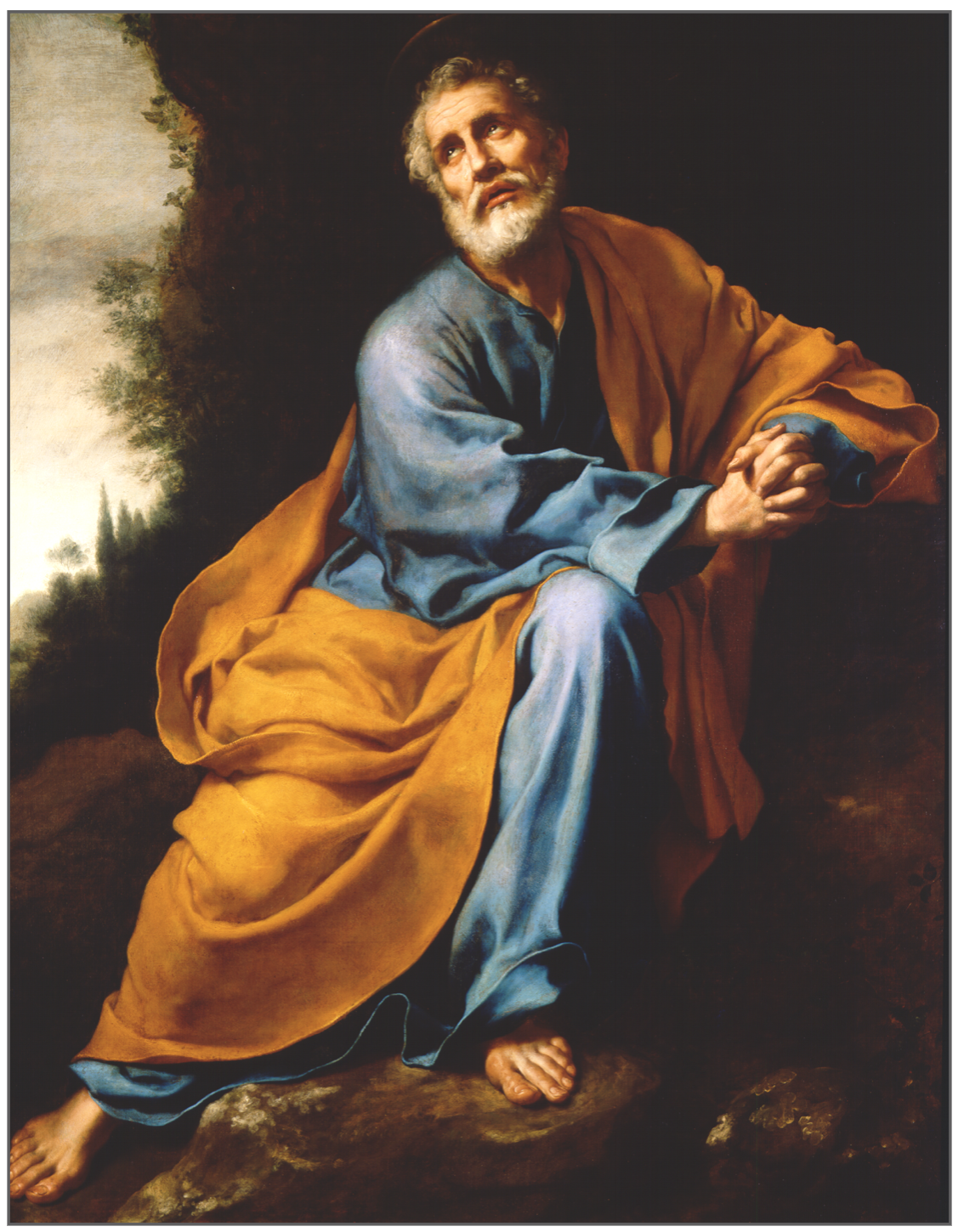

Vashti Refuses the King’s Summons

Oil on canvas

Edwin Long, R.A.

English, 1829-1891

Vashti showcases Edwin Long’s interest in archeological discovery, religious history, and female beauty on a grand scale, interests that reflect those of the Victorian era in which he lived. And the story of the two queens of Xerxes, king of Persia, is tailor made for both his interests and his skills. Like other religious painters of the era, such as William Holman Hunt, Long actually visited the Holy Land to gain firsthand knowledge. He combined this trip with various print sources such as volume III of George Rawlinson’s The Five Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World (1862-67) and Austen Henry Layard’s studies from Nineveh in order to create this painting of convincing Orientalism. Originally exhibited at Burlington House in 1879 with its companion piece, Queen Esther, the two paintings taken together (though not exhibited side by side) offer food for thought both on the characters of these impressive women and the critical period in which they lived.

Vashti opens the story of Esther with a dramatic refusal to appear at her husband’s banquet for the rulers of the Persian kingdom. Whether she refuses out of modesty (her crossed arms seem to support this position) or because she herself is hosting a banquet for the wives of the rulers, her refusal is seen as a harbinger of marital unrest in the kingdom if her disobedience goes unanswered. So the king is persuaded to depose her as queen and seek a new one. There are several indications that Vashti recognizes the serious implications of her rebellion. She is remonstrated by her maidens, there is an apparent altercation at the door between those delivering her refusal and those demanding her acquiescence, and her body language suggests that she is afraid of what is to come.

The symbolism so greatly loved by the Victorians comes into play through the great lion on which she sits. An emblem associated by the Persians with their great power, the lion reflects both the power that has made her queen and the power which she will be unable to thwart. Though the lion is itself slain and has lost its power over her, even serving as a bench cushion; one lone woman cannot stand against an Eastern potentate. Her name which means “Beautiful One” in Persian appropriately reflects her physical beauty, likely the avenue to her queenly position. However, beauty is hardly a weapon against the mighty Persians. Or is it?

Consider the story of Hadassah or Esther as most know her today. An entire book of the Bible, one in which there is no direct mention of Jehovah, chronicles a few brief years of a young Jewish maiden who had “come to the kingdom” (Esther 4:14) at a crucial time, not just as a result of the whim of the queen. Long means for viewers to examine these women in light of each other. A cursory glance reveals that the two paintings are meant as companions: the matching frames, the seated central figures, the inquisitive gaze and pose of the servant girl, the visible sandaled foot of both women. Even the “X” created by the arms of Vashti and the jewelry of Esther juxtapose these two women and their plights: one is apparently guarding her beauty from the ravaging eyes of the rulers, the other finds her beautiful figure emphasized in the king’s competition.

Consider the story of Hadassah or Esther as most know her today. An entire book of the Bible, one in which there is no direct mention of Jehovah, chronicles a few brief years of a young Jewish maiden who had “come to the kingdom” (Esther 4:14) at a crucial time, not just as a result of the whim of the queen. Long means for viewers to examine these women in light of each other. A cursory glance reveals that the two paintings are meant as companions: the matching frames, the seated central figures, the inquisitive gaze and pose of the servant girl, the visible sandaled foot of both women. Even the “X” created by the arms of Vashti and the jewelry of Esther juxtapose these two women and their plights: one is apparently guarding her beauty from the ravaging eyes of the rulers, the other finds her beautiful figure emphasized in the king’s competition.

Both women are “caught” by their positions though their gazes differ: Vashti’s gaze foreshadows her fall from favor while the frank gaze of the powerless girl (even her beauty is no match for an unextended scepter) foreshadows her strength of spirit. The adorned Esther has put down the mirror, rejecting the offer of more jewels. Instead, just prior to being veiled and taken to Xerxes, she looks directly at the viewer. This gaze, though solemn, reveals no fear in the innocent young girl (notice the lilies on the wall relief behind her) who by the next day will be either a mere concubine or the queen. The mythical griffins embroidered on the hem of her gown were figures used to guard the gold of the Persians and are another indication both of the marketplace contest she is part of and her inability to escape. Yet Esther has an inner strength that enables her to risk death at the hands of the king—in order to invite him to dinner!

Though Vashti is gone by the end of the first chapter of Esther, she begins the rising action of the story whose crisis is faced by her youthful successor. Without the brave action of Vashti, Esther would not have been in place to rescue her people. And without the brave action—and clever thinking—of Queen Esther, the Israelites would have lost their stand against the “divine” power (note the stylized sun on the end of the mirror handle and on Vashti’s belt) of the pagan Persians at the hands of Haman. If “the king’s heart is in the hand of the Lord” (Proverbs 21:1), it is certain the hearts of queens are as well. Edwin Long’s works draw attention to both the historical tensions in the Persian royal court and the metanarrative of the Israelites’ position as God’s chosen people.

Dr. Karen Rowe, M&G Board Member

Published in 2019