Sorrowing Virgin

Glazed Terracotta, c. 1500

Andrea della Robbia

Florence, 1435-1525

Andrea della Robbia was born into a family known for artistic innovation. His uncle, Luca della Robbia pioneered glazed terracotta as a durable and expressive sculptural medium. As Luca’s primary heir, Andrea learned not only sculptural principles of form and proportion from his uncle, but also the closely guarded technical procedures of glazed terracotta that made the family’s works exceptional in Renaissance Florence.

Throughout his long and prolific career, Andrea expanded and perfected the aesthetic, technical, and practical uses of tin-glazed clay sculpture. His terracotta works are recognizable for their highly refined modeling of serene faces and graceful drapery, their luminous surfaces, and their brilliant colors.

Although Luca and Andrea both carefully guarded their tin-glazing techniques, an early form of corporate espionage resulted in these methods being leaked, allowing competitors—such as Benedetto Buglioni, who crafted M&G’s Pair of Angels with Candlesticks—to share the profitability of glazed terracotta. Others, like Andrea’s son, Girolamo della Robbia, built on the families’ advances and developed firing processes needed for extremely large pieces, like M&G’s terracotta busts of French royalty.

Savonarola, a contemporary of Andrea, was a fiery preacher calling for reform within the Roman Catholic Church. He was not anti-art, but was critical of excessive ornamentation and sensuous beauty in religious art. He fostered art that reflected humility, repentance, and Christian devotion. There is documented evidence that contemporary Florentine artists such as Botticelli, were followers of Savonarola. Their works show dramatic stylistic shifts as Savonarola rose to prominence, as illustrated by M&G’s Botticelli tondo.

Art historians, including Sir John Pope-Hennessy and Franco Gentilini, have noted that Andrea’s later works resonate with what Savonarola described as “semplicità devota” (devout simplicity). Andrea increasingly favored simpler compositions and less exuberant ornamentation. His later images of the Virgin portray a quiet gravity rather than the courtly sweetness seen in both Luca’s works and Andrea’s earlier productions. There is no documentary evidence of a personal or ideological connection between Andrea and Savonarola; however, Andrea’s later works reflect the tone and purpose of the religious reform Savonarola advocated. One expert noted that M&G’s Sorrowing Virgin aligns not with Andrea’s early works, created under his uncle’s tutelage, but with those from his later period, “when he, himself was in control” of the studio.

The Same Molds

Andrea della Robbia’s wall-mounted glazed terracotta reliefs of the Virgin and Child were highly popular. The graceful, serene expression of the Virgin and the strong, confident appearance of the infant Christ reflect a devotional mood suitable for chapels, hospitals, orphanages, and private homes. These works also embody the “devout simplicity” endorsed by Savonarola.

While the background and frames vary considerably, the figures themselves were likely produced from the same molds. Minor variations can be as seen in details such as the Virgin’s head covering or placement of her right hand. Occasionally more significant variations occur, such as a swaddled Christ seated on His mother’s lap. These and other works that appear to derive from the same molds, can be found in situ in Italy, and in museums and private collections worldwide. Some have direct provenance to Andrea and his studio. A repeated detail also seen in M&G’s piece, is the decorative, single slipped reef knot on Mary’s belt, an Italian Renaissance symbol for purity.

M&G’s Sorrowing Virgin is unsigned; few Italian Renaissance terracotta pieces are, but some of the molds used to make Andrea’s wall-mounted reliefs of the Virgin and Child, as well as other works from his studio, appear to have been used in forming M&G’s piece. Experts agree that these and other similarities justify attributing M&G’s Sorrowing Virgin to Andrea and his studio.

M&G’s Sorrowing Virgin

The first known reference to M&G’s piece is in Allan Marquand’s 1922 Andrea Della Robbia and His Atelier. Marquand describes the sculpture, stating, “This much injured half figure of the Virgin is only partially glazed,” that in 1920 it was owned by the New York art dealership French & Co., and that it had received some conservation treatment.

It is possible that the piece experienced a kiln disaster during the firing to affix the glazes. Its extensive damage and conservation are in keeping with this scenario.

- The right side of the sculpture is glazed in standard colors for Renaissance terracotta. However, during conservation, areas not usually damaged by normal wear, received in-painting.

- The left side required extensive repair and was painted brown. It is unknown if any glazing survives beneath the paint.

- During the Renaissance, a permanent red glaze was impossible; artists often glazed areas brown and painted them red after firing. The Virgin’s dress is finished in a brown glaze, but the color intended for it is unknown.

- A firing problem could explain the very dark, unglazed terracotta of Mary’s face, neck, and hands.

The della Robbia studio developed skin-tone glazes, which Andrea used on works intended to be viewed from a distance. For more intimate sculptures, leaving the skin unglazed resulted in a pale brown, matte surface. Set against the high gloss of their glazed surroundings, these matte areas appeared as soft flesh. Unglazed clay also allowed for detailed modeling and subtle facial expressions, which would have been obscured by thick glaze. The expressions of the figures became the focal point of the sculpture. In keeping with Savonarola’s message, unglazed terracotta would convey the Virgin’s suffering more powerfully than a polished surface would.

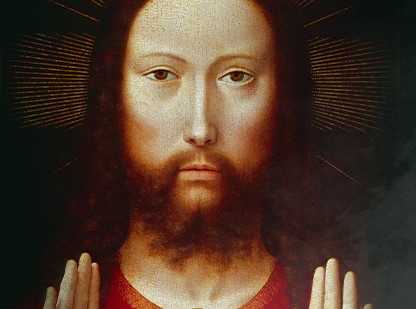

The Virgin Mary knew her Son, Jesus Christ, was the Messiah, the God-sent Redeemer. Her sorrow at His crucifixion stemmed from His unjust treatment and excruciating suffering. That sorrow would have been tempered by what the angel Gabriel had told her as His miraculous birth was described. He, the Son of God, would not only be her Redeemer, but He would also be an Everlasting King. Believing God, she had both hope and peace with her sorrow. All of which can be seen in the face of Andrea della Robbia’s Sorrowing Virgin.

William Pinkston, retired educator and M&G volunteer

Suggested References

Cambareri, Marietta. Della Robbia: Sculpting with Color in Renaissance Florence (Boston: MFA Publications, Museum of Fine Arts. Boston, MA. 2016)

Marquand, Allan. Andrea Della Robbia and His Atelier (Princeton University Press. Princeton, NJ. 1922)

Published 2026