St. Nicholas, the Wonderworker

Moscow School

Below the image, click play to listen.

In 2015, M&G produced a series titled Love to Learn Cafe which allowed educators to share a favorite subject. English professor, Dr. Rhonda Galloway chose the Brownings–two Victorian poets whose love story is almost as famous as their poetry. In Part 1, she explores Elizabeth’s background.

Watch Part 2 HERE.

In Part 2 (of 2 segments), Dr. Rhonda Galloway continues by introducing Robert Browning and highlighting how his courtship with Elizabeth began–a courtship that grew into a celebrated love story and a happy marriage.

Go back to Part 1 HERE.

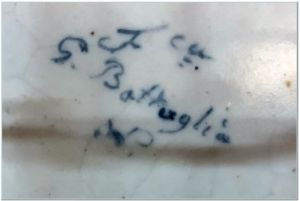

Glazed earthenware, signed G. Battaglia

Italian, c. 1826-1887

Majolica is earthenware that has been fired in a kiln, coated with an opaque white glaze, decorated with other pigments and fired again, fixing the glaze and design onto the ceramic. The process originated in Africa around the 6th century. By the 13th century, techniques and the ability to paint detailed designs were perfected. It was discovered that a clear glaze and a third firing added luster to the piece.

Italians became enamored of these decorative ceramics. Large quantities were produced in Africa and Spain and passed through ports on the Spanish island of Majorca on their way to Italy. Thinking the pieces had been made there, Italians called this kind of ceramic majolica or maiolica.

By the Italian Renaissance, techniques for producing majolica ceramics had reached Italy. Ceramists produced decorated plates, jars, cups, pitchers, and ornamental pieces. Often the item featured a portrait of a bride, a family member or some notable. Apothecary jars bearing the name of their contents were embellished with scrolling vines, leaves, flowers, and fruits. Wealthy families would display large sets of dishes and serving pieces which were used to impress guests at elaborate banquets.

Often these pieces were istoriato, meaning they illustrated a story—usually mythological, historic, or biblical. Sometimes the narrative would cover the entire surface of the piece; other times, as seen on M&G’s charger, the picture would be surrounded by intricately designed borders. Today museums and collectors prize even the broken pieces of Italian Renaissance majolica.

Although it may look it, M&G’s Majolica Charger is not dated to the Italian Renaissance. In the late 1800s, there was a resurgence of interest in the Italian Renaissance ceramic design, and Italian ceramists produced high quality stoneware in the Renaissance style to meet the demand. M&G’s charger is one such piece.

Making Majolica

Creating an elaborate majolica requires great skill. Not only must the clay be formed and fired carefully, but the tin oxide glaze which dries into an opaque, white surface must also be evenly applied. Colored glazes are then painted onto the prepared surface. The color palette is extremely limited. Black, yellow, blue, golden brown, and green were used on M&G’s charger—typical of majolica designs. Diluting, concentrating, or mixing the glaze pigments can produce various shades of colors.

Painting on the porous white surface is extremely unforgiving. Once applied, the pigment cannot be removed or hidden by painting over it. Adding pigment to the initial layer produces different effects; however, the original brush stroke, as well as any additional painted strokes and colors in subsequent layers must be adeptly applied. There is no way to repair a mistake.

Consider the border on the lip of M&G’s charger. The inner ring consists of an amber background with 50 hand-drawn, double circles of two different intensities of a golden-brown pigment. The outer border contains 8 fauns, 4 winged angel heads, and 4 angel torsos arranged among scrolling foliage and architectural flourishes. These are arranged in four matching quadrants. The figures are outlined in black and shaded with gray. After the black outlines were painted, the intense blue background areas were painted individually. The lip alone required a precise, highly skilled artisan.

Gaetano Battaglia

Painters of istoriato majolica scenes were consummate craftsmen, such as Gaetano Battaglia (c. 1826-1887). During his lifetime he was known as “a painter of figures.” His exquisite work, often large ceramics with Battaglia’s signature, are in museums and private collections.

His career started around 1850 in Naples, Italy, but little is known of his early works or employment. When the Mosca brothers founded Raffaele Mosca & Compagno in 1865, they hired Battaglia, and he helped them hire other ceramic painters. During the company’s more than 40-year history, its name and ownership repeatedly changed. Mosca produced architectural ceramics and decorative pieces, and it was known for producing an “odorless toilet,” patented by one of the brothers. Battaglia’s duration at the firm, however, is unknown.

Most ceramic painters of the period did not (or were not permitted to) sign their pieces. While many works are attributed to Battaglia, most earthenware known to be his are inscribed with his signature or initials. Generally, his signature is paired with the letter “N” or with “Napoli” for Naples. M&G’s Majolica Charger bears both Battaglia’s signature and an “N” on the reverse.

Most ceramic painters of the period did not (or were not permitted to) sign their pieces. While many works are attributed to Battaglia, most earthenware known to be his are inscribed with his signature or initials. Generally, his signature is paired with the letter “N” or with “Napoli” for Naples. M&G’s Majolica Charger bears both Battaglia’s signature and an “N” on the reverse.

The specific company that produced many of Battaglia’s signed pieces, however, is unknown. The “Fca” on M&G’s charger (which appears as “Fabb” on other Battaglia pieces) presumably stands for Fabbrica, Italian for “factory.” At that time there were numerous ceramic companies in Naples which had Fabbrica as part of their name. Battaglia may have worked for one of those companies or fired his earthenware designs in a hired kiln, which was a known practice at the time.

The Image

For istoriato earthenware, ceramists in the 1800s often referenced narrative etchings as their design source. The artists would also sketch scenes found in galleries, churches, and palaces as inspiration for their works. A popular image would often be painted by different ceramists on various earthenware pieces, but the source of the design can help identify the narrative’s subject.

For istoriato earthenware, ceramists in the 1800s often referenced narrative etchings as their design source. The artists would also sketch scenes found in galleries, churches, and palaces as inspiration for their works. A popular image would often be painted by different ceramists on various earthenware pieces, but the source of the design can help identify the narrative’s subject.

M&G’s Charger appears to be unique in that the source of the narrative image is unknown, and no other ceramics are known to have a similar subject. Therefore, only details in the image can be used to determine the pictorial scene. The flowing, loose-fitting garments on the three main figures are of the type artists of the time used for Biblical characters. The winged angel pointing a direction and the three putto leading the procession further suggest a Biblical illustration.

For many years, Flight of the Holy Family into Egypt was the title associated with the charger; however Mary, Joseph, and the infant Jesus were the only Biblical characters involved in the secretive escape from Herod’s slaughter of the innocents (Matthew 2:13-21). The missing infant Jesus and the second adult male on M&G’s charger make this assumption unlikely. Also, the angel instructing Joseph to take his family to Egypt appeared to him in a dream prior to the journey and is rarely included in paintings of the subject by the Old Masters. Additionally, the Holy Family was of modest means and traveled discreetly; yet the charger depicts a large entourage of people and animals behind the three mounted figures. Neither does the imagery follow typical illustrations of the family’s return from Egypt.

More likely the scene is Abraham, his wife Sarah, and nephew Lot on their departure to Canaan. God directed Abraham to travel “unto a land that I will shew thee.” A pointing angel and the procession of putto are used as an artistic rendering of God’s directing the travelers. The 75-year-old Abraham, his “fair. . . to look upon” wife, and the younger Lot correspond to the mounted figures on the charger. Their servants, belongings, and herds are depicted following the main figures (Genesis 12).

While a great deal is known about M&G’s charger, many questions remain unanswered. Was this rarely depicted scene part of a set of dishes and serving pieces illustrating various biblical scenes? If so, do other pieces of the set exist? Or was this piece a unique, limited commission for a specific purpose? More research may reveal answers, but some specifics may never be known, which only adds interest to M&G’s mysterious, beautiful Majolica Charger.

William Pinkston, retired educator and M&G volunteer

Published 2021

Suggested References:

Edwin Long is one of several 19th-century English painters who traveled to the middle east. In this work we see colors, textures, and designs derived from these memorable journeys.

In this segment, Bob Jones, Jr. shares the story behind what almost happened to this beautiful Tiffany mosaic.

In this segment Director Erin Jones shares some of the cultural milieu of the Victorian woman.

The Victorian Woman from Museum & Gallery, Inc. on Vimeo.

To view the next video in the series, click here.

In this segment writer Caroline Norton and philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts share reforms they inspired on behalf of Victorian women.

To view the next video in the series, click here.

Florence Nightingale’s understanding of Joseph Lister’s germ theory, along with her tireless work at Scutari during the Crimean War, would bring the nursing profession into the modern era.

To view the next video in the series, click here.