The extraordinary life-like quality of the characters in this work illustrate why Francois de Troy was one of the 17th century’s most popular portrait painters.

Tag Archives: French art

The Fountain of Life

Potmetal and stained glass

Unknown

French, 16th century

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Walter W. Lee

Every collection object has a life story to tell, and the fascinating narrative of these beautiful windows begins in the fertile flood plain of the Loire Valley in France, near Saumur…

The Windows’ Story

At his mother’s passing, Baron René de Thory inherited estate and lands as the new Lord of Boumois. His wealth included the ruins of a castle once owned by the Counts of Anjou and which was destroyed during the Hundred Years War. Following his marriage to Françoise du Plessis, René undertook the building of Chateau Boumois between 1521 and 1525 on the remains of the former Angevine castle.

The chateau’s designs included private living quarters, guest areas, public entertaining areas, kitchen, bakehouse, pantry, cellar, and towers. As is fitting the role of the Lord of Boumois who held a seat of authority, the house included a dungeon and space for hearing judicial cases. To run such a household required servants, their living quarters, stables, a courtyard, and a dovecote. Since the area was a central hub for the activity of those living and working on the estate, there was a chapel for worship; and all at the castle were protected by a surrounding moat.

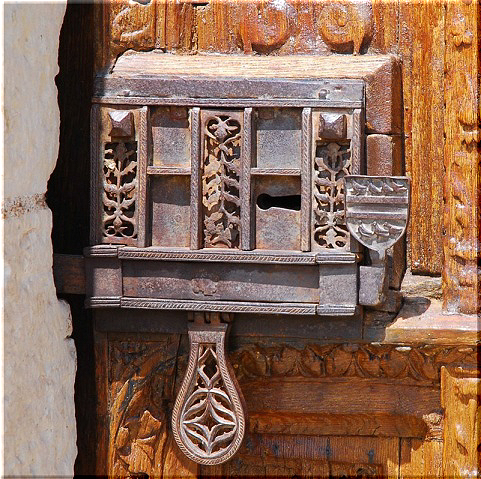

In Anjou, there are some 1200 castles remaining today; Boumois is classified as a French Historical Monument and is one of the last remaining castles of Gothic architecture. Christian Cussonneau writes, “Boumois still offers today despite some mutilations, the essential features of a manor house at the end of the Middle Ages.” On a beautiful imposing, carved door at the chateau, there still remains the de Tory coat of arms on the lock (see image).

The chateau’s chapel was completed by 1525. To appropriately beautify the space, René de Thory commissioned stained glass windows, which were most likely created and installed before his wife, Françoise du Plessis, passed away in 1528/9. The chapel windows consisted of three sections:

- The central window of three panels: the Fountain of Life

- On the West wall: two lancets featuring the donor, René de Thory, presented by St. René to the Virgin of Pity (also known as the Pieta). De Thory is depicted as a kneeling knight wearing his family coat of arms; the window includes the Latin inscription: Omniae dei memoria mei meaning “Remembering that all things are for God.”

- On the East wall: two lancets featuring Françoise du Plessis presented by St. Francis of Assisi to the Virgin and Child with saints (most likely including St. Barbara, the patroness of the daughter of Lord and Lady Boumois). These panels have since disappeared and are known only from written sources from the nineteenth century and supposedly by a photograph taken around 1890.

Not long after his wife’s death, René de Thory fell in love with Anne d’Assé, wife of François de Villeprouvée, Baron of Trier, who died under suspicious circumstances in January 1530. Questions arose that perhaps Anne’s husband was poisoned. Since poems written by René about his love for Anne were discovered, the two were accused and tried for murder; however, they were not convicted and secretly married in March 1530.

While the windows of the chapel honor the first Lady of Boumois, de Thory had the chapel consecrated as the Chapel of St. Anne by the priest at Saint-Martin-de-la-Place on March 15, 1546 in honor of his second wife, Anne. At René de Thory’s death in 1565, Boumois was left to his wife and his son, Antoine de Thory.

The estate stayed in the de Thory family until sold in 1607, and then changed owners repeatedly over the next 300 years including a sale of the chateau’s furnishings in 1833. At the end of the nineteenth century, the architect and designer Stanford White obtained the five stained glass panels. He was known for decorating in the neo-Gothic style favored by his wealthy clientele—the nouveau riche seeking to create the wealth of the Old World in their American homes. After White’s death, newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst acquired the panels in 1907. Later, through a gift purchased by Mr. and Mrs. Walter Lee from French & Co, M&G received the windows in 1956.

The Windows’ Imagery

Stained glass as an art reached its peak in the Middle Ages; the cathedrals with the increased buttressing allowed for more windows, whose colored beams of light created beautiful effects in the sanctuary by illuminating the space and using light to “paint” the Scriptural stories. Jacques DuPont explains “this form of painting is less an ornament than the lyrical expression of a transcendent world” as stained glass creates “an atmosphere befitting the House of God, the Light of the World.”

Having a complete set of windows from this period is rare, and the imagery of the central windows is dramatic. In this crucifixion scene, the cross bearing Christ’s suffering body with five bleeding wounds stands above a fountain in which Adam and Eve are bathing—being cleansed of their sin; Christ’s blood then flows into a larger pool representing the forgiveness provided for all mankind—“whosoever will” may be cleansed and made righteous through faith in Christ’s sacrifice. Above Christ is a door perhaps referencing Christ’s own words, “I am the door…. I am the way, the truth, and the life; no man cometh unto the Father, but by me.”

Interestingly, the four fountain heads are the symbols in art for the four evangelists: an angel (Matthew), a lion (Mark), an ox (Luke), and an eagle (John). The designer may have referenced the iconography of paintings in the region like the Fountain of Life at the Calvet Museum in Avingnon or a slightly different version at Saint Mexme in Chinon. Emile Male in his book Religious Art in France explains the symbolism of the four fountain heads, “This is an ingenious way of saying that the miracle of forgiveness has the Gospels as authority, that is to say, the Word of God Himself.” These windows present a beautiful representation of several doctrinal truths, such as the love of Christ, the power of His sacrifice to cleanse sin, and the fulfillment of His promise to Adam and Eve.

William Cowper, eighteenth-century poet, captured the same visual truth through language: There is a fountain filled with blood drawn from Emmanuel’s veins; and sinners plunged beneath that flood lose all their guilty stains.

Erin R. Jones, Executive Director

Published in 2018

The Martyrdom of St. Perpetua and St. Felicitas

Oil on canvas, Signed and dated, Félix Leullier, 1880

Félix Louis Leullier

French, 1811–1882

In this arresting example of the nineteenth-century Romantic style, Felix Louis Leullier uses all the forces of paint and position to create a gruesome depiction of one of the most famous martyrdoms of the Christian church. Little known outside of France, Felix trained with Antoine-Jean Gros, renowned for his depictions of some of Napoleon’s famous battles: Battle of Arcole, Napoléon on the Battlefield of Eylau, and Battle of Abukir. Gros leaves little to the imagination in the spheres of conflict and conquest, so it is no wonder that his student, Felix, would choose to depict a martyrdom in a context resembling the twisted forms often found on a battlefield.

The painting’s setting is the Roman Amphitheatre in Carthage, the North African center of Christianity in the early centuries following Christ’s death and resurrection; there is little more than an outline remaining today of the prominent structure that seated 30,000. Although Felix most likely did not travel to that part of the world, he could have easily participated in a Grand Tour, a customary excursion in the 18th and 19th centuries for men coming of age, to see and learn from the culture and histories of antiquity. Such a broadening and experiential trip included significant time in Rome, where the Colosseum was a chief point of interest and which is very similar to Carthage’s own great amphitheater. The combined influence of travel and exposure to prominent depictions like Granet’s Interior View of the Colosseum in Rome, 1804 and Towne’s The Colosseum, 1781, Leullier opts to create only a faint representation of an outdoor arena.

On March 7, 203 AD, under the rule of the Roman emperor, Septimius Severus, the noblewoman Vibia Perpetua, was executed with her handmaid, Felicitas, and fellow catechumens, Revocatus, Saturninus, and Secundulus. Just a few years earlier in 197 AD in his treatise Apologeticus, Tertullian had posited that “the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church.” As providence would have it, Tertullian himself was eyewitness and later chronicler to the gripping event portrayed in this work.

In addition to Tertullian’s account and Perpetua’s own prison diary, Passio Perpetuae et Felicitatis, in which she captures much of the detail up until the hour of her entrance into the arena, many attempts to present the event have been created in various media formats. It is contained in older volumes like Foxe’s Book of Martyrs (1563), as well as in more recent accounts like Thomas J. Heffernan’s The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity (2012). It is visible in paintings, drawings, mosaics, stained glass and illuminated manuscripts like Menologion of Basil II; and it has been presented in investigative journalism in the PBS Frontline series, From Jesus to Christ (1998).

Leullier’s visual rendering is indeed grand both in presentation and size, measuring nearly seven feet high by nine feet wide. Though literary works relate that Perpetua and Felicitas were martyred separately from the men, Leullier deviates from the historical account and instead depicts the entire company—the martyrs, the men that assaulted them, and the many animals that mauled them. By placing the massacre in the forefront of the work, the purity and testimony of these Christians’ story cannot be ignored.

Bonnie Merkle, M&G Database Manager and Docent

For further enrichment:

-

Visit the M&G’s Bowen Collection of Antiquities where Roman antiquities are displayed.

-

Visit the Museum of the Bible where 30 objects from the Museum & Gallery collection are exhibited, including a first century Roman funerary altar.

Published in 2018

The Ascension

Oil on canvas, 1883

Gustave Doré

French, 1832–1883

Louis Auguste Gustave Doré (1832-1883) is justly known as the greatest illustrator ever. His genius was recognized when he was a child, and his photographic memory allowed him to include minor details often overlooked by others.

He began his prolific professional career at the age of 15 as an illustrator for the humorous magazine Journal pour Rire. During his relatively short life, he produced at least 8,000 wood engravings, 1,000 lithographs, 700 zinc engravings, 100 steel engravings, 50 etchings, 400 oil paintings, 500 watercolors, 800 mixed-media sketches, and 30 major works of sculpture.

While many admire Doré’s work, few people actually recognize his art, even having grown up seeing his pictures. His New and Old Testament illustrations became the most widely used and familiar images in twentieth-century Bible literature. He also created several large series of engravings for classics including The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Don Quixote, Paradise Lost, Perrault’s Fairy Tales, The Divine Comedy and more.

Historically, illustrators have received little recognition for their artistic careers compared to their “fine art” counterparts. Doré was equally productive in creating oil paintings and sculpture, and his greatest ambition was to be respected primarily for his painting career; however, he is best remembered as an illustrator.

M&G’s Collection has two of his most important religious paintings—The Ascension and Christ Leaving the Praetorium, both completed in 1883.

As is typical of many artists, Doré created multiple versions of his works. His first version of The Ascension was completed in 1879 and measures almost twice the size of M&G’s painting, which is an imposing 11’ 11” tall by 7’ 8” wide! The original Ascension hung with other religious works in the German Gallery of London (later called the Doré Gallery) where the great preacher Charles Haddon Spurgeon frequented and encouraged his congregation to visit.

Sketches that Doré made while riding the newly invented hot-air balloon with his photographer friend, Felix Nadar, probably inspired The Ascension’s aerial perspective—the viewer is on the plane of the ascending Christ with the disciples small and distant standing on the ground. The rich greens and golds in Doré’s thick brushstrokes create excitement and energy at the end of Christ’s earthly ministry and the beginning of His heavenly role. The angels’ response in Acts 1:11 voices the painting’s story, “Ye men of Galilee, why stand ye gazing up into heaven? This same Jesus which is taken up from you into heaven, shall so come in like manner as ye have seen him go into heaven.”

John Good, Docent and Security Manager

Erin R. Jones, Executive Director

Published in 2018

Christ on the Sea of Galilee

Oil on canvas

Unknown French

Click on links for additional reference information.

This dynamic seascape by a seventeenth-century French painter bears a striking similarity to a work done by a renowned Dutch master of the same period, Rembrandt van Rijn. Until the modern concepts of copyright and intellectual property, most artists of the past eagerly learned from the creative ideas and innovative troubleshooting of both those before them and their contemporaries. Part of an artist’s training involved painting copies of famous works of art or that of their master (the teacher they were apprenticed to or worked under). The diagonal composition, dramatic lighting, textures, and even to some degree, the figures in this M&G work are clearly reminiscent of Rembrandt’s Storm on the Sea of Galilee (below).

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) was born in the Netherlands, “a land of winds and water.” Located on the North Sea, twenty-five percent of the land is at or below sea level with the highest point (Vaalserberg) only 1053 feet above. Over the centuries, this geography has shaped both the nation’s history and the temperament of its people. For example, during the seventeenth century raging sea storms and lowland flooding often threatened life and livelihood, but Dutch ingenuity and resilience turned these formidable obstacles into valuable resources. (For more detailed exploration download the National Gallery of Art’s informative resource Painting in the Dutch Golden Age.)

In light of Rembrandt’s birthplace, it’s interesting that he painted only one seascape. Regardless, the dynamic composition and nuanced atmospheric beauty of his Storm on the Sea of Galilee reflects an intimate knowledge of storm-tossed seas. Rembrandt was only 27 when he painted this work, and art historians have speculated that the choice of subject indicates a youthful preference for action-packed scenes. Whatever his motivation, the scene clearly adumbrates the dramatic chiaroscuro and nuanced visual texture that would become a hallmark of his work.

Sadly, we are limited to experiencing the work through reproductions. On the night of March 18, 1990, two thieves dressed as police officers entered the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, bound the museum’s security guards, and made off with thirteen of the gallery’s prized masterworks, including Rembrandt’s famous seascape.

Artists today are still honing their skills by studying and copying such masterworks. As contemporary artist Lisa Marder acknowledges, it is “one of the tried and true techniques of classical art training.”

Donnalynn Hess, Director of Education

Published in 2017