Torah Case

Torah Mantle

Torah Finger

From the Bowen Collection of Antiquities

The Torah contains the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Old Testament) divided into 54 sections. These portions are read out loud to Jewish congregations throughout the year in the synagogue, at ceremonies (like weddings, funerals, and Bar Mitzvahs), and at commemorative events in the Jewish calendar. But only a Sefer Torah (one that is approved and ritually clean) can be used in public Jewish worship.

Jewish tradition holds that the very words of the Pentateuch were dictated by God, and thus, are worthy of the extreme care given to ensure that all the 304,805 Hebrew letters in the Pentateuch have been accurately hand copied in a Sefer Torah. To make certain that nothing detracts from the words, only specific fonts are used, and embellishment or illumination of the text is prohibited. However, to show respect for a Sefer Torah and to reflect its value to congregants, the objects associated with it are often lavishly ornamented.

Torah Case: Tik

The Aron Kodesh (the “Torah ark” or “ark”) is the focal point in a synagogue. Depending on the means of the congregation, the ark may be a simple wooden cabinet or a large structure adorned with ornate carvings and precious materials. When the Aron Kodesh is opened the true valuables of the synagogue—its Sefer Torahs and items associated with their use—are revealed.

Generally, Sephardic Jews keep a Torah scroll in a cylindrical case, called the tik, which holds the scroll upright. M&G’s Torah Case (tik) is a wooden, hinged cylinder covered in fabric and embellished with embossed silver appliqués. The top, decorative portion of the tik is called the Torah crown. M&G’s Torah crown appears to be a modified pomegranate shape. Since God instructed the Jews to use pomegranate motifs on the High Priest’s ceremonial garments, and they were also used to ornament the Tabernacle and Solomonic Temple, modified pomegranates are traditional tik adornments.

On chains from M&G’s Torah crown are tiny bells which would tinkle as the tik was carried from the ark to the bimah, the place in the synagogue where the tik would be opened and the Torah read. However, missing from M&G’s tik are two rimonim (Hebrew word for pomegranate); these decorated finials fit on the rods on top of the tik and serve as handles for opening the scroll. When the tik was fully open on the platform, the scroll (also missing from M&G’s tik) would be upright and a column of the Torah’s text would be visible for the reader.

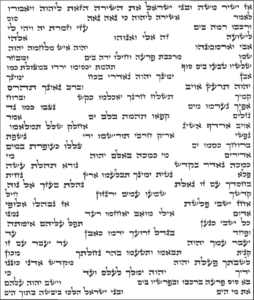

The picture on the right highlights additional interesting details. For example, the inscription in the upper left reads: “This case of the Scroll of the Law was made by the good woman, the daughter of Meir Zekiel Samuel.” The inscription in the upper right reads: “This is the Law which Moses set before the children of Israel. These are the testimonies, the statues, the ordinances, etc.”

Torah Mantle

Ashkenazic Jews generally store Torah scrolls in mantles that have openings at the top to accommodate the handles of the atzei chayim (the “trees of life”), which are the wooden dowels on which the scroll is rolled. Torah mantles take various forms and can be made of simple cloth, rich brocades, or velvet. They are frequently embellished with elaborate embroidery and appliqué.

M&G’s Torah Mantle is maroon velvet embroidered with the tablets of the 10 commandments, the lion of the tribe of Judah, and crowns representing the Jewish kingdom. Other common mantle motifs include the tree of life, the star of David, pillars of the temple and the seven-branched menorah. Once an Ashkenazi Torah is carried to the bimah (platform or podium), the mantle is removed and depending upon local traditions, the Torah is either laid flat or supported on an incline before being read publicly.

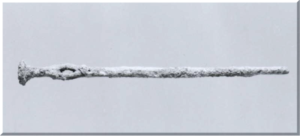

Torah Finger: Yad

The actual writing of a Sefer Torah should not be touched. Not only would it be disrespectful to the words of God, the perspiration and oils from the hand could lead to deterioration and flaking of the ink. Damage to a Torah causes it to no longer be Sefer and thus unusable in Jewish public worship.

To read passages of the Torah during a service is an honor, but keeping one’s place during public oral reading is not always easy. To help prevent mistakes, a yad (sometimes called a Torah finger) is used. Yads often have a handle, a shaft, and a hand with a pointing finger. Some have chains used to hang them on the scroll when stored in the Aron Kodesh. A yad is often made of gold, silver, wood, bone or, like M&G’s Torah Finger, bronze. The person reading may follow the text with the yad, or another person may use the yad to indicate the text to be read.

The extreme care exercised when preserving the text of the Torah and the lavishness of the trappings which adorn the Torah give witness to the reverence the Jewish nation has for the words of God.

William Pinkston, retired educator and M&G volunteer

Selected References

Baghdadi Torah Case (Tik): This gallery section shows the scroll within the Torah case.

Jewish Virtual Library: Torah Ornaments

Jewish Virtual Library: Ark

Why Do Sephardim Keep Their Torahs in Cylindrical Cases?

Published in 2021

ive Committee. He pointed out that a collection of sacred art would be an excellent complement to the schools of Fine Arts and Religion. The Executive Committee agreed, established an acquisition fund, and empowered Dr. Bob to begin collecting art for the university. The criteria for collecting were determined, since every collection must establish its boundaries in order to create its own unique and useful niche: it would be limited to western religious art.

ive Committee. He pointed out that a collection of sacred art would be an excellent complement to the schools of Fine Arts and Religion. The Executive Committee agreed, established an acquisition fund, and empowered Dr. Bob to begin collecting art for the university. The criteria for collecting were determined, since every collection must establish its boundaries in order to create its own unique and useful niche: it would be limited to western religious art. time of development, the Gallery also acquired the James Cole Collection of Ecclesiastical Textiles and Vestments, and began acquiring valuable furniture and the

time of development, the Gallery also acquired the James Cole Collection of Ecclesiastical Textiles and Vestments, and began acquiring valuable furniture and the