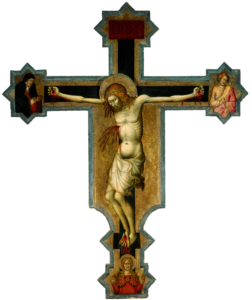

Descent from the Cross

Polychrome and giltwood, c. 1570

Unknown Spanish, 16th century

Renaissance artists employed various media and techniques to communicate their subject matter with power and beauty. This mid- to late-16th-century giltwood and polychrome relief by an unnamed artist (likely Spanish) demonstrates both artistic mastery and devotional power. It was once part of a larger altarpiece yet communicates clearly on its own.

A relief sculpture is normally attached to a background of the same material, and the degree of projection from that surface determines the terms used. Low relief, or bas-relief, project only a little. High relief denotes significant freedom from the background and can look like the figures are about to burst free from their surrounds. Finally, in sunken relief (or intaglio), subjects are carved below the level of their surroundings.

Gilding, the decorative technique of applying a thin layer of gold on a solid surface, dates back to Egypt. Herodotus mentions the Egyptians’ skill in gilding wood and metal, and many examples of their work remain to this day. The Sumerians (with objects dating back to 2600-2400 B.C.), Ancient Chinese, Old Testament Israelites, Ancient Greeks and Romans also utilized very thin sheets of hammered gold to overlay important objects of wood, stone and metal.

To produce fine furniture or sculpture, artists first carved plain woods like pine, beech or limewood. They then

added numerous layers of gesso (a type of plaster made by mixing fine chalk or gypsum with animal glue and water). Initial applications of the gesso filled imperfections in the wood, and subsequent layers built up a smooth surface that could be carved with greater detail than wood and rendered a top layer that could be gilt, painted, or otherwise decorated. The depth and crispness of this final surface indicates the craftsman’s skill.

The quality of M&G’s relief sculpture shows gilding expertise, but its polychromy adds to its power. Polychrome (literally, “many colored”)—pigmented wood, stone or terracotta—also dates to Egypt and the process refined over time. Over the millennia artists employed a wide range of pigments, painting media, and surface applications to embellish their work, and specialization occurred.

In Spain, the production of religious sculptures was governed by designated guilds. The Guild of Carpenters carved the wood and gesso, and the Guild of Painters was responsible for all decoration. Specific terminology came to describe specific skills. After the pieces were carved, painters used flesh tones for hands, faces, and feet (a process called Encarnacion). Estofado, which means “quilted silk,” was the skill of simulating rich fabrics through the layering of gold or silver leaf.

M&G’s sculpture demonstrates mastery of all these skills in an emotionally intense representation of Jesus’ followers lowering Him from the cross. Christ is the central figure—emphasized both by His placement on a diagonal in the center and by the fact that He is the only figure painted entirely in flesh tones. Around Him gather His mother, Mary (on the right), Mary Magdalene (immediate left, her hair cascading over her shoulder), Mary’s sister, and Mary the wife of Clopas. Behind Jesus, the Apostle John (at Christ’s right shoulder) and Nicodemus (left shoulder) bear the weight of His body. To the far right, two men pry open a sarcophagus. On the far left, stands Joseph of Arimathea, who had asked Pilate for Jesus’ body and donated both his new grave and linen to wrap Christ’s body. His headwear denotes Joseph’s status as a member of the Sanhedrin, and the striped pattern etched on its gilding matches that on the long swath of linen he is showing to the two women beside him. Taut carving of the trees, leaves, and clothing bring the scene to life and gilt patterns play across the various fabrics, the tomb, and the background plants and clouds. All of these techniques coalesce to convey the grief and dedication of Christ’s followers.

At the devotional center, as in history, is Jesus Christ—His redemptive work done, His burial imminent, and His victory over death yet to come.

Dr. Stephen B. Jones, M&G Volunteer

Bibliography

Metmuseum.org

Nationalgallery.org.uk

Hall’s Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, James Hall

Understanding Paintings: Themes in Art Explored and Explained, Alexander Sturgis and Hollis Clayson

Published 2025