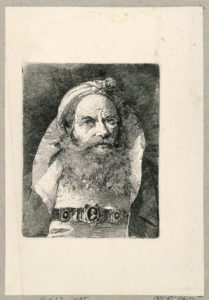

Meissen Vase

Porcelain, Mid-19th century

Ernst August Leuteritz

German, 1818 – 1893

Augustus II was elector of Saxony, King of Poland, and Grand Duke of Lithuania. In the early 1700s he established Saxony as one of the most economically advanced areas of Europe and built himself a magnificent residence in Dresden where he maintained a lavish court. He was obsessed with the highly fashionable porcelain pieces imported from China and had a large collection of “white gold” (an appropriate name, for some of the more desirable pieces of Chinese porcelain were virtually worth their weight in gold). His collection not only impressed guests, it depleted his treasury. He was in constant need of the metallic variety of gold.

About 1700 in Prussia, a bright young apothecary’s apprentice, Johann Böttger, was bragging that he had found the goldmachertinktur (translation: gold maker tincture), a concoction that could convert base metals into gold. In an attempt to put the lad in his place, the apothecary asked Böttger to demonstrate the transmutation. The procedure was done under close supervision, and it worked! It produced several ounces of highly refined gold. (Böttger never revealed how he performed the trick, nor was it ever repeated.) The Prussian king learned of the success at making gold and seeing a way to fill his treasury, had Böttger put in “protective custody.” Knowing what happened to alchemists who failed to produce gold for their royal masters, Böttger panicked, escaped, and fled.

Böttger made it to Saxony. There his Prussian pursuers would not have authority to apprehend him. However, Augustus II learned of Böttger’s transmutation and had him captured and placed in a dungeon-like, medieval fortress. He could purchase his freedom with gold. Eventually the quantity demanded would not only fill the treasury, but also add some significant white gold pieces to Augustus’ collection. At one point Augustus even alerted the mint to be ready to strike coins with the gold that would soon be arriving. It never came.

Ehrenfried von Tschirnhaus, an educated German mathematician and scientist, was trying to make porcelain by heating various white materials to high temperatures. His experiments either failed or made a type of glass. Since Böttger did not seem to be progressing in producing a goldmachertinktur, Augustus hired Tschirnhaus to supervise Böttger’s work. Originally Böttger looked down on Tschirnhaus’ experiments but realizing that perhaps white gold might spare his life, Böttger took interest in Tschirnhaus’ work.

A white clay mined near Meissen, a small town 16 miles from Dresden, contained kaolin and when mixed with various other materials, produced porcelain. Experimentation refined the recipe and eventually a porcelain equal to that imported from China, was made.

Augusts named Tschirnhaus director of the porcelain factory he planned to establish in Meissen. The white clay mines were nearby, and Meissen was on a major river so the wood needed for the kilns could be easily delivered. In 1708, before the factory could be built, Tschimhaus died suddenly. A few months later Böttger was named head of the Saxon Royal Porcelain Manufactory, the first factory to produce hard-paste porcelain in Europe.

Sculptors were hired to mimic the shapes of oriental pieces, and chemists were brought in to develop colored and clear glazes. The Meissen manufactory, as it came to be known, became highly profitable. Böttger’s living conditions greatly improved, but he did not completely regain his freedom. He remained director of Augustus’ manufactory until his death in 1719.

In the following 300 years, the Meissen manufactory constantly produced porcelain pieces. Sometimes the company was well managed and produced high quality, fashionable, and much sought after works. At other times, Meissen struggled under a variety of challenges including contaminants in the clay, export tariffs, limited production, outdated designs, and political turmoil (such as Napoleon and, later Hitler). Once Sèvres in France and both Minton and Wedgewood in England perfected porcelain production, Meissen’s bottom line suffered.

As mass manufacturing methods of porcelain and decoration became perfected, Meissen faced a decision: use modern methods to produce quantities of inexpensive pieces or continue with handcrafted and hand painted pieces. The company decided to produce only high quality, handmade and hand-decorated pieces. Present day Meissen pieces can be as valuable as the very old ones.

Ernst August Leuteritz and M&G’s Schlangenhenkelvase

Ernst August Leuteritz was born in Fischergasse (city near Meissen) in 1818 and became an apprentice in the Meissen manufactory at 18 years of age. He immediately demonstrated exceptional abilities in modeling and embossing. The next year he was given a stipend for a year’s leave of absence to study under Rietschels at the Art Academy in Dresden. Being very timid, he found the experience extremely difficult and returned to Meissen after a short stay; however, he was convinced to complete his training. His artistic growth and refinement of skills led Meissen to extend his leave for further studies. After several years he returned to the manufactory and was promoted to the position of “Modeler.” In 1849 he became Meissen’s “Head of Design,” a position he held until his retirement in 1886. He died in 1893.

During his tenure with Meissen, Leuteritz designed hundreds of ornate figurines, centerpieces, candlesticks, serving dishes, vases and virtually every other type of porcelain piece imaginable. Today his works are found in many museums and personal collections and fetch high prices at auctions.

Leuteritz designed several vases adorned with serpents. In 1853 he designed the schlangenhenkelvase (translation: snake-handled vase) in M&G’s collection. It is an amphora shaped vase on an ornately-sculpted, round pedestal. On each side a pair of snakes emerge from acanthus leaves, forming a loop and resting their heads on the rim. The schlangenhenkelvase in M&G’s collection was very popular in the second half of the 19th century and came in different sizes. M&G’s vase is 19 inches high and 13 inches wide.

The body of M&G’s vase is a deep garnet with accents of gold and white. The gold on the leaves and snakes appears worn in areas. The vase, however, still maintains its original gold application.

The Meissen Hallmark

The secret formula for making porcelain was protected by Meissen, until it was leaked to Austria through corporate espionage. By 1717, a factory in Vienna began producing porcelain; and by 1760, there were thirty European porcelain manufactories. In order to identify Meissen pieces, blue underglaze markings were added.

By 1720, the crossed swords from the Elector of Saxony’s coat of arms were introduced and by official decree in 1731, was required to appear on all Meissen porcelain. Meissen’s crossed-swords logo is among the oldest and longest used trademarks, as well as being among the most often forged. Variations of the sword’s curvature, hilt placement as well as other embellishments help to date the pieces. Since the hallmark was hand painted, there is considerable variety even among authentic logos.

By 1720, the crossed swords from the Elector of Saxony’s coat of arms were introduced and by official decree in 1731, was required to appear on all Meissen porcelain. Meissen’s crossed-swords logo is among the oldest and longest used trademarks, as well as being among the most often forged. Variations of the sword’s curvature, hilt placement as well as other embellishments help to date the pieces. Since the hallmark was hand painted, there is considerable variety even among authentic logos.

Under the base of M&G’s schlangenhenkelvase is the blue underglaze Meissen crossed-sword logo. Experts recognize it as genuine. The mark indicates that this vase was possibly made in the late 19th or first quarter of the 20th century. The underglaze “67” identifies the garnet painter, and the gold “2” indicates either the painter of the gold or that M&G’s vase may be one of a set.

Now the good news: you can have your own authentic schlangenhenkelvase without having to search the internet or attend an art auction where fake vases have been known to exist. Meissen still manufactures schlangenhenkelvase as part of their Masterworks Collection. They are not stock items; each one is produced to order and includes hand painted floral bouquets on the amphora. View the strikingly beautiful vase you could own by clicking on the Purchase a Vase link below. However, be prepared for a bit of a shock.

William Pinkston, Retired Educator and M&G volunteer

References

Video of the discovery of how to manufacture porcelain

Video of Meissen manufacture of porcelain, including a schlangenhenkelvase being painted

Meissen Museum

Purchase a Vase

The Book of Meissen (Schiffer Book for Collectors) by Robert D. Rontgen

Meissen Porcelain Identification and Value Guide by Jim and Susan Harran

Published 2024