Salome with the Head of St. John the Baptist

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Below the image, click play to listen.

Oil on panel, monogrammed: D.F.

Dutch, 1498–1574

Maerten van Heemskerck was born the son of a farmer June 1498 in the Netherlands. He left the farm to study art under Cornelis Willemsz. in Haarlem and Jan Lucasz. in Delft. Between 1527-1530, Heemskerck placed himself under the tutelage of Jan van Scorel in Haarlem. M&G’s collection includes works by Scorel and Heemskerck’s biographer, Karl van Mander. Scorel had extensively studied in Utrecht (with Jan Gossaert), Germany (with Albrecht Durer), Switzerland, Venice, Jerusalem, Cyprus, Crete, and finally Rome. During his time in Rome, his artistic style was heavily influenced by the works of Michelangelo and Raphael. Scorel brought these new artistic ideas back with him to the Netherlands and taught them to Heemskerck.

Perhaps Scorel’s adventures inspired Heemskerck. Like many today in modern society, Heemskerck planned his own summer vacation. In 1532, he set off for an adventure with the primary purpose of seeing the Seven Wonders of the World. He left a parting gift for colleagues in the form of an altarpiece for St. Luke’s altar in Bavokerk depicting St. Luke painting Mary. He landed in Rome, July 1532. On his travels, he “made accurate, conscientious sketches of antique ruins and statues” (National Gallery of Art). He also was able to view for himself the works of Michelangelo and Raphael. In 1537, he returned to Haarlem where he remained for the rest of his life. He became well known for portraits, religious paintings, and producing designs for engravers.

M&G’s Jonah Under the Gourd Vine displays elements from Heemskerck’s travels. In the background behind Jonah, he includes the Vatican Obelisk as well as a bridge over the Tiber River which he probably saw during his time in Rome. In fact, the city of Nineveh looks more like the city of Rome than a city in the Middle East. Even the figure of Jonah mimics Michelangelo’s figures in The Creation of Adam. The whole composition imitates Heemskerck’s The Last Four Things as well as his Panorama with the Abduction of Helen Amidst the Wonders of the Ancient World.

Heemskerck depicts the portion of the story of Jonah where he has finally obeyed God’s call to preach repentance to the city of Nineveh. In Jonah 1:1, God commissioned Jonah to go to Nineveh and give the city a chance to turn from evil to God. However, Jonah thought that Nineveh deserved condemnation and judgment not mercy (Jonah 4: 2), so he attempted to run in the opposite direction toward Tarshish. Jonah’s disobedience resulted in his spending three days and three nights in the belly of fish before he repented, and God mercifully rescued him. Jonah now had a second chance to obey.

Jonah consented; he went and preached repentance to Nineveh. To his surprise, the whole city repented, including the king. Instead of rejoicing over those who repented, Jonah pouted in anger. Here Heemskerck portrays Jonah taking shelter under the leaves of a gourd vine overlooking the city of Nineveh with God looking down from the heavens. Trailing from his hand is a banner inscribed with BENE IRASCOR EGO VSQVE AD MORTEM IONA CA 4 16 which communicates Jonah’s true feelings: “Rightly I myself am exceedingly angry unto death, Jonah 4:16.” Having experienced God’s mercy first-hand and himself been given a second chance, Jonah should have delighted in God’s compassion. Sadly, he placed himself in the position of telling God what he believed God should have done—to pass judgment on the Ninevites. James 1:19-20 reminds us that unlike Jonah, we should follow God’s example and be “slow to wrath.”

Rebekah Cobb

M&G Collections Support Staff

Published 2023

Walnut and pastiglia

Italian, 15th century

The antique furnishings in the Museum & Gallery collection elevate each visitor’s experience of the artwork on the walls, but the pieces also provide a historical context of the eras and cultures from which the artworks sprang. Indeed, the furnishings are also artworks in themselves.

This is certainly true of the many cassoni (plural of the Italian term for “chests”) in the collection. Like other furnishings in Renaissance homes, the quality of workmanship and materials employed in decorating each cassone convey a great deal about the fashion of their times, the technologies available to craftsmen, and the wealth and social status of their owners.

Unfortunately, much has gone against their survival to our day. Cassoni were used for storage of personal items, opened and closed numerous times over the years. That wear, along with the environment in a home, infestations of termites, dry rot, changes in taste and reversals of family fortunes all conspire against the preservation of these furnishings.

These rich, showy Italian types of chests became widespread in Northern and Central Italy, particularly Tuscany (with a number of the best artists hailing from the cities of Siena and Florence). Weddings served as the occasions for which cassoni were made, and they were in fashion from the 14th-16th centuries, a period spanning the very late-Middle Ages to the beginning and middle of the Renaissance. The oldest surviving cassoni feature primitive panel designs, while later works demonstrate lavish carving, gilding, polychrome, and more complex narrative scenes.

Much like moving trucks, boxes, and barrels accompanying the establishment of new homes, cassoni had a very specific use. Practically speaking, the chests were designed to contain the bride’s dowry and jewels, her family’s contribution to the marriage, and became one of the couple’s most important household furnishings—often at the foot of the bed. They quite literally became a vehicle displaying the status, wealth and sophistication of the intermarrying families, carried in a procession (the domum ductio) from the bride’s parent’s home to her groom’s abode.

Decoratively speaking, cassoni often feature heraldic imagery relating to the families’ crests, and the pictorial panels often contained biblical, mythological, or allegorical imagery which ranged from learned and literary to humorous and light-hearted. Cassoni themselves were so common in the early- and middle-Renaissance that they’re included in Old Master paintings (most familiar may be scenes of the Annunciation in which Mary is seated on or kneeling near a cassone situated at the foot of her curtained bed) and even picture-within-picture vignettes on cassoni panels themselves.

This particular M&G cassone entered the collection in 1957, and its features suggest a date very early after 1400, likely from Tuscany. Unlike many cassoni today, which have the panels removed and presented as separate works of art in their own right, our chest is in good original condition and is structurally sound, despite surviving 600 years of use and change. The lid is still attached with its original hinges and has a simple locking mechanism. While the lid opens and closes easily, the tight fit and years of use have worn off some of the gesso along the top edge.

Composed of thick walnut planks and framing, the chest has a large front center panel decorated with gilt and polychrome over trellis-embossed gesso. Heraldic lions (possibly leopards or even hunting dogs) face each other across the front, and the two vertical end panels blossom with delicate arabesques and outline colored shields, which likely contained familial coats of arms.

Carved, fluted pilasters frame the two pictorial end panels and are topped with vague Corinthian capitals. The primitive-style narrative at the right end is now entirely obscured, but the imagery at the opposite end remains. The subject matter is indistinct and may be biblical or mythological. Most likely, perhaps, it is the myth of Diana (Artemis) and Actaeon, from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, in which the bathing goddess is startled by a young hunter. In her anger, Diana turns Actaeon into a stag who is then hunted and killed by his own hounds. This identification seems to make sense of the simplistic representation of forest, pool, a stag’s head (lower right) and a hound in the left background. As an allegory or fable for a young couple, it may emphasize modesty, self control, and consequences for the lack of either or both.

Carved, fluted pilasters frame the two pictorial end panels and are topped with vague Corinthian capitals. The primitive-style narrative at the right end is now entirely obscured, but the imagery at the opposite end remains. The subject matter is indistinct and may be biblical or mythological. Most likely, perhaps, it is the myth of Diana (Artemis) and Actaeon, from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, in which the bathing goddess is startled by a young hunter. In her anger, Diana turns Actaeon into a stag who is then hunted and killed by his own hounds. This identification seems to make sense of the simplistic representation of forest, pool, a stag’s head (lower right) and a hound in the left background. As an allegory or fable for a young couple, it may emphasize modesty, self control, and consequences for the lack of either or both.

This cassone provides insight into the artistry, fashion, and domestic life of those living in the early years of the Italian Renaissance and is a valuable part of the M&G collection.

Dr. Stephen B. Jones, M&G volunteer

Additional Resources:

The Oxford History of Western Art. Kemp, Martin, ed. Oxford University Press, 2000.

Pooley, Eugene. “Scenes from a Marriage.”

https://blog.dorotheum.com/en/classic-week-florentine-school/

https://www.medieval.eu/bridal-chests-or-cassoni-from-medieval-italy/

Published 2023

Francesco Granacci’s Rest on the Flight into Egypt is an excellent example of the High Renaissance style.

The Della Robbia family is famous—for their secret artistic recipe. Watch to learn more about a pair of sculpture and this family of artists represented in M&G’s collection.

The European furniture in the Museum & Gallery collection has been called the finest in America by Joseph Aronson, author of The Encyclopedia of Furniture. This beautiful Italian cassone is a good example.

In this triptych the artist beautifully pictures several of the most familiar Christmas story events.

Oil on panel

German, active c. 1485–1515

Click on the links throughout the article to view additional artists’ works and reference material.

Little background history exists for the artist referred to as the Master of St. Severin. While scholars remain uncertain as to his identity, they have confidently identified a body of works they believe to be by his hand. The Church of St. Severin houses what are considered his best works, thus he became known by the pseudonym, the Master of St. Severin. His body of work primarily reflects oil paintings on panel, however, there is some indication that he might have also designed and produced stained glass windows.

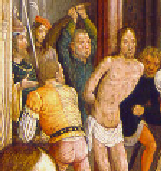

Christ before Pilate brings together several of the events of the Passion Week leading to the crucifixion of Christ. He did a similar work called Passion Scene: Christ at the Mount of Olives. Both works embody his style evidenced in the stiffness of the figures and the similarity in facial features and expressions of all figures. In the foreground of M&G’s work, a solemn and calm Christ appears before Pilate for trial. The surrounding miniature scenes reveal the events preceding and following his trial. To the left in the distant background, the artist portrays Christ’s prayer and arrest in the Garden of Gethsemane along with Peter cutting off Malchus’ ear. Centrally located in the background and enclosed in a cathedral-like structure, Christ receives beating with the cat of nine tails and then just below He is crowned with a ring of thorns. Finally, to the far back right, Pilate presents Christ to the Jews.

Beautifully detailed in oil, the painting provides a window into the culture of the artist. Click the dropdown below to learn more about the clothing featured by the Master of St. Severin.

Dagging is cutting the edges of garments, hangi ng sleeve flaps, or even hats into pointed or squared scallops. This trend was especially popular during the late Middle Ages. The man in red at Christ’s crowning with thorns features dagging at the bottom of his doublet (jacket).

ng sleeve flaps, or even hats into pointed or squared scallops. This trend was especially popular during the late Middle Ages. The man in red at Christ’s crowning with thorns features dagging at the bottom of his doublet (jacket).

Also known as crakowes, these were an elongated, exaggeratedly pointed-toed shoe often worn by nobles or the wealthy. King Edward III  tried to take matters into his own hands by declaring a law that “no Knight under the estate of a lord, esquire or gentleman, nor any other person, shall wear any shoes or boots having spikes or points exceeding the length of two inches, under the forfeiture of forty pence.” The law was ineffective, and the trend lasted until 1480! The man, at right foreground and near to Pilate, models poulaines.

tried to take matters into his own hands by declaring a law that “no Knight under the estate of a lord, esquire or gentleman, nor any other person, shall wear any shoes or boots having spikes or points exceeding the length of two inches, under the forfeiture of forty pence.” The law was ineffective, and the trend lasted until 1480! The man, at right foreground and near to Pilate, models poulaines.

These were a special non-functional, decorative sleeve attached to the jacket; in the early Renaissance, they were mostly us ed for ceremonial occasions as seen here on the soldier kneeling in the foreground.

ed for ceremonial occasions as seen here on the soldier kneeling in the foreground.

Parti-colored is the sewing together sections of different colored fabrics within the same garment. This was used in both men’s and women’s clothing and could reflect the colors of a particular city or families joined in marriage. The man kneeling in front of Christ at his crowning with t horns features

horns features a parti-colored doublet. At the beating of Christ, the man to the left of Christ also wears a parti-colored doublet.

a parti-colored doublet. At the beating of Christ, the man to the left of Christ also wears a parti-colored doublet.

Rebekah Cobb, Guest Relations Manager

Published in 2017