Casket

Bovine Bone

Flanders, 15th century

Acquired with funds from the Audrey Love Charitable Foundation

Click on the links throughout the article to view additional artists’ works and reference material.

Special boxes or caskets were once made to hold valuable items or at least the personal items of the wealthy. These containers, used for storage and transport, are often beautifully decorated and constructed of rich materials themselves—a practice that has existed for centuries as far back as Egyptian culture.

Many of the surviving caskets focus on romance—decorated with scenes from medieval literature including Tristan, Taking the Castle of Love, Aristotle’s infatuation with Phyllis, poems by Homer, and the concept of chivalry in the characters of Sir Gawain, Lancelot, Percival and others. Thomas T. Hoopes, former curator at the MET explained, “In nearly every case they are decorated with scenes from popular legend and romance, especially with such as would have an allegorical significance appropriate to the occasion for which they were designed.”

In the middle ages, France was the primary creator and market for the luxury items of carved ivory and bone, but by the fifteenth century the center of industry shifted. The best known craftsmen were the and Florence. For four decades, this group of artisans created and satisfied the demands of fashion crafting beautiful objects in ivory, wood, bone, and horn. The workshop produced a variety of carvings including large and small altarpieces, but their principal output seemed to focus on special, personal items such as caskets, mirror cases, and small toilet articles—many of them bridal gifts or gift sets for the wealthy and noble of the court.

However, the Embriachi weren’t the only entrepreneurs in carving; the industrious and creative Dutch also continued the French tradition. The workshops in both the southern and northern Netherlands innovated and developed commercial centers for a variety of products including textiles, metalwork, and oil painting. Specifically, the workshops in Flanders developed an export trade of bone boxes and ivory products that traversed the Rhine river routes to European cities and markets—bone boxes like the present Casket.

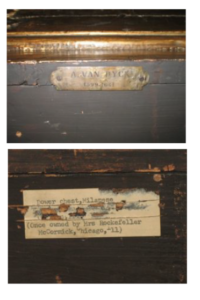

M&G displays a number of cassone and chests used by our European forbears to store their household items as well as a few smaller versions of storage containers in the form of coffers and now a casket for protecting one’s precious personal items: jewelry, documents, and sentimental objects.

At one time, it was the height of medieval fashion to own a casket, but with the delicate nature of the material it is unusual to have an intact box that has survived time, use, and past repairs.

The Casket is constructed of bovine bone mounted on a wood structure. The bottom of the box is a checkerboard pattern of wood and bone, and the sides and top are carved in low relief, which still retain some gilding and color. The carved decoration is religious depicting Christ, apostles such as Peter holding the keys, and various saints including St. Catherine identified by her wheel. Perhaps the religious decoration on its exterior reveals that this Casket formerly sheltered a manuscript or religious text.

Since the background of the individual bone plaques is crosshatched, it may indicate that the workshop was influenced by religious prints and engravings from the time period, such as Biblia Pauperum (the Pauper’s Bible).

While the interior is lined by worn and repaired green fabric, interestingly, what was so valued to be safely stored inside is now lost. Once an expensive, beautiful container for holding something of great value, however, it is now the container itself that has become the treasure.

M&G is grateful for the generosity of the Audrey Love Charitable Foundation, without whom we could not have acquired this beautiful, mysterious medieval object.

Erin R. Jones, Executive Director

Published in 2016