Luca Giordano, a child prodigy, would become one of the Baroque era’s most noted Neapolitan artist. M&G has at least three of his works including The Triumph of Miriam.

Tag Archives: Italian art

Roughly the same size, these beautifully rendered panels painted by Pietro Negroni most likely came from an altarpiece in a convent church in the Calabrian city of Cosenza.

This vibrant painting depicting Abraham and his family’s departure for Canaan features many of the details that the Bassano family were skilled in painting.

Madonna and Child with Angels

Tempera and oil on panel

Master of the Greenville Tondo

Umbrian, active late 15th century

This mystery painting was once attributed to the young Umbrian, Raphael as possibly one of his early works (Giuseppe Fiocco, 1937), which could “aid in the studies of the formation of Raphael’s personality” (Mario Salmi). Then, it was suggested as characteristic of Raphael’s teacher in Umbria, Pietro Vannucci, called Perugino (William Suida, 1941 and Wilhelm von Bode, 1921). But it was the great historian Federico Zeri in 1959 and later followed by Everett Fahy, former Metropolitan Museum of Art curator and Director of the Frick, who suggested a different old master entirely.

This tondo (Italian for “round”) is puzzling, but understanding the cultural context of patronage, traditional artistic training, and the workshop setting can help explain some of the mystery.

In the Middle Ages through the early Renaissance, workshop practice was the only common form of artistic instruction in Italy beginning with the religious orders, monasteries, and convents. The Trades (sculptor, mason, architect) were taught from father to son or from an older family member to a younger. Formal apprenticeships emerged in the 13th century in the context of the craft guild system when workshop or bound apprenticeship became a fully regulated system for lay artists. Then, during the 15th century, the dislike for the guild system’s restrictions and process led to an adapted concept of artistic training, called the Academy. The specific training process for artists is further developed in the article about M&G’s painting, A Sibyl by female Old Master, Ginevra Cantofoli.

Throughout all of these training methods to become a master of one’s own workshop, imitation was the most important component of artistic training. Master painters employed a workshop of assistants to copy or paint in his style and to help meet the incoming demand of commissions by patrons. These points are critical to understanding why it is difficult to attribute a specific artistic personality to today’s enduring Old Master paintings. Besides, most painters well into the late 1400s and early 1500s did not autograph their finished works, and finding the original documents commissioning paintings can be challenging.

However, when the artist is unknown, yet there is an entire group of works that look to be by the same master’s hand, the experts (as in this case) will suggest a pseudonym—create a name for the artist after the place or location where his best or most representative work resides. Zeri and Fahy chose M&G’s painting as the namesake for the painter, “The Master of the Greenville Tondo,” meaning this tondo in Greenville, SC.

According to historian Carrie Baker, this painter, subject, and style reflect the “prevailing visual tastes of the period.” Workshop practice utilized multiple assistants and collaborative work to fill commissions that looked like the master’s hand. The assistants were all skilled artisans but working for the key master. Not knowing the assistants’ names isn’t an issue as this was their occupation: to reproduce works at the request of clients in the consistent style of the master to meet customer expectations. Today, we can photograph and print our favorite originals, but then artists could only copy and repeat. Works like M&G’s Madonna and Child with Angels reflect a popular subject and shape of the period, and providing paintings like M&G’s at a client’s request was the master’s way of “positioning . . . his workshop at an economic advantage.”

Many of the masters and their assistants were truly “Renaissance” men—able to tackle the design of many things, not just paintings but manuscripts, reliquary, sculpture, fabrics, architectural features, etc. The anonymous artist as Baker notes, “was probably an active participant of a working-class system of many trades.” The artist is unknown, but by comparing similar characteristics, experts have connected at least 32 works as having come from this same artist’s hand found in places including Pancole, Italy, the Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg in Florida, Princeton University Art Museum in New Jersey, the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, and the Estensi Gallery in Modena, Italy.

Regardless of this painting and many others not being attributed to a specific, known personality—such as a respected influencer like Perugino or a major name of the Renaissance like Raphael, this master’s work was just as valuable in shaping Umbria’s artistic identity. And, more than that, our painting is shaping the estimation of our own community through the designation “Master of the Greenville Tondo”—bringing honor and recognition to the city of Greenville throughout the world where other works by this unknown master are displayed.

Erin R. Jones, Executive Director

Published 2025

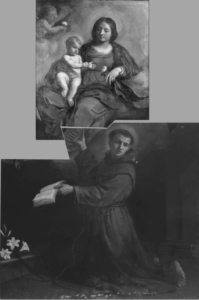

Scenes from The Annunciation: God the Father in a Glory of Angels, St. Gabriel the Archangel and The Virgin Annunciate

Oil on canvas

Francesco Montemezzano

Venetian, c.1540-after 1602

In museum collections, including the Museum & Gallery, there are paintings that were once part of a larger narrative, but now stand as individual works of art. These pieces, usually parts of large altarpieces, have been reduced in size for various reasons such as damage to the whole, for profit, or to fit a new arrangement. Very few that have been broken up have managed to stay together. Francesco Montemezzano’s The Annunciation is one of those lucky few.

At first glance in the galleries, you may notice a similar velvety color palette and free brushwork but may not realize they are one of a whole. If not for the close arrangement in display, one may not be able to see the full image. Originally in a horizontal format, the painting was altered sometime in the seventeenth century to fit a vertical, architectural enframement. Despite this physical cropping, we can still see the theme of the annunciation.

The annunciation is a common subject portrayed in Christian art. The moment is recorded in Luke 1:26-38 where Gabriel informs Mary that she will fulfill the prophecy of Isaiah 7:14 promising “a virgin shall conceive and bear a Son, and shall call His name Immanuel.” This theme became very popular in fifteenth-century altarpieces and were reinterpreted by artists throughout history such as Fra Angelico, Leonardo da Vinci, Botticelli, Caravaggio, Peter Paul Rubens, and John William Waterhouse. Each artist put their own spin on the theme, reflecting the stylistic ethos of the time and the artists’ own taste, but there are common elements.

Mary, Gabriel, and a dove are the main figures. Sometimes they are outside in an hortus conclusus or “enclosed garden,” and other times they are cloistered inside, symbolizing Mary’s chastity. Lilies are usually present, carried by Gabriel or somewhere in the composition, further emphasizing Mary’s purity as a virgin. Mary is commonly shown in prayer with a prayer book or missal kneeling at a prie-dieu. A dove or beam of light usually represents God’s blessing on Mary as His chosen handmaiden or the symbol of immaculate conception.

With this brief background, Montemezzano’s Annunciation stands out. We can see architectural elements throughout the three paintings and a possible garden behind Mary. Was this Montemezzano’s nod to the hortus conclusus? And where is the dove or beam of light that is often shown? Because of its fragmented state, we may never know exactly what the artist designed. However, Montemezzano did include one unique figure in this Annunciation—God the Father. Very few depictions of the annunciation include a physical God the Father, most only show his messenger Gabriel and the dove.

There are actually two other annunciation scenes in M&G’s collection that show God the Father in physical form (one found in galleries 4 and 10). Here, in Montemezzano’s work, God the Father is shown breaking through clouds and the architectural ceiling, symbolizing His passage into the earthly realm. Despite the unique inclusion of God the Father, His presence fits the annunciation theme perfectly. It is a foreshadowing of another part of the Trinity, Jesus, coming into our world to dwell with us as told by Matthew 1:23, “Behold, a virgin shall be with child, and shall bring forth a son, and they shall call his name Emmanuel, which being interpreted is, God with us.”

The Annunciation reminds us of promises fulfilled, how a Savior will dwell with us and come into this broken world to make us whole. While this painting will never have that opportunity to be truly whole again, we as believers are reminded of that promise for us this Christmas season.

KC Christmas Beach, M&G summer art educator

Published 2024