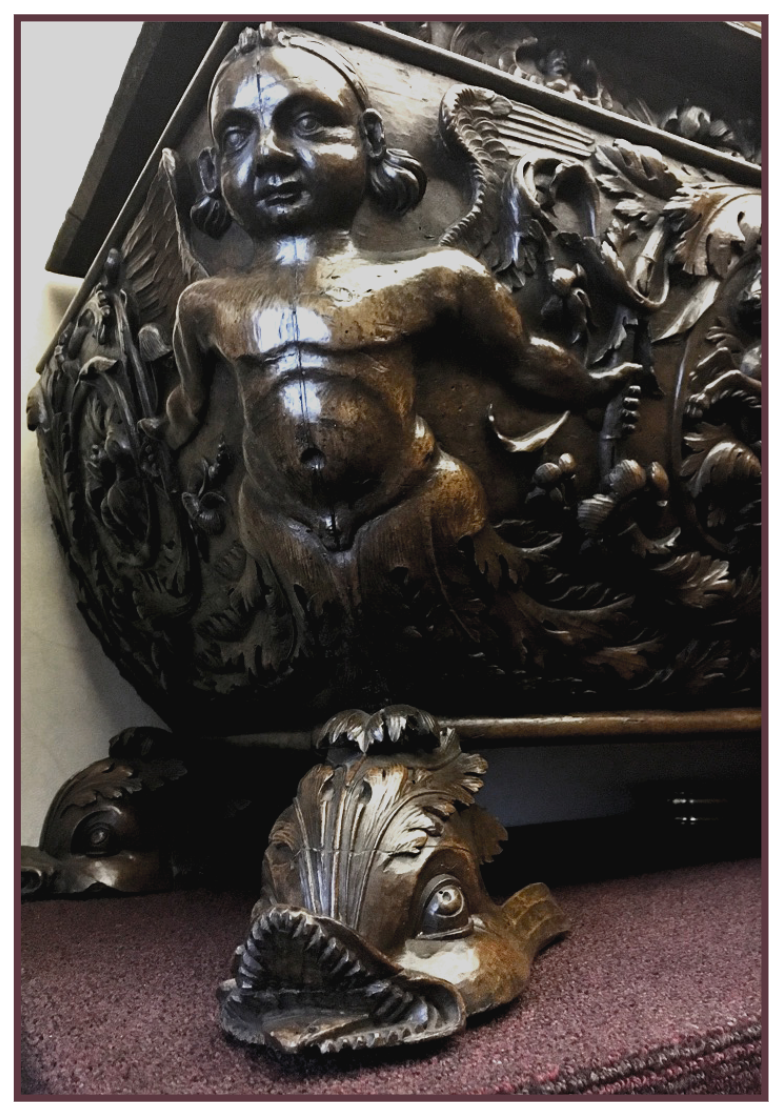

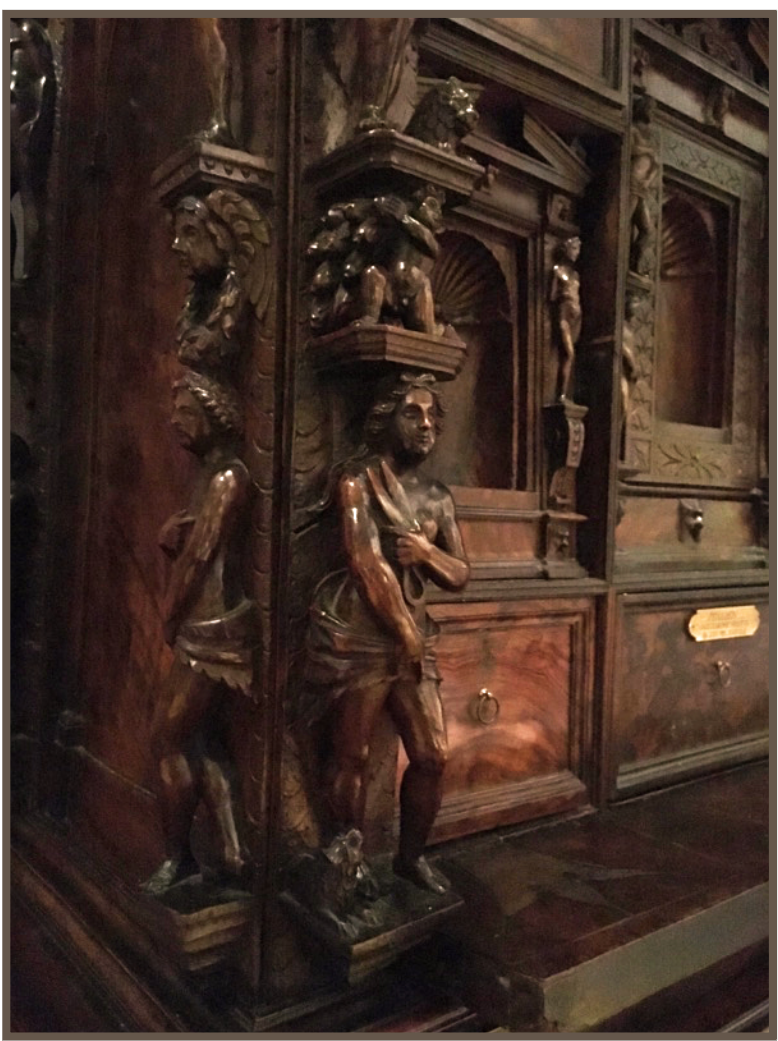

What made the Della Robbia family so successful was their contemporary approach to sculpture and their luminescent glazing. Sculpture began to take new forms in the Renaissance, especially in the use of a forgotten medium—clay, which was revived for many reasons. It was easy to model and cast, which allowed delicate detail; and it was an inexpensive material. Clay was considered a humble medium that encouraged piety and did not distract from the holiness of the subject it depicted.

Luca is credited with the invention of the glaze, the family studio’s distinctive trademark, which effectively combined painting and sculpture. Many reasons are given why he developed the new glazing technique ranging from aesthetic to economical or both. The glaze was a ceramic treatment of the clay that protected the clay, making it impermeable. It also rendered sculpture, in Giorgi Vasari’s words, “almost eternal.” Hailed as a major artistic and scientific discovery, the glazed terracotta rapidly became desired throughout Florentine society.

After Luca, the studio was passed on to his nephew, Andrea, and then to Andrea’s sons. From Florence, the studio was carried to France in 1517 by Girolamo della Robbia, the youngest son of Andrea. At this time, King Francis I had been inviting many Italian artists such as Girolamo to encourage an artistic Renaissance in France. Girolamo created many sculptures, altarpieces and intricate architectural elements for the king and his court. After the death of King Francis, Girolamo went home to Florence but later followed Queen Catherine de’ Medici to Paris to continue making art until his death in 1566. Two years later, Vasari wrote “not only did [Girolamo’s] house die out…but art was deprived of the knowledge of the proper method of glazing.” Despite the family’s closely guarded glazing secrets, legend tells that a Della Robbia housemaid stole the glazing technique and passed it on to Benedetto Buglioni and his family.

Located in the Italian Mannerist gallery at M&G, two large terracotta busts immediately arrest the attention of guests. Their powerful presence and beautiful glazing draw viewers in to inquire the identity of the sitters. Both are attributed to Girolamo and are reminiscent of the works for which the della Robbia family is so famous.

When Dr. Bob Jones Jr., founder of M&G, purchased the pair, the figures were originally thought to be Cesare and Lucrezia Borgia, son and daughter of infamous Pope Alexander VI. However, due to Girolamo’s workshop being more centrally located in France, it is more likely the figures are King Henri II (son of Francis I) and Queen Catherine de’ Medici. The figures could also be French courtiers who were wealthy enough to afford their portraits in sculpture.

Even though the art of sculpture seeks to capture a likeness or identifiable features, it should be noted that most sculptural portraits remain unidentified. Whoever these two actually were, they have truly been immortalized and given as Vasari says an “almost eternal” look. From their pedestal, they stand as a testament to the artistic tradition and genius of the Della Robbia family.

KC Christmas, Docent and Guest Services Attendant

Published in 2016