St. Michael the Archangel Overcoming Satan

Giovanni Andrea Sirani

Below the image, click play to listen.

Enjoy this series of segments highlighting Picture Books of the Past: Reading Old Master Paintings, a loan exhibition of 60+ works from the M&G collection. The exhibit has traveled to The Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C. and the Orlando Museum of Art in Florida.

It is unusual to find a complete altarpiece from the late Gothic era, but this beautiful triptych (or three-paneled altarpiece) is still intact.

Oil on panel, c. 1529–30

Florentine, 1486–1530

Andrea d’Agnolo grew up in Florence and was nicknamed del Sarto meaning “of the tailor” after his father’s profession. Like other early Renaissance artists, he initially trained with a goldsmith, then studied under a series of three separate painters until he began producing his own works in 1506. He spent most of his life in Florence—except for a visit to Rome and a brief stint as court painter to King François I at Fontainebleau in 1518.

As the son of a tailor, del Sarto’s works reveal a unique understanding and love of fabrics—even seen in his 1517-1518 Portrait of a Young Man in London’s National Gallery, which may be a self-portrait (on right). Notice the finishes of the puffed sleeve, ruched white undershirt, and the vest’s seam at the shoulder.

As the son of a tailor, del Sarto’s works reveal a unique understanding and love of fabrics—even seen in his 1517-1518 Portrait of a Young Man in London’s National Gallery, which may be a self-portrait (on right). Notice the finishes of the puffed sleeve, ruched white undershirt, and the vest’s seam at the shoulder.

Andrea was also influenced by his contemporaries who outlived him: Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael. Once these masters left Florence for other parts of Italy, Andrea became Florence’s leading artist in the early 1500s. He is overlooked in art history; yet he is equal in skill and quality to the three greats, and his works are beautiful and still revered today. Julian Brooks, curator of drawings at the Getty, recognizes del Sarto as the “revolutionary engine of the Renaissance and the transformer of draughtsmanship” due to his careful and creative preparatory drawings, a practice which inspired the next generations of artists to follow.

However, he has been underappreciated, even to the point of his students overshadowing him to become famous including Rosso Fiorentino, Jacopo da Pontormo, and Giorgio Vasari, biographer of contemporary Renaissance artists. Vasari records details about his teacher as related to M&G’s work. A Florentine charitable organization for plague victims, the Company of St. Sebastian commissioned Andrea del Sarto to paint a picture of St. Sebastian, the patron saint for plague victims. He became a member of the Company in February 1529, perhaps as a result of negotiations surrounding the commission. Ironically, shortly after completing the painting in 1530 during Florence’s plague epidemic, del Sarto died from the plague at 44 years old.

Several 17th-century documents list the original St. Sebastian as the property of the Company of St. Sebastian. Publications in 1759 and 1770 mention that the painting moved to the Pitti Palace in Florence. By the early 19th century, writers could no longer trace the location of the original painting—apparently it was removed from the Pitti Palace and lost.

M&G acquired St. Sebastian in 1970 from the former great British collection of the Cook family. In 2005, the National Gallery of Canada requested St. Sebastian to participate in an exhibition, and we sent our work in advance for study and conservation. The conservator Stephen Gritt found, “In its materials and construction, the painting is entirely consistent with one from Sarto’s workshop. The complete absence of any change in the design from the drawing stage on the panel through to the painting would indicate perhaps that the design had reached a point of satisfactory refinement by the time this version was produced. While this may mean that some artist other than Sarto could have painted the work, it does not exclude his participation in its production as a supervisor.”

Regarding del Sarto’s workshop practice, Julian Brooks notes that “Andrea would have been closely involved in the production of all versions, or at least those produced in his workshop during his lifetime, and these were produced side by side in the studio.” He also made, used, and reused partial cartoons.

It is difficult to confidently confirm if M&G’s St. Sebastian is the missing painting by the master, thus the current attribution, studio of Andrea del Sarto. At the least, someone very close to del Sarto painted the work. Found in Italy, Spain, England, and Austria, more than 10 other variants of the St. Sebastian exist. Even so, M&G’s is considered by specialists as the “best surviving reflection of the original.”

Erin R. Jones, Executive Director

Published 2023

Tempera on panel

Florentine, active late 15th century

In the 15th century, Florence enjoyed a robust cultural and economic environment. One prominent idea of the era was the rediscovery of the circle and the variety of ways it was used. It may be somewhat humorous in our current culture to recognize that a simple shape could dominate life, but the circle did.

The Renaissance was about advancement—an era full of discoveries. Dias, da Gama, Columbus, and Vespucci found places previously unknown through geographical exploration of our planet, understood then to be round instead of flat. Rediscovery of Greek and Roman mathematical perfections included the circle. The shape was incorporated into architecture in a variety of public and private buildings in Florence. The circle became a symbol of God, the universe, and heaven. Between late 1430 to early 1450, artists began using the circle as part of their painting design in a format called tondo, the Italian word for round.

As a spiritual symbol, the circle became a means of representing the patron saint of Florence, John the Baptist. He was often depicted as a youth, an example to the young people of Florence. Before the Renaissance, paintings focused on individual depictions of saints and biblical characters; however, artist Fra Filippo Lippi is credited with being one of the first to paint John the Baptist together with Mary and the infant Christ in the 1450s. Additionally, Lippi was the first to paint the figures worshipping the Christ Child in adoration as seen in his work, the Annalena Adoration in the Uffizi, Florence. This new subject was the beginning of a popular focus in the late 1400s and well suited to the tondo format.

Filippo Lippi had a bustling workshop with many apprentices including Pesellino and Botticelli. As a favorite of the Medici, Lippi fulfilled numerous private and public commissions, including a Medici tondo now in the National Gallery. While Botticelli is credited with making the round format popular in the late 1400s, Lippi’s studio and apprentices created tondi and essentially mass-produced paintings depicting Mary and John the Baptist adoring the Christ Child to satisfy the public demand.

The Medici family was partly responsible for the popularity of tondi because these round paintings became not only a status symbol of wealth, but also were of spiritual significance in private, devotional settings. To have an object of art that the Medici possessed was a means of connection to them. Tondi existed in the homes of wealthy Florentines and public spaces and soon became popular in other Italian cities. They were not commonly used in churches since they were smaller.

The creator of M&G’s tondo, Madonna and Child with St. John the Baptist and an Angel, is enigmatic. Scholars have been unable to attribute a specific artist, but the work seemed influenced by Pier Francesco Fiorentino yet not painted by him. Hence, the designation of “Pseudo.” However, careful study of the work indicates that its construction predates the surge in popularity of tondi in the 1480s. M&G’s painting is one of the earliest surviving tondi produced after Fra Filippo Lippi’s initial exploration of the adoration subject—a strong representative of the Florentine tondo tradition.

The painting’s details include a unicorn in the background, which is a symbol of Mary’s purity along with the white lily. Her adoring the Christ Child in a country landscape setting may be based on St. Bridget’s Revelations. The halos reveal the influence of naturalism prevalent in the Renaissance style. While the halos of Mary and the angel are typical of the flat Gothic style, the foreshortened, elliptical halo of John the Baptist is shown from a three-dimensional perspective.

As a “window into heaven,” M&G’s tondo has delighted viewers since entering the collection in 1951—the museum’s inaugural year.

John Good, M&G volunteer

Published 2022

White Oak with Ivory and Ebony

Italian, 17th or 18th century

Donated to the Museum & Gallery in 1973, this beautiful antique was described merely as a “Chest of Drawers,” believed to be Dutch, from the late 16th century. During the cabinet’s history in the collection, the mirrored base on which it was first displayed was swapped out for the more suitable, baluster-turned legs on which it currently stands (though not original).

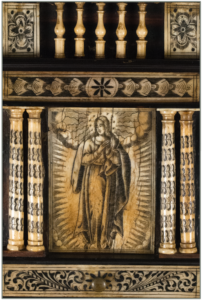

The Cabinet is substantial, standing five-and-a-half feet tall (including the base), almost four feet wide, and 15 inches deep. Beyond that, not much has been known about the Cabinet beyond its style (Baroque) and composition (finely detailed ebony and inlaid ivory veneers on the face of oak drawers and doors). Three etched ivory plaques, possibly based on engravings, grace the front of the piece. These picture the Apostle John on the left lower door and John the Baptist on the right. Both doors are lockable with the original key. The central, etched ivory plaque depicts Mary, the mother of Christ, framed by three-dimensional carved ivory columns to either side.

The Cabinet is substantial, standing five-and-a-half feet tall (including the base), almost four feet wide, and 15 inches deep. Beyond that, not much has been known about the Cabinet beyond its style (Baroque) and composition (finely detailed ebony and inlaid ivory veneers on the face of oak drawers and doors). Three etched ivory plaques, possibly based on engravings, grace the front of the piece. These picture the Apostle John on the left lower door and John the Baptist on the right. Both doors are lockable with the original key. The central, etched ivory plaque depicts Mary, the mother of Christ, framed by three-dimensional carved ivory columns to either side.

While those details of the Cabinet are basic, they communicate a significant amount about the furniture’s place and date of origin, as well as the type of owner it was likely built for. First, however, it’s helpful to know some of the history of cabinets as furniture.

Cabinets utilizing ebony wood date back at least to Egyptian times, like several discovered in Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922. Such dedicated, highly decorated storage furniture demonstrated the status and wealth of its owner. Over intervening centuries of adaptation, storage and collection cabinets proliferated in both Eastern and Western cultures, though only the wealthy could afford the most finely constructed and exotically decorated pieces.

Ebony wood was a favorite material, sourced only from ebony tree varieties in western Africa, India, and Indonesia. Because ebony was scarce, craftsmen learned to shave and apply thin veneers of the jet-black ebony heartwood on top of readily-available wood species used for the rest of the object. The dark background was then inlaid with contrasting materials such as ivory, metal, lighter woods or semiprecious stone.

As early as 1566, the inventory of a room in the Ducal Palace of Mantua (in northern Italy) lists an ebony cabinet with inlaid ivory panels. Though the Ducal version was likely made 150-plus years prior to M&G’s Cabinet (dating sometime in the late-17th or early 18th century), both share similar intricate ivory inlay and metal filigree.

Piecing together that general history helps in suggesting the origins and ownership of M&G’s Cabinet on Stand The condition of the ivory and construction methods distance the cabinet from the 19th-century revival of ebony and ivory furnishings.

However, the ivory demonstrates some discoloration and shrinkage from age, while the cabinet frame, back, and drawer construction seem more consistent with an earlier date. The white oak used as the secondary wood was common only in northern Italy (Venice or Milan, but not Rome) and Northern Europe (German, Holland, and Flanders).

The etched biblical figures expressed in the inlaid ivory seem more “lively” and less restrained than is common when artists in Protestant countries present the same figures. That suggests a Roman Catholic country of origin, such as Italy.

Finally, the totality of the Cabinet—exotic materials, time-consuming craftsmanship, and subject matter—indicate a prominent and wealthy patron. The religious subject matter likely indicates that the original owner was a highly-placed churchman, perhaps a bishop, using the cabinet as a way to flaunt both his religious devotion and his prominence/wealth.

Good examples of similarly inlaid antique chests exist. Some of the best examples can be found in the collections of the Victoria & Albert Museum (dating from about 1600), the Museum fur Kunst & Gewerbe (Hamburg, Germany), and some auction sites such as Sotheby’s and Christie’s, as well as high-end antique dealers.

Dr. Stephen Jones, M&G volunteer

Resources

David L’Eglise, partner at Village Antiques at Biltmore

Published 2022