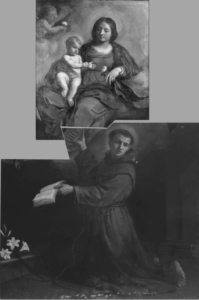

This work by an unknown 17th-century Italian painter beautifully unfolds the message of unmerited grace offered to mankind by a holy God.

Tag Archives: 17th century

Sea Captain’s Chest

Oak, Initialed and Dated: 1614

Dutch, 17th century

The Museum & Gallery’s renowned collection of art reflects timeless Truth communicated over centuries of storytelling by the most notable artists of their day. These artists sought to share transcendent spiritual realities, but each was limited to the historical “palette” available to them—levels of biblical understanding, historical and geographical knowledge, national boundaries and cultural context. While studying the artworks, we also learn of the cultural landscape of their time.

In a way that is unique in the art world, the Museum & Gallery’s important “canvasses” are not just on the walls. The nearly 150 pieces of medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque furniture expand our knowledge of the eras in which they were made and the distinctive purposes for which they were created.

Take for instance this Dutch Sea Captain’s Chest. Made from dense, rot-resistant Northern European oak, constructed with sides that splay outward as they rise toward the domed lid (in order to fit against a ship’s interior hull) and including a second, smaller compartment inside, the chest is bound with thin iron strapwork that serves as structural reinforcement, security, and decorative purposes. Engraved on the substantial lock are the year (1614), month (December) and initials of its maker or owner (CNDE). While most sailors had a small, simple sea chest, a captain’s sea chest would reflect the greater size of his responsibility, his social position, and the types of things that would be needed during an 8–10-month voyage (charts and maps, important trade documents, the sailors’ pay, and personal possessions). Such chests were a necessity, but they also came to be artworks in their own right.

This M&G chest hails from the Dutch Golden Age, which extended from the 17th through the early 18th centuries. This era witnessed an explosion of Dutch arts, trade, wealth and world standing. Rembrandt (1606-1660) and Vermeer (1632-1675) both lived in the 1600s, and they recorded the wealth and complexity of their society. Many of their patrons and subjects were astoundingly wealthy noblemen and merchants. None of this would have been possible without Dutch sea trade and the ships’ captains, who facilitated it.

The main engine of Holland’s wealth and global importance was the Dutch East India Company (or Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, VOC). Founded in 1602 and liquidated in 1795, the VOC was the most significant of the early European trading companies operating in Asia, and a little background is in order.

In 1579 the Treaty of Utrecht united the Low Countries (the seven northern provinces) in their struggle for independence from the Spanish/Hapsburg rule, forming what would become the Republic of the United Netherlands. Even before this union the mariners and merchants of these provinces were the most prolific and successful in the region. In 1599, likely using information gained through espionage, the first Dutch fleet attempted to break Portugal’s monopoly of the Asian spice trade. The endeavor was only mildly successful financially, but it showed what might be done.

By 1602, so many Dutch companies were competing for the spice trade that the price and glut of spices in Europe became an issue. In a single act of fiat, the Dutch government amalgamated these companies into a single entity, the United Dutch East India Company. The government gave the company a monopoly on the spice trade via the Cape of Good Hope, and it would become a behemoth.

By the middle of the 1600s the Dutch East India Company would own 150 ships, have 50,000 employees worldwide, field a private army of 10,000 soldiers, and maintain outposts from the Persian Gulf to Japan. This, the world’s first truly multinational company, had the right to wage war, create new colonies, make treaties, punish and execute criminals, and coin its own money. Between 1602 and 1796—a time when a round-trip voyage from Amsterdam to Jakarta required at least 8-10 months—the Dutch East India Company conducted more than 5,000 voyages between Holland and Asia.

In a single object, M&G’s Dutch Sea Captain’s Chest embodies a Golden Age of art, exploration, and trade. Similar chests would have been familiar to Rembrandt, Hals and Vermeer, and it’s fitting to have such a chest in the Collection. If we listen, they illumine us about both their own cultural moment and the influence that culture continues to have upon the world as we know it.

Dr. Stephen B. Jones, M&G volunteer

Resources:

Published 2025