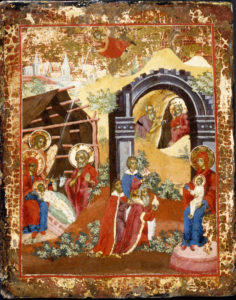

Narratives from the Early Life of Christ

Wool tapestry

Franco-Flemish, c. 1480

In Western church tradition, celebrating the twelve days of Christmas begins December 25 and culminates on January 6 with the Feast of Epiphany on Twelfth Night. According to The Golden Legend by Jacobus de Voragine (Archbishop of Genoa in 1275), this day commemorates four special events in the life of Christ: the adoration of the Magi, and later the baptism of Christ by John the Baptist, the miracle at Cana of the water turned into wine, and the miracle of feeding the five thousand with five loaves and two fish.

Scripture is unclear about the dates of these four events; however, chapter two of Matthew’s Gospel recounts that the wise men from the East came not thirteen days after Christ’s birth, but some two years. The Magi followed the star to Roman-occupied Jerusalem, where they visited King Herod hoping to learn of the promised Messiah’s birth. Unaware and troubled by the news, Herod assembled the chief priests and scribes to discover Christ’s birthplace, which was cited by the prophet Micah as Bethlehem in the land of Judah. Herod directed the noble travelers and requested they return to let him know where the young king was so that he too could worship.

The Magi found and worshipped the Christ child and offered Him three generous gifts, but they were warned in a dream not to return to Herod and departed a different way. Joseph too was advised by an angel to flee to Egypt to protect Jesus from Herod’s murderous jealousy—his massacre of innocent male children two years and younger.

Possibly handcrafted by a guild weaver in Tournai, France in 1480, M&G’s tapestry is roughly 4.5 feet high by 11 feet long. It tells a visual narrative of three scenes following the Magi’s remarkable visit: Herod ordering the murder of the children, the massacre of the innocents, and the family’s flight to Egypt.

Tapestries have a long history dating back to Egyptian and Roman times. However, from the Middle Ages up to the French Revolution, weaving flourished in France and Flanders as an outgrowth of interest from both the church and wealthy nobility. Tapestries were once functional, beautiful, and personal—full of purpose and reflecting the beliefs, skill, economics, and status of the times.

In the 15th century, tapestries often focused on heroes, particularly the Nine Heroes of pagan history (Hector, Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar), Jewish history (Joshua, David and Judas Maccabeus), and Christian history (King Arthur, Charlemagne and Godfrey de Bouillon). However, in this age of chivalry there was a parallel focus on nine heroines including the “greatest lady of them all,” Christ’s mother Mary. M&G’s Narratives from the Early Life of Christ is one of a series of six tapestries depicting the life of the virgin. In 1499 Leon Conseil, who was Chancellor of the Cathedral of Bayeux, cannon of Arry, and secretary of the bishops of Bayeux (Louis de Canossa and vicar general of Cardinal de Prie) gave the tapestry series and a pension for their care to the Cathedral of Bayeux—a church dedicated to Mary and one of France’s greatest and most notable cathedrals.

Phyllis Ackerman in Tapestry, the Mirror of Civilization explains the import and placement of such a gift, “The feudal devotion to a patron was equally practiced by the towns, for each had its patron saint to whom the Cathedral or finest church was usually dedicated, and just as a knight would trace his descent to his hero, so a city often attributed, if not its foundation, at least important moments in its early history to its saint. The lives of these saints were rendered into tapestry to decorate the church, usually on long, horizontal bands to hang around the choir.”

According to the 1901 Normandy Annals, M&G’s tapestry survived the French Revolution and still remained with the Cathedral (hanging in the library) until the city of Bayeux determined to deaccess it. It then passed through multiple collectors including John Pierpont Morgan, Georges Hoentschel, Clarence H. Mackay, and French & Co. before joining M&G’s collection in 1960.

Erin R. Jones, Executive Director

Published 2022