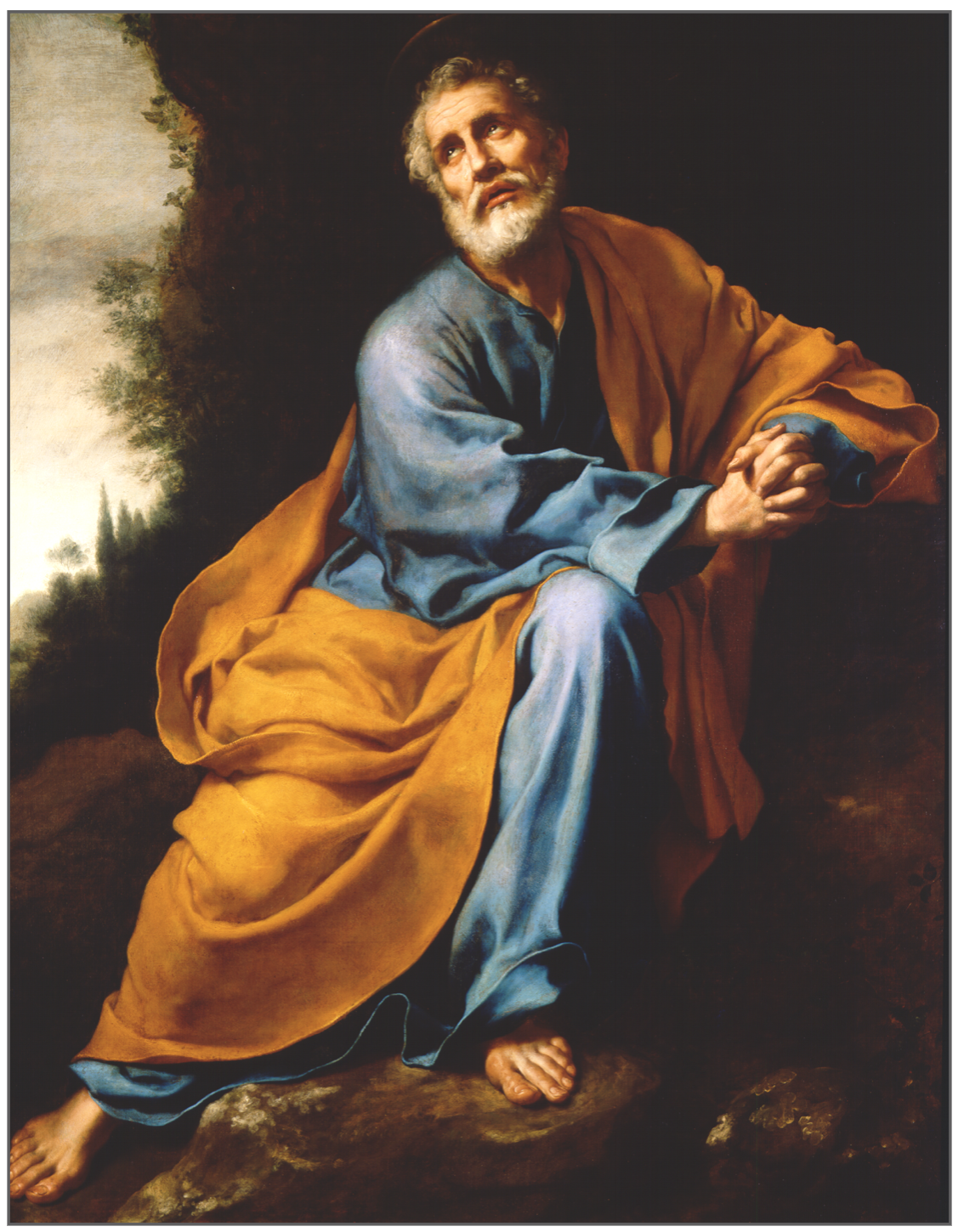

The Mocking of Christ

Oil on canvas

David de Haen

Dutch, c. 1597-1622

And when they had platted a crown of thorns, they put it upon his head, and a reed in his right hand: and they bowed the knee before him and mocked him, saying, Hail, King of the Jews!

Matthew 27:29

Artist David de Haen is the creator of this interesting canvas, which is called a lunette due to its half-moon shape. The painting is a variant copy painted by the artist of the original subject (and same shape) created for the Pietà Chapel in San Pietro de Montorio in Rome. The original lunette was designed to hang above the large altarpiece depicting Christ on The Way to Calvary. The church has multiple small chapels decorated by various prominent Italian painters from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; however, two seventeenth-century Dutch painters are also represented, and de Haen is one of them.

De Haen was born in Amsterdam sometime around 1597 and lived very briefly—just 25 years—with much of his time spent in Rome. Before his death in 1622, he created some notable works including the Entombment, which was destroyed in Berlin during World War II. The commission for the Pieta Chapel was shared with Dirck van Baburen, an artist also represented in M&G’s collection with St. Sebastian Aided by St. Irene. Both de Haen and Baburen were influenced by Caravaggio’s dramatic style. After his time in Rome, Baburen returned home to Utrecht, where he is credited as a key influencer of the Utrecht Caravaggisti—a group of artists following Caravaggio’s well-known trademarks of realistic representations of people and stark contrast of brilliantly lit scenes against darkly shadowed settings.

De Haen was born in Amsterdam sometime around 1597 and lived very briefly—just 25 years—with much of his time spent in Rome. Before his death in 1622, he created some notable works including the Entombment, which was destroyed in Berlin during World War II. The commission for the Pieta Chapel was shared with Dirck van Baburen, an artist also represented in M&G’s collection with St. Sebastian Aided by St. Irene. Both de Haen and Baburen were influenced by Caravaggio’s dramatic style. After his time in Rome, Baburen returned home to Utrecht, where he is credited as a key influencer of the Utrecht Caravaggisti—a group of artists following Caravaggio’s well-known trademarks of realistic representations of people and stark contrast of brilliantly lit scenes against darkly shadowed settings.

Dr. Jones Jr., M&G’s founder, acquired the painting for the Collection in 1986 and explained his fortuitous find, “It came up in an auction at Christie’s, and I noticed in the catalog that, when I measured it and checked the proportions, they exactly fit the end of the room (Gallery 5); so I bought it and put it here, although it is later than the other pictures in th[at] small gallery.”

A closer study of M&G’s painting reveals two men mocking Christ; both are dressed in period clothing of de Haen’s day. Two, less obvious individuals are seen in the background and could possibly represent Pilate and Herod or Caiaphas and his father-in-law Annas. The bench on which Christ is seated may allude to the stone slab that will ultimately entomb Him. The stone’s sculptural relief is similar to carvings found on Roman marble and limestone sarcophagi, which sometimes depicted narratives from the person’s life.

As you enter this Easter season, consider these words written by one of His closest followers, the apostle Peter: “For Christ also hath once suffered for sins, the just for the unjust, that He might bring us to God, being put to death in the flesh, but quickened by the Spirit” (I Peter 3:18).

John Good, Security Manager and Docent

For Further Study:

Podcast about David de Haen by Dutch expert Dr. Wayne E. Franits

About the artist himself

Published in 2020