Esau and Jacob Presented to Isaac

Benjamin West, P.R.A.

Below the image, click play to listen.

You can learn more about the entire series by West and M&G’s significant collection from the series HERE.

Benjamin West, P.R.A.

Below the image, click play to listen.

You can learn more about the entire series by West and M&G’s significant collection from the series HERE.

Walnut

This William and Mary Cabinet on Stand came into the Museum & Gallery’s collection in 1970, through the generosity of a prominent Asheville physician, musician, author, and collector of art and antiques, Dr. Charles S. Norburn. Dr. Norburn served as a Navy surgeon in World War I, then in Navy hospitals in Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. He was even appointed by the U.S. Surgeon General to serve as personal surgeon to President Warren Harding on a trip to Alaska. After leaving the Navy, Norburn returned to North Carolina in 1923 and established the cutting-edge Norburn Hospital Clinic in 1928. The Norburn Hospital’s second building, with 32 acres of property, stood on what is now part of the Mission Health campus, leaving a lasting legacy of care in Western North Carolina. His donation to M&G has left a lasting cultural legacy in the western Carolinas, as well.

Much from the period of William and Mary (1689-1702), including the furniture characteristic of that era, reflects the religious atmosphere of the day. While it would oversimplify the case to say that religion was the sole explanation for the furniture fashion of the day, most sources do note the significant influence religion had upon it. Indeed, there would not have been a “William and Mary” period, had it not been for the “Glorious Revolution” of 1688, which deposed James II from the English throne and made him notable for being the last Roman Catholic monarch of England.

James II had succeeded his elder brother, Charles II in 1685, when Charles died without a legitimate heir. Early in his reign, Charles II had urged his younger brother to rear his daughters as Protestants, despite the fact that James and his wife were Catholic. Thus, when Charles II died, the throne passed to James II and established his elder daughter, Mary (b. 1662), as heir apparent. Mary had married her cousin, William of Orange, in 1677, when she was just 15, and moved to the Protestant Netherlands with her husband.

From the start, James II’s overt Catholicism alienated the majority in England. That dissatisfaction was amplified in 1688 with two crises—the birth of a son to James, (raising fears of a Roman Catholic dynasty), and very public conflicts with the king over religious tolerance.

Seven highly placed Englishmen (an Anglican bishop and six prominent politicians) wrote to William of Orange, inviting him to come set right the country’s grievances. William sailed to England in November of 1688 with a force of 20,000 men, making his way to London with very little opposition. James II fled to France in December of that year, and Parliament—now cemented as the ruling body in England—pronounced William III and Mary II joint rulers in April 1689.

The “William and Mary style” developed within this religious and cultural milieu. With them, William and Mary brought Dutch craftsmen to England, popularizing a style that had first been seen under Charles II (1660-1685) throughout England and its colonies. The finely inlaid cabinet style of this era had originated in France, but some of the most influential craftsmen were Huguenots. These weavers, painters, joiners and carvers fled to England from France in order to escape the religious persecution that arose after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685). Their influence resulted in a more staid style than the flamboyance of Louis XIV’s court, while still exhibiting the highest craftsmanship and newest fabrication techniques.

The Museum & Gallery’s Cabinet on Stand evidences the traits distinctive to fine cabinetmaking in the William and Mary style. In place of the heavy, horizontal lines of domestic furniture, there was an emphasis on verticality, lifting cabinets on multiple, finely turned or barley-twisted legs. Indeed, the “high boy” and other specialized forms of domestic furniture owe their inception to William and Mary design.

Overall, there was a movement away from the excessive grandeur of the French court and the English Restoration period, but there was also intricacy and high design. Thin slices of highly figured woods (sometimes acacia, olive, or other exotic woods made possible by new East-West trade routes), ivory, and metal were affixed to flat surfaces like cabinet doors and sides, creating contrasting colors for geometric shapes, flowers, birds, and numerous other natural themes. Beneath these veneers, walnut superseded oak as the most frequently used wood species. Atop the veneers, surface treatments like lacquer and other fine polishes became vital to protect and highlight the designs.

In keeping with the above-mentioned traits of William and Mary cabinetmaking, M&G’s Cabinet on Stand features detailed walnut burl veneers and geometric maple inlay on three sides, over a yellow pine substrate. An overhanging cornice rests at the very top, with two drawers and two flush, side-hinged doors beneath. This top portion (the “cabinet” in the designation “cabinet-on-stand”) sits on a base containing two additional drawers and four sophisticated, tapering barley-twist front legs and three simpler turned rear legs. The barley-twist legs taper from being thinner at top and bottom to thick in the middle and demonstrate the cabinetmaker’s skill. A flat display platform sits at the very bottom, raised from the floor on turned bun feet.

Our cabinet is likely from the late 17th century or early 18th century (perhaps 1700-1725) and illustrates the departure from the continental style toward a more staid English and/or Protestant sensibility. It is a presentation cabinet that served for storage in some prominent place of a household, possibly holding linens in the 17th-century equivalent of a dining room. The top and base are flat for display and may have held Dutch majolica, other pottery, or even items from the Orient over the years, depending on the wealth of the owner. This Cabinet on Stand is an important piece in the M&G collection for the history and artistry it brings to life.

Our cabinet is likely from the late 17th century or early 18th century (perhaps 1700-1725) and illustrates the departure from the continental style toward a more staid English and/or Protestant sensibility. It is a presentation cabinet that served for storage in some prominent place of a household, possibly holding linens in the 17th-century equivalent of a dining room. The top and base are flat for display and may have held Dutch majolica, other pottery, or even items from the Orient over the years, depending on the wealth of the owner. This Cabinet on Stand is an important piece in the M&G collection for the history and artistry it brings to life.

Dr. Stephen B. Jones, volunteer

Sources:

David L’eglise, Village Antiques at Biltmore, Asheville, NC

Joseph Aronson, The Encyclopedia of Furniture

Judith Miller, Furniture

Judith Miller, Miller’s Antiques Encyclopedia

Encyclopaedia Britannica

Tim Forrest, The Bulfinch Anatomy of Antique Furniture

Kay West, “Daughter publishes book by pioneering physician father decades after his death”

ceramic

French, 1824 – 1887

English, c 1859

It has been said that the Industrial Revolution robbed the common people of beauty. Leaving the verdant countryside, they moved to cramped cities, worked in dingy factories, and lived in bare housing. Prince Albert, the progressive-thinking consort of Britain’s Queen Victoria, desired a change for his hard-working countrymen. But the beautiful, unique pieces that surrounded aristocrats were expensive. Could not everyday, practical items be beautiful? Could they be mass produced inexpensively? Since one must have a teapot, could it be functional, affordable, and beautiful?

Although Prince Albert addressed the lack of beauty on several fronts, he saw ceramics as part of the answer. At the Great Exposition of London (1851), primarily organized by Prince Albert, a “Ceramics Court” displayed large and small, elaborately decorated, English-made pieces. Exhibits from many countries also featured their unique ceramics. At booths and shops near the Crystal Palace everything from embellished ceramic teapots to ornate chamber pots could be purchased for “reasonable prices.”

Lending royal clout to the Victorian ceramic boom, Prince Albert purchased ceramic brackets matching those in M&G’s collection. They were passed down in the family and today belong to Queen Elizabeth.

From humble beginnings in Stoke-upon-Trent (1793), the Minton Company developed procedures and glazes that permitted them to became one of Europe’s leading ceramicists of the Victorian era. What was originally called Palissy-ware and later Victorian majolica won top prizes for “beauty and originality of design” at the Great Exposition and later international exhibitions as well. The company produced decorative tiles and sculpture for major buildings, including the Palace of Westminster and the US Capitol.

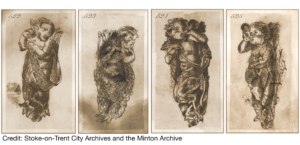

In time the Minton Company dwindled and eventually merged with other firms. The Minton Archive, which contains drawings of the pieces the company produced, remains intact. The records reveal that shape 524 is a pen and ink drawing of M&G’s Faun bracket, labeled “Bracket—Hunting.” Shape 522 is M&G’s Nix (or merbaby) bracket, labeled “Bracket—Fishing.”

The Archive has a pair of Hunting brackets (525 labeled “Companion Bracket—Hunting”) and a pair of Fishing brackets (523 “Companion Bracket—Fishing”). Both Hunting bracket fauns appear to be male. However, different hair lengths indicate Fishing 522 merbaby is male, and 523 is female.

Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse was a prolific 19th-century French sculptor. At age 13 he apprenticed to a goldsmith and learned precision and honed his technique. This enabled him to produce pieces with unusual forms and detail that were able to be mass-produced. He produced monumental statues, portrait busts and a wide array of decorative objects. His works vary from stark realism to ornate neo-Baroque and frequently combine several artistic styles.

In the mid-1800s political turmoil caused a number of artists to leave France. Carrier-Belleuse went to England in 1850 and became “modeling master” at two art schools. He was also employed as a sculptor by the Minton Company. During his 5-year English sojourn he sculpted for other ceramic firms, including Minton’s competitor, Wedgewood. Returning to France his reputation grew, and he was appointed to prestigious positions in the art world.

Astute in business, Carrier-Belleuse maintained a large studio producing copies and variations of his works. He passed on his artistic techniques and business practices to his students, including Rodin, Dalou and Falguière. He also sold reproduction rights for various of his designs to other manufacturers. The Minton Company appears to have had exclusive reproduction rights for his Hunting and Fishing brackets.

In the mid-1800s chubby infants were in vogue and are in a number of Carrier-Belleuse works. It was, however, unusual to combine infants with non-human features, as seen in the Hunting and Fishing brackets.

M&G’s Hunting bracket is a 19-inch faun, blowing a hunting horn over his left shoulder. On the infant’s waist is a draped, grey animal skin, which also forms the background for his lower body. Over his right shoulder he holds the feet of a fox. The head and front legs of the fox are draped around his neck to the faun’s left side. Below the knee the faun has crossed goat legs, typical of this mythological creature. In his hair and behind his head are oak leaves and acorns. Stamped into the reverse is “MINTON” and shape number “524.”

M&G’s Fishing bracket is a 19-inch, male merbaby. He holds a brown fishing net over his right shoulder. It is then wrapped around him. Below the knee each leg becomes an elongated, twisted fish tail. Behind his head and in his hair are cattails.

M&G’s Fishing bracket is a 19-inch, male merbaby. He holds a brown fishing net over his right shoulder. It is then wrapped around him. Below the knee each leg becomes an elongated, twisted fish tail. Behind his head and in his hair are cattails.

Most Hunter and Fisher brackets are glazed in the same colors as M&G’s. The Minton Company also produced them in Parian ware, a biscuit porcelain, designed to imitate marble. Parian brackets have more sculptural details than the colored ones.

Because of their similar size and subject matter, all four wall brackets could be used in a single decorating scheme. Several sets of only the Hunting pair or the Fishing pair are in private collections. The most famous are the pair of Fishing brackets Prince Albert gave Queen Victoria in 1858 for her 39th birthday. Wooden shelves and an angled backing were attached to mount in the corners of the bay window of her bedroom in Osborn. Located on the Isle of Wight, Osborn was the family’s get-away, a beachfront home. Merbabies seem appropriate adornment for windows featuring an ocean view. The bracket shelves still hold busts of Victoria and Albert.

M&G’s brackets are a mixed set: one Hunting and one Fishing bracket. Mixed sets were probably part of their original plan and date back to their manufacture. When Prince Albert redesigned the Royal Dairy on the Windsor Estate, he commissioned ceramic tiles, statues and other decorative and functional ceramic features. However, still hanging on one wall in the Dairy are a mixed pair of Hunting and Fishing brackets (without a shelf), which he did not commission. Interestingly, the Royal Dairy brackets are the exact opposite of M&G’s brackets.

During the Victorian era, substantial amounts of ceramics were produced. Many were nicely styled and decorated, functional pieces. But there were also more elaborate ones with restricted functionality, like M&G’s brackets. Rather than being a unique and thus expensive piece, multiples were manufactured, lowering the price of owning their beauty. Prince Albert would probably be pleased to know that many of these ceramics are still being appreciated today.

William Pinkston, retired educator and M&G volunteer

Bibliography

Albert-Ernst Carrier-Belleuse, Philippe Meunier & Jean Defrocourt

Majolica Mania: Transatlantic Pottery in England and the United States, 1850–1915 by Paul Atterbury

The Life and Work of Albert Carrier-Belleuse by June Ellen Hargrove

Victoria & Albert – Art and Love, Royal Collection Enterprises Ltd

Published 2022

This tender, graceful work by Benjamin West is one of a special series of paintings commissioned by King George III to decorate a chapel at Windsor Castle.

Visit HERE for the next video to think on things that are Worthy of Praise.

Victorian artist, Eyre Crowe does a masterful job of recreating that moment in the town of Wittenberg, Germany that set in motion the Protestant Reformation.

Benjamin West, P.R.A.

Below the image, click play to listen.

You can learn more about the entire series by West and M&G’s significant collection from the series HERE.

Oil on canvas

English, 1829-1891

Vashti showcases Edwin Long’s interest in archeological discovery, religious history, and female beauty on a grand scale, interests that reflect those of the Victorian era in which he lived. And the story of the two queens of Xerxes, king of Persia, is tailor made for both his interests and his skills. Like other religious painters of the era, such as William Holman Hunt, Long actually visited the Holy Land to gain firsthand knowledge. He combined this trip with various print sources such as volume III of George Rawlinson’s The Five Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World (1862-67) and Austen Henry Layard’s studies from Nineveh in order to create this painting of convincing Orientalism. Originally exhibited at Burlington House in 1879 with its companion piece, Queen Esther, the two paintings taken together (though not exhibited side by side) offer food for thought both on the characters of these impressive women and the critical period in which they lived.

Vashti opens the story of Esther with a dramatic refusal to appear at her husband’s banquet for the rulers of the Persian kingdom. Whether she refuses out of modesty (her crossed arms seem to support this position) or because she herself is hosting a banquet for the wives of the rulers, her refusal is seen as a harbinger of marital unrest in the kingdom if her disobedience goes unanswered. So the king is persuaded to depose her as queen and seek a new one. There are several indications that Vashti recognizes the serious implications of her rebellion. She is remonstrated by her maidens, there is an apparent altercation at the door between those delivering her refusal and those demanding her acquiescence, and her body language suggests that she is afraid of what is to come.

The symbolism so greatly loved by the Victorians comes into play through the great lion on which she sits. An emblem associated by the Persians with their great power, the lion reflects both the power that has made her queen and the power which she will be unable to thwart. Though the lion is itself slain and has lost its power over her, even serving as a bench cushion; one lone woman cannot stand against an Eastern potentate. Her name which means “Beautiful One” in Persian appropriately reflects her physical beauty, likely the avenue to her queenly position. However, beauty is hardly a weapon against the mighty Persians. Or is it?

Consider the story of Hadassah or Esther as most know her today. An entire book of the Bible, one in which there is no direct mention of Jehovah, chronicles a few brief years of a young Jewish maiden who had “come to the kingdom” (Esther 4:14) at a crucial time, not just as a result of the whim of the queen. Long means for viewers to examine these women in light of each other. A cursory glance reveals that the two paintings are meant as companions: the matching frames, the seated central figures, the inquisitive gaze and pose of the servant girl, the visible sandaled foot of both women. Even the “X” created by the arms of Vashti and the jewelry of Esther juxtapose these two women and their plights: one is apparently guarding her beauty from the ravaging eyes of the rulers, the other finds her beautiful figure emphasized in the king’s competition.

Consider the story of Hadassah or Esther as most know her today. An entire book of the Bible, one in which there is no direct mention of Jehovah, chronicles a few brief years of a young Jewish maiden who had “come to the kingdom” (Esther 4:14) at a crucial time, not just as a result of the whim of the queen. Long means for viewers to examine these women in light of each other. A cursory glance reveals that the two paintings are meant as companions: the matching frames, the seated central figures, the inquisitive gaze and pose of the servant girl, the visible sandaled foot of both women. Even the “X” created by the arms of Vashti and the jewelry of Esther juxtapose these two women and their plights: one is apparently guarding her beauty from the ravaging eyes of the rulers, the other finds her beautiful figure emphasized in the king’s competition.

Both women are “caught” by their positions though their gazes differ: Vashti’s gaze foreshadows her fall from favor while the frank gaze of the powerless girl (even her beauty is no match for an unextended scepter) foreshadows her strength of spirit. The adorned Esther has put down the mirror, rejecting the offer of more jewels. Instead, just prior to being veiled and taken to Xerxes, she looks directly at the viewer. This gaze, though solemn, reveals no fear in the innocent young girl (notice the lilies on the wall relief behind her) who by the next day will be either a mere concubine or the queen. The mythical griffins embroidered on the hem of her gown were figures used to guard the gold of the Persians and are another indication both of the marketplace contest she is part of and her inability to escape. Yet Esther has an inner strength that enables her to risk death at the hands of the king—in order to invite him to dinner!

Though Vashti is gone by the end of the first chapter of Esther, she begins the rising action of the story whose crisis is faced by her youthful successor. Without the brave action of Vashti, Esther would not have been in place to rescue her people. And without the brave action—and clever thinking—of Queen Esther, the Israelites would have lost their stand against the “divine” power (note the stylized sun on the end of the mirror handle and on Vashti’s belt) of the pagan Persians at the hands of Haman. If “the king’s heart is in the hand of the Lord” (Proverbs 21:1), it is certain the hearts of queens are as well. Edwin Long’s works draw attention to both the historical tensions in the Persian royal court and the metanarrative of the Israelites’ position as God’s chosen people.

Dr. Karen Rowe, M&G Board Member

Published in 2019