In this beautifully tranquil scene, Michel Corneille includes a variety of traditional symbols highlighting Christ’s sacrifice for our sin.

Tag Archives: Joseph

Baroque Spanish artist Francisco Collantes relies on his considerable skill as a landscape painter to enhance the storytelling power of this Biblical narrative from Genesis 37.

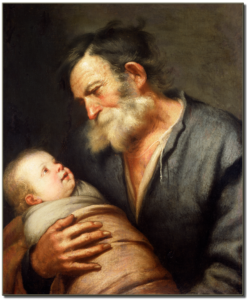

The Return from the Flight into Egypt

Oil on canvas, c. 1712

Giuseppe Bartolomeo Chiari

Roman, 1654-1727

Rome was for centuries the epicenter of culture, art, and religion. At the time of Giuseppe Chiari’s birth, it was also “the scene of a lively debate with a constantly varying interplay of influences, trends, fashions, specialized treatises, and, of course, great masterpieces” (Zuffi, p. 64). At the center of this debate were three artistic movements that Zuffi notes “succeeded one another in a sort of ideal relay race of artistic styles.” The stark naturalism of Caravaggio, the elegant classicism of Annibale Carracci, and the dramatic baroque sculptures and architecture of Gian Lorenzo Bernini would all play a part in making 17th-century Rome—well, Rome!

As president of the Roman Academy Carlo Maratta was keenly aware of these lively debates. Considered one of the most important painters in the latter half of the 17th century, he was much admired for his beautiful frescos and stunning portraits. Although his work evidenced a clear admiration for the classical tradition, several of his paintings also integrated elements of Caravaggio’s vigorous style. David Steel points out that Maratta often “managed to steer a middle course between these two dominant and often contrary trends of baroque painting” (Steel, p. 88).

Maratta was at the summit of his career in 1666 when 12-year-old Giuseppe Chiari entered the great master’s studio. Chiari soon became a star pupil. Over the years, his profound respect for Maratta’s tutelage would not only shape his artistic development but also ensure his future success in a highly competitive environment. When Maratta died in 1713, Chiari took up Maratta’s mantle and became the dominant Roman artist.

Like Maratta, Chiari broadened his appeal by becoming an astute observer and deft practitioner of integrating stylistic trends. Kathrine and William Wallace highlight this skill in their comparative analysis of Chiari’s Tedallini altarpiece with Caravaggio’s Madonna dei Pellegrini [figs. 1 and 2]:

“The statuesque pose of Chiari’s Madonna, the unusually high step on which she stands, the elongated form of the Christ child framed by a white swaddling cloth, and the overall right-triangular composition recall Caravaggio’s Madonna dei Pellegrini. Yet the suggestion is subtle: Chiari has reversed the composition, naturalized the pose of the Virgin, and substituted the more palatable, well-dressed saints for the dirty feet and common character of Caravaggio’s pilgrims. Although inspired by Caravaggio, Chiari’s altarpiece remains distinctly his own. Chiari’s Madonna looks like a person of warm flesh and blood rather than the marmoreal statue of Caravaggio’s Madonna; Christ is an attractive child of sweet disposition as opposed to the enormous and ungainly figure depicted by the older master. Instead of the muted and earthy colors of the Madonna dei Pellegrini, Chiari’s bright hues are immediately pleasing and a welcome contrast to the comparatively dark paintings found on so many Roman altars” (p. 4).

The Return from the Flight into Egypt provides another example of Chiari’s virtuosity and unique style. Here, however, he turns from echoing the past to adumbrating the future. The refined handling of the paint and elegant figural poses pay homage to the classical tradition; however, the playfulness, delicate coloration, and ornamental enrichment mark the transition into the sensuous, intimate style of the rococo movement which emerged in France and spread throughout Europe in the 18th century (Chilvers, 507).

M&G has two works by Chiari on this subject, one titled The Rest on the Flight into Egypt and this rendering titled The Return from the Flight into Egypt. Over the years scholars have found the less traditional title of this 1712 work problematic. However, “the light-hearted, almost celebratory mood” (echoed in the Rococo style) reinforce the idea that here, Chiari intends to highlight the family’s return from rather than flight into Egypt. Regardless of the debate, art experts like Christopher Johns note that this picture may be the best example of Chiari’s work in America.

Donnalynn Hess, M&G Director of Education

Resources:

Baroque Paintings from the Bob Jones University Collection by David H. Steel

Concise Dictionary of Art and Artists, 3rd edition by Ian Chilvers

“Giuseppe Bartolomeo Chiari,” The Art Bulletin, March, 1968, Vol. 50, No. 1 by Bernhard Kerber and Franciscono Renate

“Seeing Chiari Clearly,” Artibus Et Historiae, 2012, Vol. 33, No. 66 by Katherine M. Wallace and William Wallace

Published 2024

Enjoy this beautiful portrayal of the story of Joseph as told through the Museum & Gallery Collection.

Joseph Interpreting the Dreams of Pharaoh’s Butler and Baker

Oil on canvas, signed and dated, 1643

Gerbrand van den Eeckhout

Dutch, 1621–1674

Gerbrand van den Eeckhout, the son of a goldsmith, studied with Rembrandt for five years (age 15-20) and was a “great friend” of the famous artist, according to his biographer. He also continued to imitate his teacher’s style throughout his career, especially in his religious paintings. His first signed painting is dated 1641 (age 20), which probably indicates the time he advanced from student to independent artist. Therefore the Museum & Gallery’s painting, dated 1643, was one of his earliest works. In addition to painting, he worked as an etcher and draughtsman. He never lost interest in his father’s work of goldsmithing, often including precisely painted metal objects in his paintings, as well as producing a book of patterns for ornamental designs for metalworkers. His family’s Mennonite faith influenced his preference for religious subject matter, although he was also known for portraiture and landscape painting.

The biblical story of Joseph is an inspiring one. After being sold into slavery by his jealous brothers and being falsely accused of attempted rape in Egypt, the depicted scene shows him in prison. Because of his trustworthiness, he has been placed in a position of leadership within the prison (notice the keys hanging from his waist) and is interpreting the dreams of two of Pharaoh’s servants. The butler (or person who tasted the king’s wine to make sure it was not poisoned) is shown to the right in fancier clothes with a jug at his feet; he would be pardoned in three days. The baker, however, would be killed in three days. We can see the look of despondency on his face as he learns his fate. Although the butler promised to remember Joseph to Pharaoh, it wasn’t until two years later that a circumstance caused him to remember. After all of Joseph’s trials, he praised God and told his brothers, “you meant evil against me, but God meant it for good” (Genesis 50:20).

The provenance, or ownership history, of the painting begins with a sale in Amsterdam in 1762, just a little over 100 years after its creation. The Dundas family of Scotland purchased it, where it remained by family descent until 1953; it became part of the Collection in 1963.

Published in 2013

Monthly Update

Sign up here to receive M&G’s monthly update and collection news!

EXPLORE More Online Features

Speakers Bureau

We can speak for your retirement group, civic club, church fellowship, or book club. Contact us here or at 864-770-1331.

Support Our Work

Make a Gift to M&G to help our current work and future plans.