ArtBreak: Meet the Collection

Hidden in storage and out on loan, M&G’s European Old Masters have been sorely missed during our preparation to move. Whether this is your first introduction to the collection or a reunion with old friends, come to hear from nationally recognized, engaging specialists from across the country as they introduce the richness and renown of the internationally respected Bob Jones Collection. It’s time for Greenville to meet… its Collection!

Presented by Glenn & Joyce Bridges with additional support provided by Hughes Investments

Dates: 3rd Tuesdays at Noon, during academic year

Location: The Davis Room, Dixon-McKenzie Dining Common on the campus of Bob Jones University

Parking: reserved spaces will be available in M&G’s parking lot.

Note: Aramark Catering will provide a Deli Bar with the following spread: sliced oven-roasted turkey, roasted beef, and ham, and tuna; a cheese and relish tray; a variety of baked breads and rolls, two green salads, chips, assorted cookies, and beverages.

Cost:

- Member without lunch: FREE

- Member with lunch: $17.00

- Non-member without lunch: $6.00

- Non-member with lunch: $19.00

To Register, click on the dates below.

Fall Lectures:

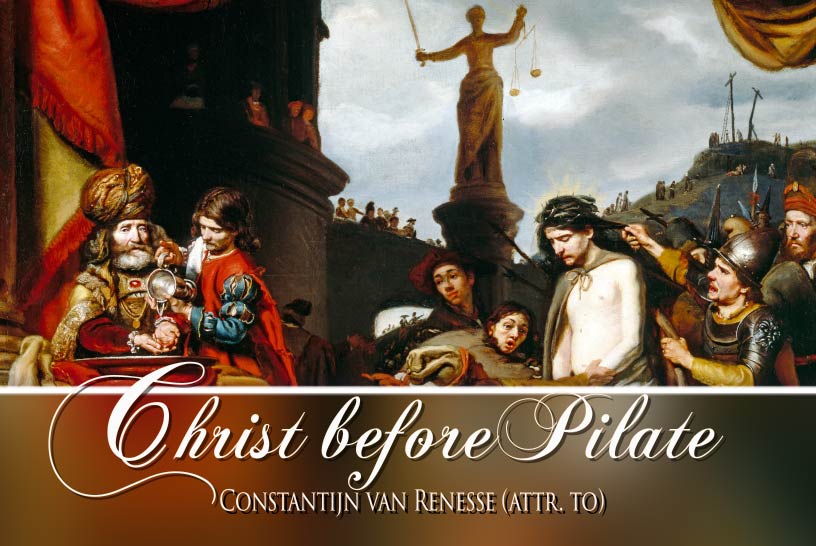

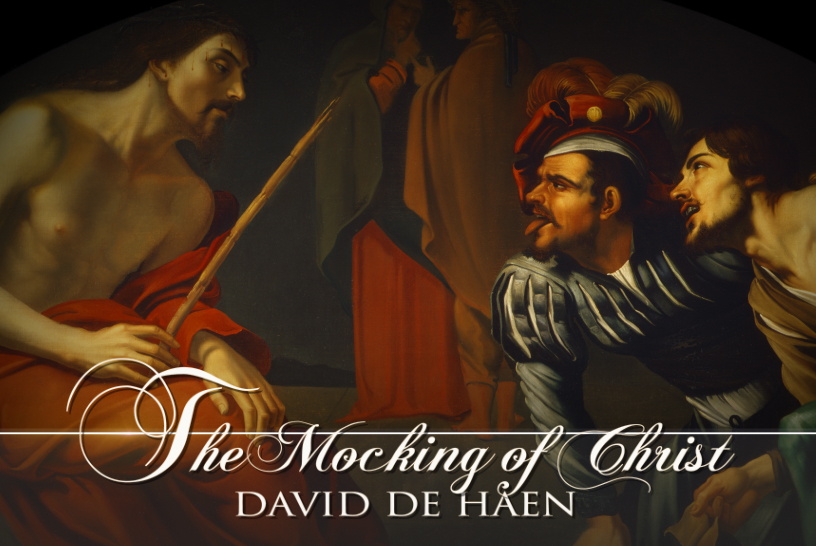

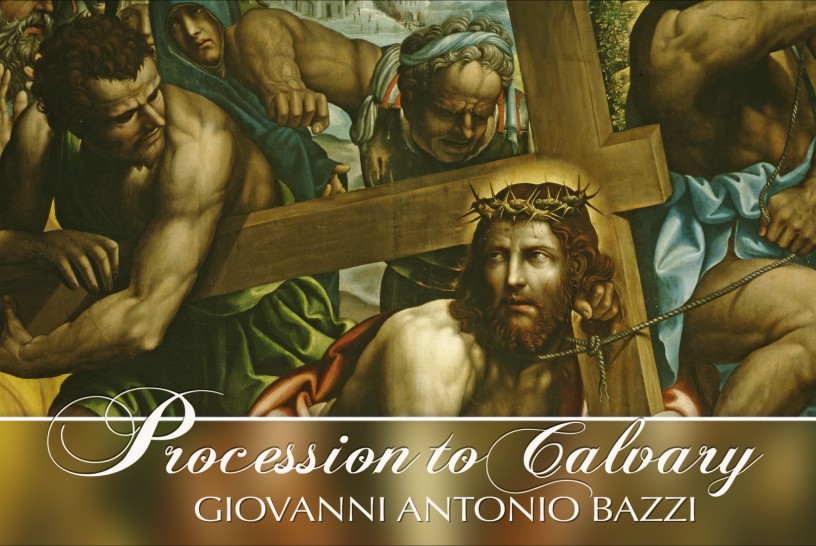

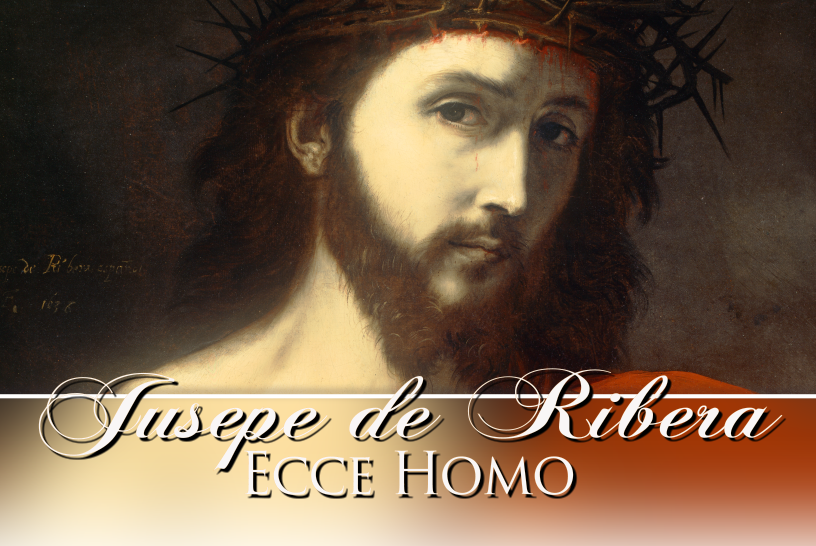

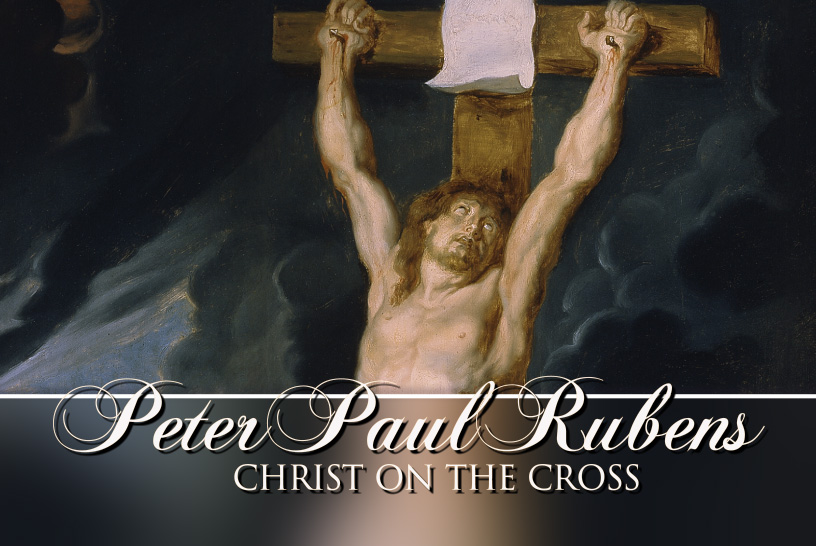

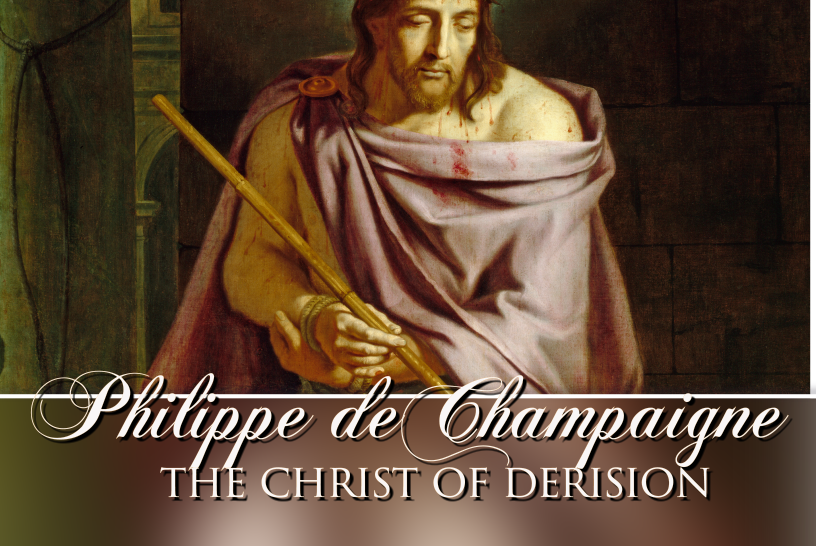

October 15: Going for Baroque: Collecting 17th-Century Paintings in 20th-Century America

American collectors loom large in the revival of “Baroque pictures.” In the 17th century, artists like Guido Reni, Luca Giordano and Rembrandt were huge, international artistic sensations, but by the Victorian era critics like John Ruskin eviscerated their reputations. Specialist Richard P. Townsend will look at the extraordinary people who saw past these prejudices and made extraordinary discoveries—and found extraordinary value—at auction and with dealers. Townsend will examine legendary collectors such as John Ringling the circus king, museum directors William Valentiner and Chick Austin, construction magnate Luis Ferre, robber barons and financiers like Henry Clay Frick and J. Paul Getty and of course, Bob Jones Jr.

November 19: Luminous Devotion: The Fountain of Life Window from the Château of Boumois

Register for lunch by Noon on Friday, November 8.

Emory art historian Professor Elizabeth Pastan and Metropolitan Museum of Art Conservator Drew Anderson join forces to examine the Museum & Gallery’s resplendent early 16th-century Fountain of Life window.

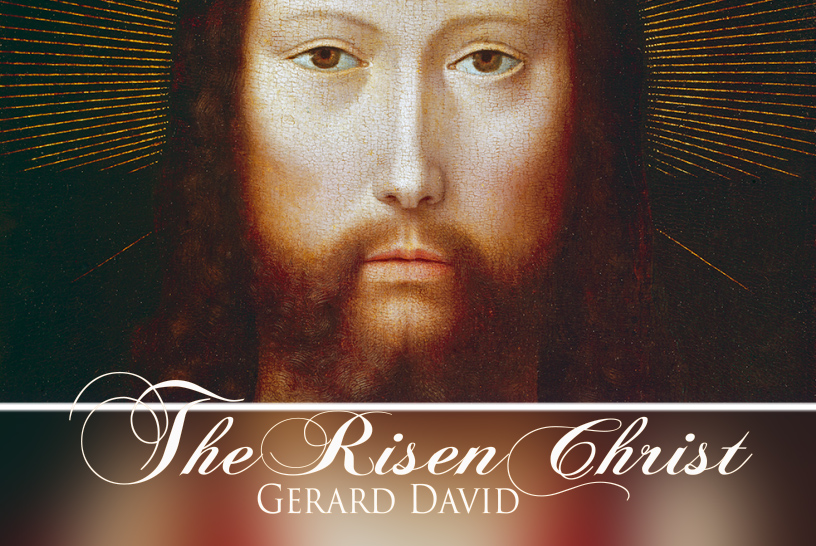

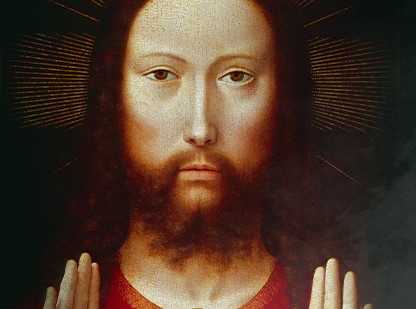

December 17: Communal Worship, Private Devotion, Art, and Politics: Contemplating the Icon Collection of the Museum & Gallery at Bob Jones University

Register for lunch by Noon on Friday, December 6.

Dr. Asen Kirin, professor at the University of Georgia and Parker Curator of Russian Art at the Georgia Museum of Art will focus on different examples of devotional images created for ecclesiastical or domestic use. M&G’s Russian icon collection will demonstrate both the instances of high artistic accomplishment and cases when images reflect the political ideology of the late medieval era.

Spring Lectures:

February 18

Register for lunch by Noon on Friday, February 7.

March 18: Early Renaissance to 19th-Century Craftsmanship

Register for lunch by Noon on Friday, March 7.

From storage cabinets to travel chests to serving credenza, David L’Eglise from Village Antiques in Asheville will share highlights and reveal history of the functional and decorative found in the furniture collection of the Museum & Gallery.

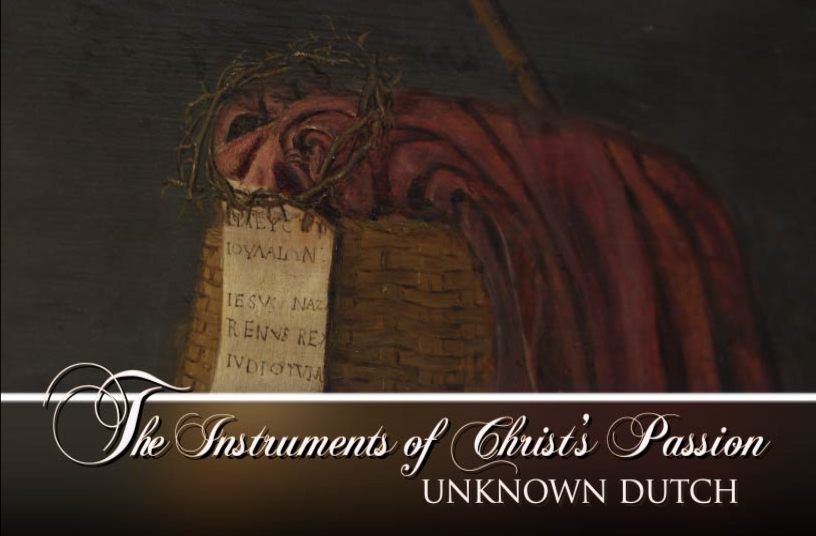

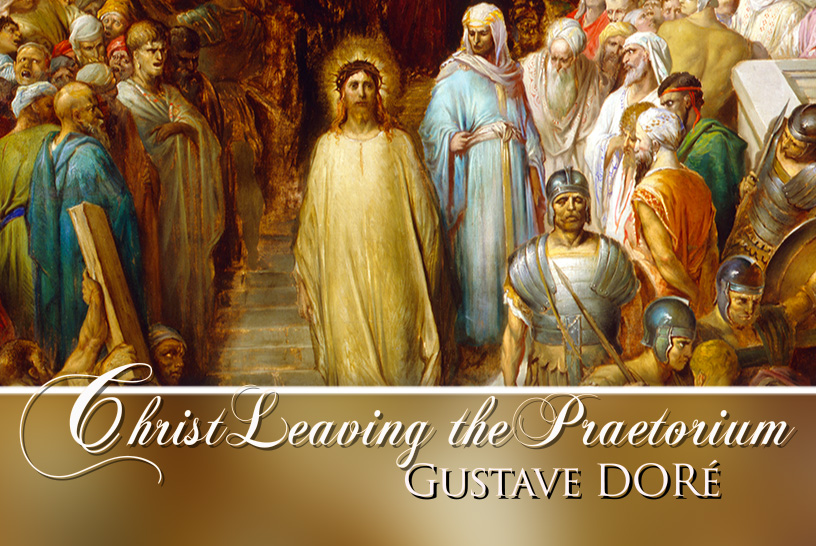

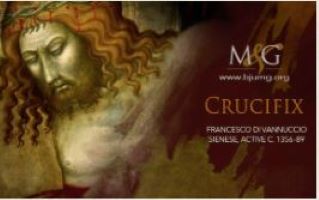

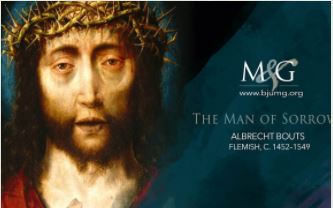

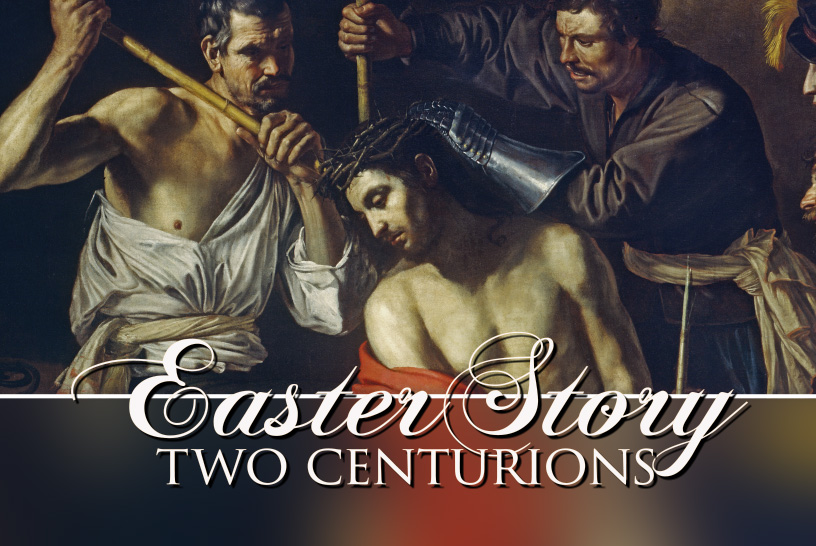

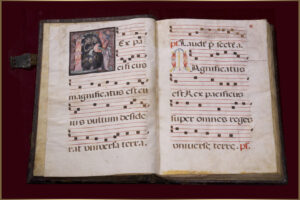

April 15: Devotional Art in Medieval and Renaissance Europe

Register for lunch by Noon on Friday, April 4.

Taking M&G’s monumental painted cross by Francesco di Vannuccio as a point of departure, Dr. Lyle Humphrey, associate curator of European art at the North Carolina Museum of Art, will discuss the role of art in religious practice in late medieval and Renaissance Europe. Humphrey will examine the evolution of both imagery and artistic formats through three centuries, from about 1350 to 1520.