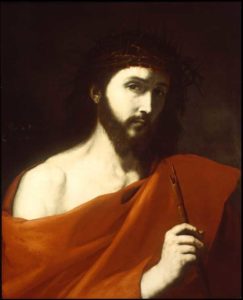

The Entombment of Christ

Oil on canvas

Jusepe de Ribera, called Lo Spagnoletto

Spanish, 1591-1652

While Italian Renaissance artists benefited from a mutual sharing of progressive artistic advancements, Spanish artists remained deeply provincial until the Baroque age. Jusepe de Ribera spent his career in the Spanish-controlled kingdom of Naples where he adopted the naturalism of Caravaggio. Ribera’s works, imported from Naples to Spain, brought to other Spanish artists the lighting effects of Caravaggio, the most influential Italian painter of the 17th century. In addition, viceroys brought both originals by Caravaggio and copies back to Spain. Caravaggio’s dramatically deep chiaroscuro (the effect of light and shade) and rugged realism (portraying as accurately as possible the natural world) are evident in this work by Ribera.

When looking at religious art, it is best to begin with the source of the work. In this case it is the Biblical accounts of the burial of Christ which are detailed in all four of the Gospels and reveal the cast of characters present in the painting (Matthew 27, Mark 15, Luke 23, and John 19). After His sacrificial death on the cross, Christ was hastily buried because of the imminent start of the Sabbath celebration. Joseph of Arimathea, a just man who had voted against the action of the Sanhedrin to put Christ to death; Nicodemus, another member of the Sanhedrin who had sought out Jesus by night to inquire how one could enter the kingdom of heaven; and Mary Magdalene, a wealthy follower of Christ who had seven devils cast out of her, are all mentioned as being present at the tomb. Other women are mentioned as well, but John the disciple and Mary, Christ’s mother are not mentioned in the Gospels as attending, but Ribera chooses to adhere to tradition and include them both.

Traditional Imagery

So, who is who? Traditional iconography would dictate that John is the young man in the back right who is wiping away his tears. Joseph would be the older man in the forefront with the red cloak; he is, after all, a wealthy man who has donated his new tomb for the Savior. That leaves Nicodemus as the older man at the head of Christ. Because of the long, free blonde hair, Mary Magdalene is in the center with Mary the mother of Christ in the shadows.

Though Christ’s body is pallid and remarkably whole given the scourging and the crowning of His head with thorns, the open wound in His side signifies Christ’s personal cost for man’s salvation from sin, which He purchased for all. Bringing forth blood and water, the soldier’s action revealed the emptying of life that sustained Christ until the payment of man’s sin was complete. Ribera places the body on a stone surface, likely the burial table in the tomb, which has a sharply defined corner. This compositional detail reflects the words of the Apostle Peter, referencing the Psalmist David and the prophet Isaiah who characterize the coming Messiah as a “rejected” stone of “stumbling and a rock of offense” which has become the “cornerstone.” A cornerstone sets the stability of the entire building, and the reader is told that “whoever believes in him will not be put to shame” (I Peter 2:6-8). Clearly, the kingdom of God is set upon the foundation of the death of Jesus Christ.

Ironically, however, at His death and burial, no one believed He would rise again. The incredulity of the disciples when the women reported the angel’s words at the empty tomb reveals that they did not understand the teaching of Jesus that He “must suffer many things and be rejected by the elders and chief priests and scribes, and be killed, and on the third day be raised” (Luke 9:21). But anyone who does understand that saying, including the multitude of Christ’s followers in the days following the resurrection, can be assured that he or she will not be disappointed in believing and accepting the death of the sinless Christ to pay for their own sins.

What is interesting about Ribera’s composition of the Entombment is the placement of the two women. Mary the mother of Christ is no longer the prominent woman; she is nearly hidden in the shadows while Mary Magdalene is in the foreground mourning Christ with clasped hands and downcast eyes.

Scriptural Accounts

Given the controversies associated with the Magdalene, it is important to focus on what the Scriptures tell about her:

- Luke tells that “some women who had been healed of evil spirits and infirmities” followed Christ as He traveled. The first listed is “Mary, called Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out” (8:2). These women are also characterized as supporting Christ and His disciples “out of their means” (Luke 8:3).

- At the crucifixion, John reports that Mary was “standing by the cross of Jesus” with Mary the mother of Christ (19:25).

- Mark then relates that “Mary Magdalene and Mary the mother of Jesus saw where [Jesus] was laid” (15:47) and with “the women who had come with him from Galilee . . . returned and prepared spices and ointments” (Luke 23:55-56) for the more detailed burial after the Sabbath was over.

- All four Gospels reveal that Mary Magdalene was up early on the morning after the Sabbath on her way to the tomb to minister to the Lord’s body. Here, clearly, is the biblical record of a woman dedicated to the life and memory of the One who had rescued her from Satan’s power.

Artistic Depiction

Ribera’s reversal of prominence may reflect the truth that at Christ’s death, His relationship to His mother ended. As the eldest son, now unable to care for His mother any longer, He transferred Mary to John’s care. But the prominence of Mary Magdalene in the central foreground of the group of followers mirrors the tender truth of a Luke 7 parable told by Jesus about a moneylender who forgave a large and small debt of two men as an illustration about another woman only identified as “a sinner” (likely a woman of loose morals). Although Magdalene is not this woman, her life attests to the same love that the “sinner” had for her Lord. Christ explains that the unnamed woman is like the man with the greater debt. Her “sins, which are many, are forgiven—for she loved much. But he who is forgiven little, loves little.” The Magdalene had not one, but seven, devils cast out of her; there is no telling the damaging physical effects of her demon-possession. And though the demons were aware of Christ’s identity as the Messiah, they certainly would have kept their victim from realizing and accepting that truth for herself. The Magdalene of Ribera’s focus had much to be thankful for, and her dedication to the service of both the living and dead Christ reveals the depth of that love.

At the tomb early that Easter morning, Mary Magdalene and her companions were told that Christ was risen and instructed to tell the disciples. What a privilege to share that good news! But Mary was more than a messenger. Christ appeared to hundreds of His disciples in the days after His resurrection, but Mark relates, “Now when He rose early on the first day of the week, He appeared first to Mary Magdalene, from whom He had cast out seven demons” (16:9). Given her love for Christ as evidenced by her eagerness to prepare His body properly for burial, it is no accident that she is the first to see the risen Christ whom she worships immediately, clasping His nail-pierced feet—the physical manifestation of Christ’s power to defeat death, her demons, and save her eternal soul.

Ribera’s composition places the viewer within the circle of mourners around the dead Christ with nothing in the composition to separate the viewer from the body itself. Thus, we are made to react as if we were within the frame. Do we see ourselves as sinners, loving Christ dearly, but devasted at His death, demoralized by the apparent emptiness of His promises of the kingdom of God and the forgiveness of sins? Will we, like Mary Magdalene, recognize our Savior and hear Him say that He is “ascending to my Father and your Father, to my God and your God” (John 20:17)? We will, if this Easter, we believe the Gospel accounts of the Christ whom Mary followed faithfully.

Karen Rowe Jones, M&G board member

Published 2021