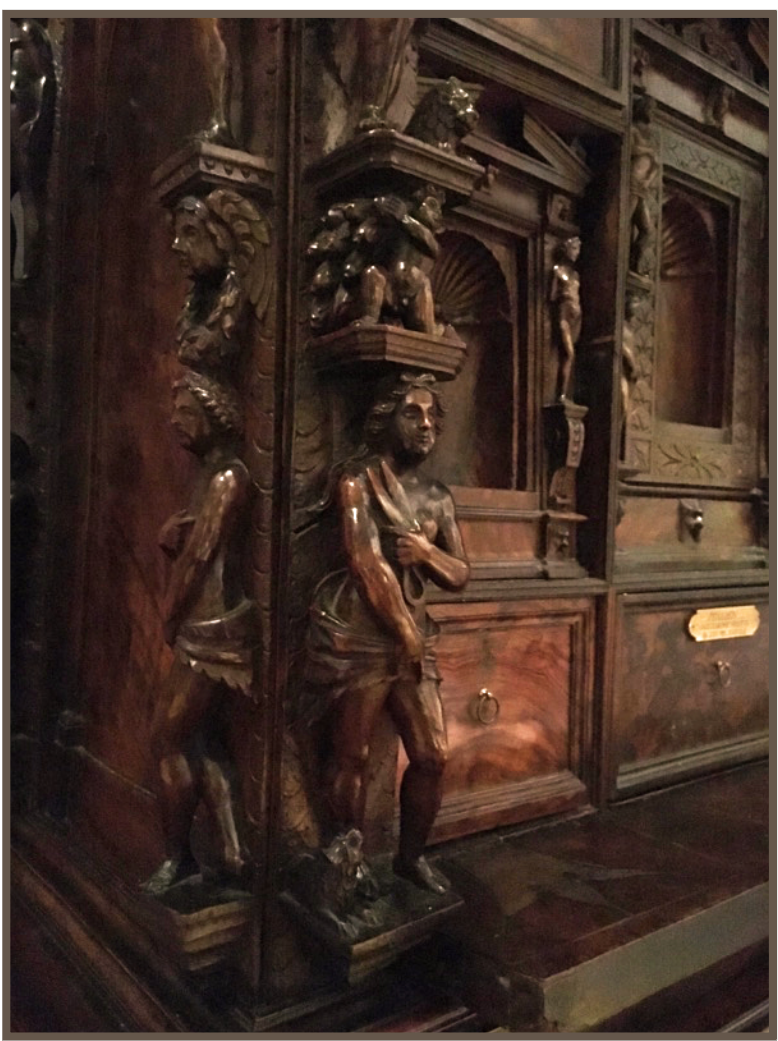

St. Ambrose and St. Augustine

Oil on panel

Gaspar de Crayer

Flemish, 1584–1669

Gaspar de Crayer spent much of his career as a painter for the elite of the Spanish Netherlands. In addition to numerous portraits, he completed a large number of altarpieces. Matthias Depoorter notes: “The motifs that he borrows from the work of Rubens are so specific that people suspect that he had contact with Rubens’s studio.” For example, the figurative influence, coloration, and brushwork of Rubens’s Entombment (figure 1) is also clearly evident in De Crayer’s Deposition (figure 2).

Depoorter goes on to point out that later in De Crayer’s career the influence of Anthony Van Dyck (Rubens most noted pupil) emerges. Critics observe that Van Dyck’s portraits are characterized by a “relaxed elegance.” But this elegance is enriched by a subtle emotional sentiment that intuitively connects the subject to the viewer. These qualities are readily discerned both in Van Dyck’s Self-Portrait (figure 3) and in De Crayer’s portraits of St. Ambrose and St. Augustine from M&G’s collection.

Ambrose was a revered Greek scholar, poet, lawyer, and orator. Trained in politics and law he was literally thrust into an ecclesiastical life. When Auxentius, Bishop of Milan, died in 374 the Arian heresy was on the rise. During the election for the new bishop a violent outbreak seemed inevitable until the 35-year-old Ambrose stood up in the public square and gave an impassioned speech “exhorting the people to proceed in their choice in the spirit of peace.” Following his plea, the whole assembly took up the cry “Ambrose for Bishop.” Although his election astonished him, he determined to take up the task with vigor. Aware of his theological limitations he embarked on an arduous study of Scripture. He also read extensively the writings of the church fathers, especially Origen and Basil. Before long he was revered by both low and high born as a “good shepherd.” The garments he wears in De Crayer’s portrait symbolize his ecclesiastical station.

Ambrose was a revered Greek scholar, poet, lawyer, and orator. Trained in politics and law he was literally thrust into an ecclesiastical life. When Auxentius, Bishop of Milan, died in 374 the Arian heresy was on the rise. During the election for the new bishop a violent outbreak seemed inevitable until the 35-year-old Ambrose stood up in the public square and gave an impassioned speech “exhorting the people to proceed in their choice in the spirit of peace.” Following his plea, the whole assembly took up the cry “Ambrose for Bishop.” Although his election astonished him, he determined to take up the task with vigor. Aware of his theological limitations he embarked on an arduous study of Scripture. He also read extensively the writings of the church fathers, especially Origen and Basil. Before long he was revered by both low and high born as a “good shepherd.” The garments he wears in De Crayer’s portrait symbolize his ecclesiastical station.

Although Ambrose is still counted as one of the great doctors of the Western church, his reputation is overshadowed by his most famous convert, Augustine of Hippo. It is not surprising, therefore, that Gaspar de Crayer would do a companion portrait of Augustine. This work, also part of the M&G collection, was featured as Object of the Month in February 2016.

Augustine acknowledged that Ambrose was the key figure in bringing him to Christ. He records in his Confessions that, “This man of God welcomed me, as a father. As a result, I began to love him, not because of his teaching, but because of his warm and loving personality. I enjoyed hearing him preach, not in order to learn from what he said, but in order to admire and learn to imitate his eloquence. Indeed, I still despised the doctrines he taught. Yet, by opening my heart to the sweetness of his speech, the truth of his teaching began to enter my soul, little by little.” Ambrose would baptize Augustine on Easter morning in 387. Soon after Augustine returned to North Africa where he eventually became Bishop of Hippo, ruling in that turbulent African diocese for 34 years until his death in 430.

Donnalynn Hess M&G Director of Education

Published in 2018