This work by an unknown 17th-century Italian painter beautifully unfolds the message of unmerited grace offered to mankind by a holy God.

Tag Archives: baroque naturalism

The Triumph of David

Oil on canvas, c. 1630s

Jacopo Vignali

Florentine, 1592-1664

Italian art scholar Howard Hibbard once observed, “Florentine seventeenth-century art has a fascination and beauty worthy of our attention: it is a sensuously colorful and romantic school of painting, sometimes even magical or mystical.” The Museum & Gallery’s Triumph of David by Jacopo Vignali is a case in point. Described as one the most “poetic and sensitive” of the Florentine painters, Vignali began his career at 13 under the tutelage of Matteo Rosselli. In his early twenties he joined several other noteworthy artists in the decoration of the Casa Buonarotti—the most important commission in Florence at that time. By his early thirties, he was not only a member of the Academy but also one of the leading artists in Florence.

Rosselli’s superb tutelage provided Vignali with the technical and artistic skills necessary for his later success. However, as Vignali’s style matured, he became more eclectic, incorporating Counter-Mannerism with the grandeur, drama, and emotional intensity of the emerging Baroque aesthetic. This diversity is clearly apparent in The Triumph of David.

Seventeenth-century paintings on the life of David had been prevalent since the 15th century when the innovative, stunning sculptures of Donatello, Verrocchio, and later Michelangelo elevated this biblical figure into a civic symbol. Interestingly, our M&G painting was originally attributed to Vignali’s teacher Rosselli. Joan Nissman notes: “The answer to this problem of attribution, as Del Bravo suggests, seems to be that it is an early work painted while Vignali was still under the influence of his master. Vignali, in this painting, shares his master’s solid and smooth technique as well as his concern for details of costume.” However, a comparison of Rosselli’s treatment of the subject [fig. 1] with Vignali’s highlights why Carlo del Bravo’s attribution of the work to Vignali (rather than Rosselli) has now won general acceptance.

Notice that in Rosselli’s rendering we see the coloration, composition, and scale indicative of the classical Baroque style popularized by the Carracci. In contrast, Vignali’s more dynamic composition, vivid coloration, and careful use of scale reflect his mature style which favored the integration of Counter-Mannerist techniques with the dramatic realism of Baroque naturalism. For example, High Mannerist paintings were often characterized by strained poses, distortion of the human form, crowded compositions, garish coloration, and unusual (sometimes bizarre) elements of scale.

In this scene, however, Vignali manipulates these common characteristics to create a “restrained” but equally dramatic effect. For example, the composition is “crowded” but the poses elegant, the figures without distortion. The coloration is vivid but not garish, carefully integrated to create focus and highlight the triumphant mood of the scene (e.g., David’s bright red stockings draw the eye to Goliath’s head while the bright red sleeves of the woman’s costume create an implied horizontal line that guides the viewer’s eye back to the hero’s face).

Vignali also carefully manipulates scale. The extreme elongation of the sword and the enormous head of Goliath subtly serve to reinforce the power of the biblical narrative. Scripture notes that Goliath was about 9 feet tall, and although we are not told specifically how much his sword weighed, we do know that the head of his spear weighed about 15 pounds! In addition, the soft modeling of the faces, the contemporary dress, and the morbidly gruesome severed head highlight Baroque naturalism’s penchant not just for realism but also for the “bizarre and strident” (David Steel).

Although Vignali’s contributions to the early Baroque period are significant, he remains less well-known than either his teacher Matteo Rosselli or his most famous student Carlo Dolci. Joan Nissman attributes this lack of name recognition to the fact that, unlike Roselli and Dolci, the great seventeenth-century Florentine biographer, Filippo Baldinucci, did not write of Vignali’s life. Regardless, this work has long been praised as one of the finest treatments of The Triumph of David ever produced.

Donnalynn Hess, Director of Education

Works Cited:

Steel, David, Baroque Paintings from the Bob Jones University Collection. North Carolina Museum of Art.1984.

Hibbard, Howard and Nissman, Joan, Florentine Baroque Art from American Collections. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1969.

Published 2025

Lamentation over the Dead Christ

Oil on panel, c. 1610–12

Abraham Janssens

Flemish, c. 1575–1632

When the word “baroque” is mentioned, there are two names that people associate with this art history movement—Italian artist Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio and Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens. Both artists dominated Europe with their dramatic scenes, rich colors, chiaroscuro, accomplishments, and larger-than-life personalities. In the shadow of these masters and their artistic masterpieces, other artists have done their best to imitate or infuse their own style with these titans’ techniques. One such artist is fellow countryman to Rubens, Abraham Janssens.

Janssens’s work had impressive range. Throughout his career, his subject matter included biblical, historical, and allegorical scenes as well as occasional portraits. His stylistic changes are perhaps the most interesting. The first paintings of his oeuvre would be labeled Flemish Mannerist. Then after a trip to Italy in the early 1600s, he began to adopt a more Caravaggesque approach. Finally, his work became more Rubenesque after Rubens returned home and began to command the Flemish art scene. Janssens’s shift in his different styles can be seen in one specific subject matter—the Lamentation of Christ.

The Lamentation of Christ is an extra-biblical subject that portrayed groups of people mourning around the dead Christ. As mentioned in the gospels (Matthew 27:59-61, Mark 15:46-47, Luke 23:53-56, and John 19:38-42), this group usually included His mother, Mary, and various others. It is the perfect subject matter to compare Janssens’s stylistic shift since it shows strong emotion, sculptural figures, and a dramatic biblical narrative.

First, is Janssens’s Lamentation of Christ painted between 1600 and 1604. This work shows typical Mannerist characteristics with its bright colors and elongated figures. There is emotion, but it is not the intense drama of the Baroque. Since Janssens was in Rome from 1598-1601, it is interesting to note that he did not immediately adopt Caravaggio’s style. According to 17th-century Dutch painting scholar, Justus Müller Hofstede, most of Caravaggio’s early innovations in Italian painting (ca. 1593-1598) such as half-figure compositions, still-life painting, and secularization of religious themes were already in use in Antwerp. Hofstede concludes that Caravaggio’s early pioneer work wouldn’t have impressed Janssens.

It wasn’t until 1607 that Janssens began incorporating Caravaggio’s technique. This style is wonderfully shown in the Museum & Gallery’s Lamentation Over the Dead Christ, painted between 1610-1612. There is a marked stylistic shift to baroque characteristics compared to the first Lamentation. There is a sculptural, monumental quality to his figures, which would become a trademark of Janssen’s career. The lighting is harsh and dramatic and reminiscent of Caravaggio’s best works. This Lamentation also shows an extreme depth of sorrow. The furrowed, anguished brow on Mary is a contrast to the first Lamentation’s rather passive Mary.

Finally, Janssens began adapting to a Rubenesque approach. His later The Lamentation over the Dead Christ painted in 1621-22 includes similar elements from M&G’s Caravaggesque example. However, it does not have the same harshness or extreme sorrow. You can see Rubens’s influence in the rich coloring and more dramatic movement throughout the composition. Janssens still maintains his trademark stiffness and sculptural feel to his figures. According to historian Irene Schaudies, it is Janssens’s focus on his figures looking like classical statues rather than painting from empirical observation like Caravaggio and Rubens that kept Janssens in their shadow. Nevertheless, by looking at these three paintings, one can appreciate what a master Janssens was with his different stylistic portrayals of one of the most emotive scenes in Scripture.

KC Christmas Beach, M&G summer art educator

Published 2025

Luca Giordano, a child prodigy, would become one of the Baroque era’s most noted Neapolitan artist. M&G has at least three of his works including The Triumph of Miriam.

St. Anthony of Padua

Oil on Canvas, 1658

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, called Il Guercino

Cento, 1591–1666

Long before social media, opinions were influential. And, in art history, opinions have affected perspectives toward artists and their work for entire generations. One example of this is the brilliant philosopher of the Victorian era, John Ruskin, who was an art critic that championed JMW Turner, Britain’s greatest landscape painter. Ruskin preferred and praised the contemporary artists of his day such as Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites, the art prior to Raphael, and the Gothic style.

In contrast, Ruskin’s opinion about the Italian Baroque period can essentially be summed up by his reaction to one painting in the Brera Gallery in Milan by Guercino, “partly despicable, partly disgusting, partly ridiculous” (Ruskin, p.203). He classified many of the great seventeenth-century painters within what he labeled “the School of Errors and Vices” (Ruskin, pp.144-45). Such strong views influenced the collecting habits of collectors and museums in Europe and America for several decades. Consequently, Baroque artists are still recovering from the stigma; their names are not as well-known as the Renaissance masters even though their skill is of equal quality.

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, called Il Guercino was one of the most important and talented painters of the Italian Baroque period. He hails from the region of Emilia-Romagna, born in the small town of Cento, which is close in proximity to the artistic centers in Ferrara and Bologna. He was largely self-taught (influenced by works of Ludovico Carracci and Caravaggio), although he studied with local artists Paolo Zagnani and Benedetto Gennari.

Guercino’s nickname means squint-eyed or cross-eyed possibly due to an eye condition, yet this disability didn’t seem to affect his work. Ludovico Carracci praised him in Bologna, and his “genius was recognized by the Bolognese canon Padre Antonio Mirandola, who became his earliest protector and obtained the artist’s first Bolognese commission in 1613” which established his career. “He was then patronized by the papal legate to Ferrara, Cardinal Jacopo Serra,” Duke of Mantua Ferdinando Gonzaga, and the Bolognese cardinal Alessandro Ludovisi, who later become Pope Gregory XV— summoning Guercino to Rome in 1621 (de Grazia, p.157).

Following the pope’s death in 1623, Guercino returned home to Cento to work, painting a wide range of subjects and drawing countless distinctive studies in red chalk and ink. As an artist, he was truly inventive, a real creative. He would put his ideas to paper very quickly and spontaneously—something his biographer Malvasia described as guizzanti, meaning “dart with a flick of a tail, as fishes” (Brooks, p.12).

Among other requests, he was asked to become official painter to the courts of England (1626) and France (1629 and 1639). After the death of his archrival Guido Reni in 1642 he moved his studio to Bologna. By the 1650s, his European patronage had tapered to more local commissions, which is when M&G’s painting was made.

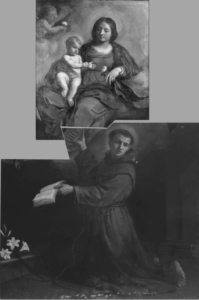

St. Anthony of Padua features the thirteenth-century Doctor of the Church, who was born in Lisbon. He joined the Franciscan Order (represented by the dark brown robe and tonsure haircut) and became a close friend and follower of Francis of Assisi. He had a vast knowledge of scripture and was a gifted preacher, serving in France and Italy including Bologna and Padua, where he died. After his death, he was made the patron saint of Padua.

In art, Anthony is depicted in various scenes describing events from his life. M&G’s subject is the vision of the Virgin and infant Christ—a common theme during the Counter Reformation. The vision came while Anthony was in his room, and he is portrayed with a book (which identifies his learning), lilies (representing his purity), and a crucifix (in the shadows above the lilies).

At the time of acquisition in 1973, M&G’s founder knew that this painting was referenced in the artist’s account books—it was one of two St. Anthony altarpieces recorded. The great Guercino and Baroque specialist, Sir Denis Mahon wrote Dr. Bob, “I have no doubt whatsoever from studying the painting itself that it is an authentic late work by Guercino…. It was the lower half of a picture which had been very much bigger…. It follows that the picture is likely to have originally been a full-size altarpiece” (M&G files).

In the 1990s, Richard Townsend found that of the two St. Anthony altarpieces referenced in Guercino’s account books, one was still in Verona and the other cut in two and sold. This work remained a mystery, until recent years when Italian art historian Enrico Ghetti pieced together the history based on the confusing details in Guercino’s Book of Accounts and Malvasia’s biography. M&G’s painting was once called the Madonna and Child with Saint Anthony of Padua and paid for in 1658 by Pier Luigi Peccana (from Verona) most likely on behalf of the Marquis Gaspare Gherardini. The altarpiece used to hang in the Chapel of Saint Antony at the Capuchin church of Verona.

Ghetti suggested the painting, Madonna with Child, which was formerly in the Sgarbi collection in Italy is most likely the upper portion of our work; he has proposed a reconstruction of the dismembered altarpiece as seen here.

M&G’s painting reveals some of the standard matters art historians encounter regularly: the influence of art critics like John Ruskin, the connoisseurship of art specialists like Sir Denis Mahon, dismembered altarpieces, and confusing primary records for art scholars like Enrico Ghetti to ferret out. More importantly, this interesting work represents one of the most notable and innovative Italian painters of the seventeenth century.

Erin R. Jones, Executive Director

Bibliography

Brooks, Julian. “Characterizing Guercino’s Draftsmanship.” Guercino: Mind to Paper. Getty Publications: Los Angeles, 2006.

De Grazia, Diane. “Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, Called Il Guercino.” Italian Paintings of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries: The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue. National Gallery of Art, Washington: New York, 1996.

Ghetti, Enrico. 2020. “La ricostruzione di una pala del Guercino: la Madonna col Bambino e sant’Antonio d Padova per i Cappuccini di Verona,” Storia dell’ Arte 153, Nuova Serie 1.

Ruskin, John. Modern Painters (vol. ii), ed. Edward T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn. George Allen: London, 1903.

Ruskin, John. Ruskin in Italy: Letters to His Parents, 1845, ed Harold I. Shapiro. Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1972.

Published 2025

The Return from the Flight into Egypt

Oil on canvas, c. 1712

Giuseppe Bartolomeo Chiari

Roman, 1654-1727

Rome was for centuries the epicenter of culture, art, and religion. At the time of Giuseppe Chiari’s birth, it was also “the scene of a lively debate with a constantly varying interplay of influences, trends, fashions, specialized treatises, and, of course, great masterpieces” (Zuffi, p. 64). At the center of this debate were three artistic movements that Zuffi notes “succeeded one another in a sort of ideal relay race of artistic styles.” The stark naturalism of Caravaggio, the elegant classicism of Annibale Carracci, and the dramatic baroque sculptures and architecture of Gian Lorenzo Bernini would all play a part in making 17th-century Rome—well, Rome!

As president of the Roman Academy Carlo Maratta was keenly aware of these lively debates. Considered one of the most important painters in the latter half of the 17th century, he was much admired for his beautiful frescos and stunning portraits. Although his work evidenced a clear admiration for the classical tradition, several of his paintings also integrated elements of Caravaggio’s vigorous style. David Steel points out that Maratta often “managed to steer a middle course between these two dominant and often contrary trends of baroque painting” (Steel, p. 88).

Maratta was at the summit of his career in 1666 when 12-year-old Giuseppe Chiari entered the great master’s studio. Chiari soon became a star pupil. Over the years, his profound respect for Maratta’s tutelage would not only shape his artistic development but also ensure his future success in a highly competitive environment. When Maratta died in 1713, Chiari took up Maratta’s mantle and became the dominant Roman artist.

Like Maratta, Chiari broadened his appeal by becoming an astute observer and deft practitioner of integrating stylistic trends. Kathrine and William Wallace highlight this skill in their comparative analysis of Chiari’s Tedallini altarpiece with Caravaggio’s Madonna dei Pellegrini [figs. 1 and 2]:

“The statuesque pose of Chiari’s Madonna, the unusually high step on which she stands, the elongated form of the Christ child framed by a white swaddling cloth, and the overall right-triangular composition recall Caravaggio’s Madonna dei Pellegrini. Yet the suggestion is subtle: Chiari has reversed the composition, naturalized the pose of the Virgin, and substituted the more palatable, well-dressed saints for the dirty feet and common character of Caravaggio’s pilgrims. Although inspired by Caravaggio, Chiari’s altarpiece remains distinctly his own. Chiari’s Madonna looks like a person of warm flesh and blood rather than the marmoreal statue of Caravaggio’s Madonna; Christ is an attractive child of sweet disposition as opposed to the enormous and ungainly figure depicted by the older master. Instead of the muted and earthy colors of the Madonna dei Pellegrini, Chiari’s bright hues are immediately pleasing and a welcome contrast to the comparatively dark paintings found on so many Roman altars” (p. 4).

The Return from the Flight into Egypt provides another example of Chiari’s virtuosity and unique style. Here, however, he turns from echoing the past to adumbrating the future. The refined handling of the paint and elegant figural poses pay homage to the classical tradition; however, the playfulness, delicate coloration, and ornamental enrichment mark the transition into the sensuous, intimate style of the rococo movement which emerged in France and spread throughout Europe in the 18th century (Chilvers, 507).

M&G has two works by Chiari on this subject, one titled The Rest on the Flight into Egypt and this rendering titled The Return from the Flight into Egypt. Over the years scholars have found the less traditional title of this 1712 work problematic. However, “the light-hearted, almost celebratory mood” (echoed in the Rococo style) reinforce the idea that here, Chiari intends to highlight the family’s return from rather than flight into Egypt. Regardless of the debate, art experts like Christopher Johns note that this picture may be the best example of Chiari’s work in America.

Donnalynn Hess, M&G Director of Education

Resources:

Baroque Paintings from the Bob Jones University Collection by David H. Steel

Concise Dictionary of Art and Artists, 3rd edition by Ian Chilvers

“Giuseppe Bartolomeo Chiari,” The Art Bulletin, March, 1968, Vol. 50, No. 1 by Bernhard Kerber and Franciscono Renate

“Seeing Chiari Clearly,” Artibus Et Historiae, 2012, Vol. 33, No. 66 by Katherine M. Wallace and William Wallace

Published 2024

Although little is known about the Italian artist Pietro Martire Neri, this portrait illustrates his stunning mastery of beautiful coloration and intricate stylistic detail.

Monthly Update

Sign up here to receive M&G’s monthly update and collection news!

EXPLORE More Online Features

Speakers Bureau

We can speak for your retirement group, civic club, church fellowship, or book club. Contact us here or at 864-770-1331.

Support Our Work

Make a Gift to M&G to help our current work and future plans.