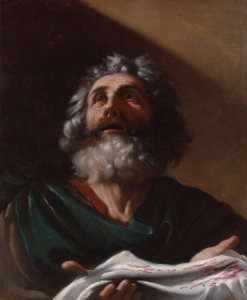

King David Playing the Harp

Oil on canvas, c. 1630s

Simon Vouet

French, 1590-1649

The creator of this moving portrait of King David is Simon Vouet, one of the most influential French Baroque masters. He was the son of painter Laurent Vouet. Although little is known of the elder Vouet’s work, Simon’s oeuvre is well documented, for his prodigious talent emerged at an early age. At 14 he was sent to England to work as a portraitist. Then in his early twenties he moved to Constantinople where he spent two years before traveling to Venice and finally settling in Rome. Vouet’s career flourished in Italy. During this time, he received numerous prestigious commissions, and in 1624 he became president of Rome’s renowned Accademia di San Luca.

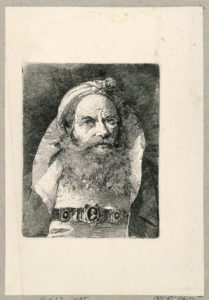

In 1626 he married Italian artist Virginia Vezzi who was regarded as one of Italy’s best miniaturists. The painting to the right (perhaps a self-portrait) is attributed to her. A year after their marriage, the couple returned to France at the request of Louis XIII who promptly appointed Simon official court painter. Vouet became a dominating force in Paris. He was so prolific that it is difficult to create a clear timeline of all the altarpieces, mythological, and devotional works he produced. As one biographer noted, Vouet was a natural academic who studied and absorbed everything in his environment, from the rich color palette of Veronese to the dramatic lighting effects of Caravaggio.

In 1626 he married Italian artist Virginia Vezzi who was regarded as one of Italy’s best miniaturists. The painting to the right (perhaps a self-portrait) is attributed to her. A year after their marriage, the couple returned to France at the request of Louis XIII who promptly appointed Simon official court painter. Vouet became a dominating force in Paris. He was so prolific that it is difficult to create a clear timeline of all the altarpieces, mythological, and devotional works he produced. As one biographer noted, Vouet was a natural academic who studied and absorbed everything in his environment, from the rich color palette of Veronese to the dramatic lighting effects of Caravaggio.

King David, the subject of this portrait, was one of Israel’s most gifted (and complex) kings. He is unique among Old Testament figures by virtue of the fact that he is “fully known.” His remarkable biography is well documented in I and II Samuel, but it is his innermost thoughts revealed through his more than 70 lyric poems (or psalms) that render him most lifelike. Here we come to know “the man after God’s own heart” who despite this intimate relationship with God sins egregiously. Vouet’s masterful technique powerfully captures the complexity of David’s personality.

Although initially captivated by the dramatic naturalism of the Italian Caravaggisti, by the time Vouet returned to Paris, he had integrated classical elements into his painting style. For example, in this portrait the dramatic compositional line and naturalistic portrayal of the aging King is offset by the figure’s classical pose and the diffused (rather than stark) lighting. This stylistic integration of the dramatic and restrained is well-suited to the dualism of the portrait’s iconography.

Color symbolism was prevalent in 16th-century religious art, and often a single color would have more than one meaning. Here, Vouet uses vibrant red and yellow gold fabrics not only to accentuate David’s kingly wealth but also to insinuate the frailty of his nature. In religious iconography, red can symbolize both love and hate, yellow gold sacredness or treachery. All of these qualities are interwoven into David’s complicated history and readily acknowledged by him in his Psalms. In addition, Vouet masterfully captures the emotional depth of “Israel’s singer of songs”(II Samuel 23:1). Notice the intricate detail in the weathered face and hands; notice, too, the tear in the psalmist’s eye as he gazes heavenward and prays. It’s as if we hear him plead: “Hear my prayer, O Lord, and give ear unto my cry; hold not thy peace at my tears: for I am a stranger with thee, and a sojourner, as all my fathers were” (Psalm 39:12). It is not surprising that the harp, David’s attribute, has come to symbolize not just the Psalms but all songs and music created to honor God.

Donnalynn Hess, Director of Education

Published 2022