Victorian artist, Eyre Crowe does a masterful job of recreating that moment in the town of Wittenberg, Germany that set in motion the Protestant Reformation.

Tag Archives: Martin Luther

This month’s video, also from M&G’s Luther exhibition, highlights the impact of the Bubonic Plague on the great reformer and his culture.

During the 500th anniversary marking Martin Luther’s nailing of his 95 theses to the door of Wittenberg’s chapel, M&G created an exhibition exploring his life and continuing influence. This video from that exhibition focuses on his musical legacy.

Wittenberg, October 31, 1517

Oil on canvas, Signed and dated: E. Crowe, 1864 (lower left)

Eyre Crowe, A.R.A.

English, 1824–1910

Click on links for additional reference information.

Martin Luther truly changed the course of history, but it was English painter Eyre Crowe who captured the defining moment. Wittenberg, October 31, 1517, has long been a favorite of M&G guests for its historical accuracy. “Story paintings,” a common name for the genre of this piece, invite investigation, and recent research on Crowe’s work has revealed that there is “more of the story to tell.”

The obvious historical event being pictured here is Luther’s nailing of the 95 Theses to the door of the University of Wittenberg Chapel. But it may very well be that Crowe purposely wove together additional personages and objects which served to emphasize the crux of the matter which prompted Luther’s action – plenary indulgences offered by the Roman Catholic church.

The prominent horseman on the left, Johann Tetzel, holds in his left hand a grid-like object with dangling metal bulla. The embedded papers, inscribed with numbers representing days or years in purgatory that could be lessened, were purchased by anxious parishioners seeking to relieve themselves or their dead of suffering. Coins clunking in the coffer Tetzel holds evokes the rhyme that still rings through the halls of history.

Worshippers could also acquire relief from anguish by employing a prayer to Mary, Christ’s mother, called The Rosary. In order to count the component invocations, or “tell the beads,” individuals held an object known as a rosary. Rosaries took on many forms (chaplets, ropes, decade and pomander rings) of varying materials (wood, glass, seeds and plastic). Crowe identifies medieval rosary rings reminiscent of a carnival ring toss game by placing examples in the foreground. He continues to add additional weight to his emphasis by sprinkling rosary types, either held or worn, near the significant people in Luther’s life. Research required to accomplish such a historically accurate piece likely led Crowe to such paintings as The Arnolfini Wedding by Jan van Eyck and The Feast of the Rosary by Albrecht Dürer both of which contain prayer beads.

Prominently represented left center and wearing regal garb is Margaret of Münsterberg with her son George III clinging to her skirt. Bereft of her husband, Prince Ernest I of Anhalt-Dessau, and left with three sons too young to assume regency, Margaret undertook her new position as princess regent with vigor and religiosity. Strongly adverse to the Reformation, she organized the League of Dessau. Though unsuccessful in thwarting the spread of the Reformers’ teaching, it is very possible the League exposed her sons to Luther and his doctrine. Letters were exchanged between Luther, Margaret, and her offspring, which resulted in her sons’ adopting the tenets of Lutheranism in their adult years. George ultimately was ordained by Luther, making him the only German prince to be inducted into the Lutheran clergy.

As if to make a final point on the issue of indulgences, the artist places in each of Margaret’s hands a rosary – one a ring and the other a wooden beaded arrangement. A woman of means who could certainly afford some of the extravagant materials used for rosaries of the period, Margaret, however, emulates her sovereign ruler, Charles V, by clutching a poor man’s wooden one.

In Eithne Wilkins’ The Rose Garden Game; the Symbolic Background to the European Prayer Beads, the author details the varying philosophies associated with a worshipper’s choice of rosary materials:

Beauty of material and elaborate workmanship over against ascetic simplicity remains an issue, as might be expected throughout the centuries. The principle of making the external object conform with the interior purpose can be interpreted in two ways. One may feel, as Lady Godiva did in the eleventh century, that it is fitting to count one’s prayers on jewels, for they are being offered to God. Or one may feel that a wretched sinner like oneself should not presume to offer prayers on any but the plainest beads. This sort of self-abasement may even be more effective than any flashing of gems. That was so when in 1532 and again in 1541 the Emperor Charles V, taking part in the Corpus Christi procession at Regensburg, carried ‘ordinary little brown wooden beads’: it was, the commentator pointed out, ‘to mark his humility.’ The ostentation of some people’s display evoked criticism as early as 1261, and fashion was not always on the side of luxury: Emperor Charles V carried ordinary little brown wooden beads…to mark his humility.

Crowe has also included the historical likenesses of other key people from sixteenth-century Wittenberg on the right side of the painting. Katherina von Bora, the nun who eventually married Luther, is present with Luther’s father, mother, and sister. To the left of Katherina von Bora is Luther’s artist friend, Lucas Cranach, the Elder.

Wittenberg, October 31, 1517 is exhibited as part of Luther’s Journey: Experience the History on view in the Gustafson Fine Art Center on the campus of Bob Jones University. Information about the exhibit and the accompanying tour is available here: www.museumandgallery.org/specialized-tours/

Bonnie Merkle, Internal Database Manager and Docent

Published in 2017

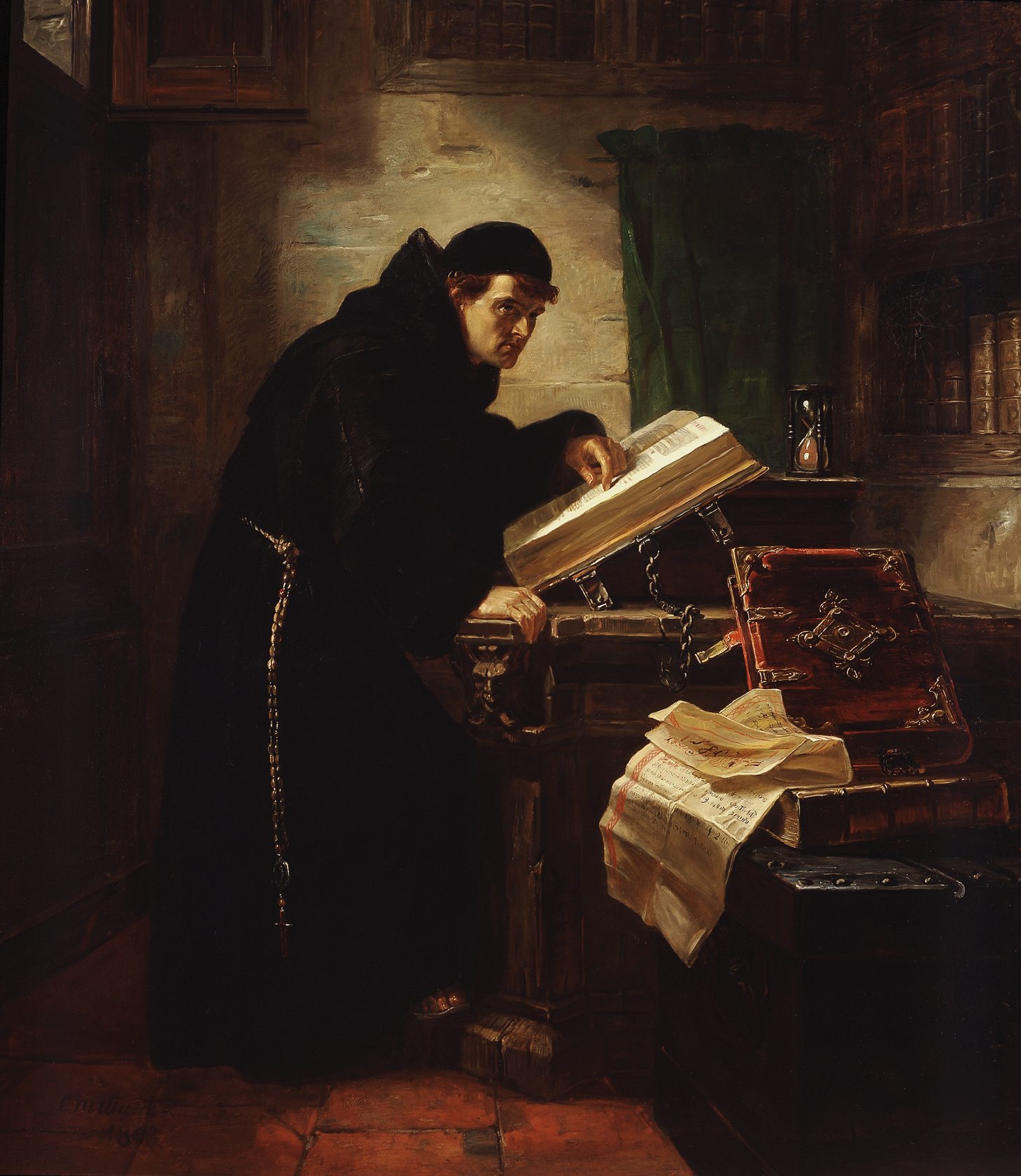

Martin Luther Discovering Justification by Faith

Oil on canvas, Signed and dated: E M Ward, R A, 1868 (lower left)

Edward Matthew Ward, R.A.

English, 1816–1879

Edward Ward’s portrait of Martin Luther Discovering Justification by Faith draws on traditional elements of portraiture. Like most scholar portraits, this one places the sitter in his “study” surrounded by precious manuscripts and books on theology.

An enormous Bible is chained to the lectern. Bibles were rare and expensive to construct during the sixteenth century and were usually chained so that they would not be moved or lost. But here the chain is also symbolic. In the context of the reformer’s inner turmoil, the chain represents the inaccessibility of God’s Word—an obstacle that Luther is about to overcome through his discovery. This moment of enlightenment is also foreshadowed by the light streaming in through the open window, a common motif symbolizing heavenly illumination.

In addition, the hourglass as a symbol of time represents not only the brevity of this life (through the falling sand) but also the possibility of resurrection (through reversing the glass).

Like Ward’s beautifully rendered portrait, the following fragment from Luther’s autobiography vividly captures the power of this moment:

Night and day I pondered until I saw the connection between the justice of God and the statement ‘the just shall live by his faith.’ Then I grasped that the justice of God is that righteousness by which, through grace and sheer mercy, God justifies us through faith. Thereupon I felt myself to be reborn and to have gone through open doors into paradise. The whole of Scripture took on new meaning, and whereas before ‘the justice of God’ had filled me with hate, now it became to me inexpressibly sweet in greater love. This passage of Paul became to me the gate of heaven.

Click on the dropdown information below for further insights:

Although opposed to the veneration of images, Martin Luther did not object to using art in worship or in education. According to Luther, images “are neither good nor bad.” They are “unnecessary and we are free to have them or not.” He went on to say that visual art may be of considerable benefit in preaching and teaching the good news (as his artist friends the Cranachs sought to do). However, the leading Swiss reformer Huldrych Zwingli disagreed vehemently with Luther on this issue. Zwingli who preached for twelve years at the famed Grossmünster’s pulpit in Zurich ordered all altar paintings and statues removed from the church. This church, which still stands today, remains “quite bare, entirely stripped of the statues and paintings denounced by Zwingli.”

As the years passed the debate on the use of images in worship and religious education became less strident, though differences remained. For example, unlike Luther’s followers, artists like Jan Victors who embraced Calvin’s ideas refused to paint images of God (including God the Son), opting to focus on Old Testament scenes or New Testament parables.

Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac was one subject that captured the imagination of those on both sides of the debate. This Old Testament narrative adumbrating Christ’s atoning grace was central to all Protestant theologians, but the prophetic vehicle allowed artists who held views similar to Zwingli or Calvin to avoid violating their conscience in visually rendering God the Son.

The Sacrifice of Isaac by Lucas Cranach, the Elder, a friend and follower of Luther captures the climactic moment of the story.

The reproduction below is by one of Calvin’s followers, Jan Victors. Victor’s rendering of the biblical narrative captures the intimate moment between father and son just before Isaac is bound the altar.

Donnalynn Hess, Director of Education

Published in 2017