Oval Dish: The Baptism of Christ

Earthenware with lead glaze

Bernard Palissy (follower of)

French, 16th or 17th century

Click on the links throughout the article to further your learning.

The Artist

Bernard Palissy (1510-1590) has been called “the Leonardo Da Vinci of France.” Both artists came from poor, country roots and became famous for their artistic and scientific achievements. Palissy wrote about the causes of natural phenomena like springs, earthquakes, and the crystallization of salt. He proposed agricultural methods and designs for gardens and cities. Many of his conclusions were correct, and his writings were studied for scientific insights hundreds of years after his death.

Like Da Vinci, Palissy is most famous for his artistic accomplishments, particularly for what he called rustiques figulines (today called rustic ware or Palissy ware). Snakes, frogs, crayfish, fish, insects, ferns, flowers, leaves, shells, rocks, and other natural items were cast in plaster or similar materials and then used as molds for the clay figures that would be artfully affixed to basins, platters, pitchers, and vases.

Da Vinci experimented with various media as he created masterpieces, and not all his explorations were successful. To achieve certain effects, Palissy tested clay from different sources in a single piece. Since clays respond differently when fired, there were many failures. Various glazes also require different temperatures to bond properly to clay. During one of his experiments Palissy needed more fuel to reach the proper temperature. He used his wooden furniture and the flooring of his house to feed his kiln.

Da Vinci was christened a Catholic, and his religious paintings reflect traditional catholic iconography, although often with a humanistic twist that reflected his worldview. Palissy was also christened a Catholic, but sometime in the 1550s became a Huguenot. This Protestant group adhered to Calvinistic doctrine (John Calvin and Palissy were contemporary Frenchmen, but it is doubtful they ever met). Palissy helped found the first Huguenot church in the city of Saintes and occasionally served as its lay preacher. The Catholic government sought to remove the Protestant heresy through trials, imprisonment, torture, and wars. Being a well-known Protestant, Palissy was repeatedly arrested, tried, and imprisoned for his beliefs.

Just as Da Vinci had powerful, wealthy patrons, so did Palissy. One of the most powerful men in France, Anne de Montmorency amassed an impressive art collection, including a Michelangelo. Several Palissy rustic ware pieces were in his collection, and he used his influence to have Palissy appointed Inventor of Rustic Ware to the King, which aided in his being released from imprisonment. De Montmorency commissioned Palissy to build a grotto—a garden building with an interior designed to appear like a “natural” cave—for his chateau. Grottoes usually included mythological or symbolic figures, often with a fountain centerpiece. They developed into a key expression of wealth, artistic taste, and political views.

In 1562, Palissy was charged with destroying “sacred church images” during a Protestant riot. He denied the charge in court but was imprisoned and his studio ransacked. Cunningly, Palissy wrote to his patron but did not deny the charges nor plead for release. Instead, he described the grotto and how de Montmorency was being defamed by those who destroyed its expensive pieces kept in his studio, which had been “admired by thousands.” Palissy published the letter after which he was soon released.

When de Montmorency died, the unfinished grotto project was abandoned. Meanwhile Catherine de’ Medici (daughter of Lorenzo, wife of the French King Henry II, and later regent for her 10-year old son) was building the Tuileries Palace as her Paris residence. Since Palissy was no longer employed by de Montmorency, she commissioned him to build a grotto for the Tuileries Palace. Palissy brought pieces and molds originally designed for de Montmorency’s grotto to a space set aside for his workshop in the Tuileries gardens.

Little is known of Palissy’s plans for the queen’s grotto; however, the design would be on a grand scale, with the most fashionable artistic illusions. When a visitor looked into the basin of the fountain, for example, he would see the backs of ceramic fish. Ceramic frogs and other creatures spitting water into the basin would create ripples, causing the fish to appear as if they were swimming.

At the end of Da Vinci’s life, he summoned a priest to hear his last confession and was buried in ground consecrated by the Catholic church. As Palissy was approaching 80, he was again condemned for heresy. He spent his last months in the Bastille, where he was poorly treated. Although a friend had secured his release, Palissy knew nothing of it before he died. There is no known grave, although several Palissy monuments have been erected in France.

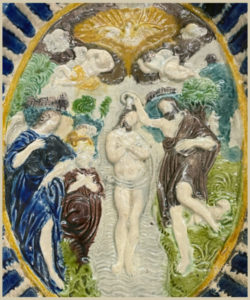

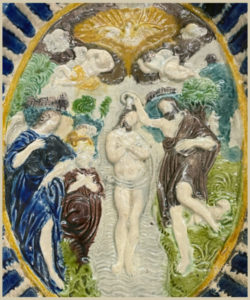

M&G’s Oval Dish

M&G’s ceramic dish of The Baptism of Christ is a 10 ¼ inches by 8 ¼ inches oval. The face and its lip are bas-relief with colored glazes. The design on the blue and white lip represents palm trees, and the dish is mounted on a concave pedestal. The reverse of the dish and the base are mottled blue and maroon glazes.

In the center of the scene, Jesus appears to stand on the water of the Jordan River while John the Baptist (clothed in brown) pours water onto Christ’s head. There is no mention in Scripture of an angelic presence (as pictured in the sky and two on left); although Matthew 3 does reveal that when Jesus was baptized the Spirit of God descended from heaven in the form of a dove and a voice proclaimed, “This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased.” Attending Jesus’ baptism were Pharisees and Sadducees, who had questioned John about his baptizing. These are omitted by the sculptor; however, the kneeling character on the left may be either John the beloved disciple or Mary the mother of Christ.

In the center of the scene, Jesus appears to stand on the water of the Jordan River while John the Baptist (clothed in brown) pours water onto Christ’s head. There is no mention in Scripture of an angelic presence (as pictured in the sky and two on left); although Matthew 3 does reveal that when Jesus was baptized the Spirit of God descended from heaven in the form of a dove and a voice proclaimed, “This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased.” Attending Jesus’ baptism were Pharisees and Sadducees, who had questioned John about his baptizing. These are omitted by the sculptor; however, the kneeling character on the left may be either John the beloved disciple or Mary the mother of Christ.

Later, as John the Baptist describes the event to Jewish rulers, he tells of the dove and the voice which assured him that he had indeed baptized the Messiah. Then seeing Jesus, John proclaims, “Behold the Lamb of God which takes away the sin of the world” (John 1:19-39). Within the dish’s picture, this pronouncement is symbolized by the lamb reclining at John’s feet.

Other Dishes

Early ceramists often copied their images from prints or other works of art, which can help to establish a date for a piece. A source to parallel the image on the Baptism of Christ dish is unknown. The image may be a compilation from several sources. Besides the Baptism of Christ, Palissy and his followers created various allegoric or historic scenes. Two other biblical scenes were frequently repeated: Abraham’s Sacrifice of Isaac and the Beheading of John the Baptist.

Dishes similar to M&G’s are in the Louvre, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the National Gallery in Washington DC, the Cleveland Museum of Art, French National Gallery of Ceramics and other collections. In the past many of these were attributed to Bernard Palissy, but their documented provenance rarely extends prior to the 19th century. Today most are attributed to “a follower of Palissy” or an anonymous 16th or 17th- century ceramist.

It is simple to make a mold of such a piece and produce copies of it. This would have been common practice for popular objects, certainly for Palissy’s lifetime, but also for centuries following. Craftsmen created “stock” objects of art, many devotional pieces, to sell at fairs and in shops—repeating copies from one mold. Over time, copies are made, details become lost, “touch ups” are needed, and glazes (as well as the skill of the glazer) differ.

Palissy did not mark or sign his works. Following his death, contemporary ceramicists, including family members and his studio, continued produced his rustic ware, which was considered inferior. Palissy had not revealed his methods of achieving his ceramic’s characteristic lifelikeness, and his name and work drifted into obscurity until the early 1800s, when a Palissy following emerged, and demand for rustic ware increased. Ceramists of the period discovered how to produce rustic ware that matched Palissy’s quality. Although many signed their work, some passed off pieces as Palissy originals.

The area of Palissy’s Tuileries workshop was excavated in the 1800s and again in the 1900s. Molds and fragments of grotto pieces were found, including the popular spitting frog. Recent scientific analysis of the clay and glazes of these excavated pieces has been compared to works attributed to Palissy. The authenticity of some rustic ware has been reevaluated because they contain materials not available to Palissy.

During excavation in the Tuileries, a fragment of a plaque was found. It bears a similar image of the Baptism of Christ found on M&G’s Oval Dish and on similar dishes in the Louvre, The Victoria and Albert Museum, and other collections. These dishes are probably copies and more likely copies of copies.

M&G’s Oval Dish entered the collection in the mid-1900s. It is difficult to know its creator, but the design certainly reflects the style and techniques of the great innovator Bernard Palissy.

William Pinkston, retired educator and M&G volunteer

Bibliography

Leonard N. Amico, Bernard Palissy – In Search of Earthly Paradise

Christian Study Library

Patricia F. Ferguson, Pots, Prints and Politics: Ceramics with an Agenda, from the 14th to the 20th Century

Marshall P. Katz and Robert Lehr, Palissy Ware – Nineteenth-Century French Ceramists from Avisseau to Renoleau

Marielle Pic, “Un céramiste de légende : Palissy à Sèvres”

Hanna Rose Shell, “Casting Life, Recasting Experience: Bernard Palissy’s Occupation between Maker and Nature”

Published 2022