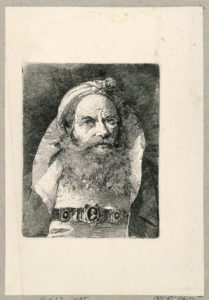

The Return from the Flight into Egypt

Oil on canvas, c. 1712

Giuseppe Bartolomeo Chiari

Roman, 1654-1727

Rome was for centuries the epicenter of culture, art, and religion. At the time of Giuseppe Chiari’s birth, it was also “the scene of a lively debate with a constantly varying interplay of influences, trends, fashions, specialized treatises, and, of course, great masterpieces” (Zuffi, p. 64). At the center of this debate were three artistic movements that Zuffi notes “succeeded one another in a sort of ideal relay race of artistic styles.” The stark naturalism of Caravaggio, the elegant classicism of Annibale Carracci, and the dramatic baroque sculptures and architecture of Gian Lorenzo Bernini would all play a part in making 17th-century Rome—well, Rome!

As president of the Roman Academy Carlo Maratta was keenly aware of these lively debates. Considered one of the most important painters in the latter half of the 17th century, he was much admired for his beautiful frescos and stunning portraits. Although his work evidenced a clear admiration for the classical tradition, several of his paintings also integrated elements of Caravaggio’s vigorous style. David Steel points out that Maratta often “managed to steer a middle course between these two dominant and often contrary trends of baroque painting” (Steel, p. 88).

Maratta was at the summit of his career in 1666 when 12-year-old Giuseppe Chiari entered the great master’s studio. Chiari soon became a star pupil. Over the years, his profound respect for Maratta’s tutelage would not only shape his artistic development but also ensure his future success in a highly competitive environment. When Maratta died in 1713, Chiari took up Maratta’s mantle and became the dominant Roman artist.

Like Maratta, Chiari broadened his appeal by becoming an astute observer and deft practitioner of integrating stylistic trends. Kathrine and William Wallace highlight this skill in their comparative analysis of Chiari’s Tedallini altarpiece with Caravaggio’s Madonna dei Pellegrini [figs. 1 and 2]:

“The statuesque pose of Chiari’s Madonna, the unusually high step on which she stands, the elongated form of the Christ child framed by a white swaddling cloth, and the overall right-triangular composition recall Caravaggio’s Madonna dei Pellegrini. Yet the suggestion is subtle: Chiari has reversed the composition, naturalized the pose of the Virgin, and substituted the more palatable, well-dressed saints for the dirty feet and common character of Caravaggio’s pilgrims. Although inspired by Caravaggio, Chiari’s altarpiece remains distinctly his own. Chiari’s Madonna looks like a person of warm flesh and blood rather than the marmoreal statue of Caravaggio’s Madonna; Christ is an attractive child of sweet disposition as opposed to the enormous and ungainly figure depicted by the older master. Instead of the muted and earthy colors of the Madonna dei Pellegrini, Chiari’s bright hues are immediately pleasing and a welcome contrast to the comparatively dark paintings found on so many Roman altars” (p. 4).

The Return from the Flight into Egypt provides another example of Chiari’s virtuosity and unique style. Here, however, he turns from echoing the past to adumbrating the future. The refined handling of the paint and elegant figural poses pay homage to the classical tradition; however, the playfulness, delicate coloration, and ornamental enrichment mark the transition into the sensuous, intimate style of the rococo movement which emerged in France and spread throughout Europe in the 18th century (Chilvers, 507).

M&G has two works by Chiari on this subject, one titled The Rest on the Flight into Egypt and this rendering titled The Return from the Flight into Egypt. Over the years scholars have found the less traditional title of this 1712 work problematic. However, “the light-hearted, almost celebratory mood” (echoed in the Rococo style) reinforce the idea that here, Chiari intends to highlight the family’s return from rather than flight into Egypt. Regardless of the debate, art experts like Christopher Johns note that this picture may be the best example of Chiari’s work in America.

Donnalynn Hess, M&G Director of Education

Resources:

Baroque Paintings from the Bob Jones University Collection by David H. Steel

Concise Dictionary of Art and Artists, 3rd edition by Ian Chilvers

“Giuseppe Bartolomeo Chiari,” The Art Bulletin, March, 1968, Vol. 50, No. 1 by Bernhard Kerber and Franciscono Renate

“Seeing Chiari Clearly,” Artibus Et Historiae, 2012, Vol. 33, No. 66 by Katherine M. Wallace and William Wallace

Published 2024