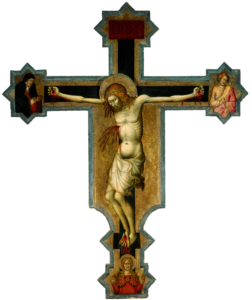

Crucifix

Tempera and gold on panel, c. 1380

Francesco di Vannuccio

Sienese, active c. 1356-1389

Among the many treasures in M&G’s collection hangs a unique and exemplary example of late fourteenth-century Italian art. In 1374, the Black Death struck the city of Siena and its surrounding countryside for the third time in twenty-six years. The return of the plague devastated the city, which was already struggling from political and economic instability. Tragically, most of the victims of this wave of the Black Death were children. In the wake of this period of grief, an unknown patron commissioned Sienese artist Francesco di Vannuccio to paint a crucifix or croce dipinta (painted cross) for his or her church. During the fourteenth century, large painted crucifixes were a fixture in Italian churches. They depicted Christ dead on the cross flanked by Mary and John the Evangelist and were often highly decorated in gold. Positioned above the altar, these crucifixes provided a focal point for worshippers.

Francesco’s patron included an unusual request: the image of Mary Magdalene facing out toward the worshipper with her hands raised in the ancient orans pose of prayer. Of the 214 surviving Italian fourteenth-century crucifixes, only fourteen have Mary Magdalene present. Of those, only one intact crucifix, M&G’s, features this extremely rare imagery of Mary Magdalene. With its unique depiction of a ministering female saint, Francesco’s crucifix was born out of the need for spiritual solace in the aftermath of the Black Death.

Little is known about Francesco di Vannuccio. Few of his paintings survive. He signed only one work, a double-sided panel now housed in Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie. Despite this small surviving body of work, all of Francesco’s paintings demonstrate that he possessed a keen eye for intricate decoration. He was also closely attuned to the religious concerns of his day. Francesco’s depictions of physical and emotional suffering made him stand out among his fellow artists. In his crucifix, Christ’s arms are pulled taut by the weight of His body. His fingers curl and His feet twist around the piercing nails. Blood spurts in a wide arc from the wound in His chest and drips from His head, hands, and feet. While other crucifixes show the mother of Christ serenely grieving, Francesco painted her face deeply lined in anguish. Poignantly, she reaches for her Son, something not seen in any other fourteenth-century crucifixes. Francesco’s Mary is a mother mourning the loss of her Child, a sight many worshippers would have personally related to following the third outbreak of the Black Death.

Beneath Christ’s feet, Mary Magdalene prays. Despite being one of the most popular female saints during the fourteenth century, Mary Magdalene’s presence in crucifixes is rare. Most depict her small in scale contemplating the cross. She does not directly engage with the worshipper as Francesco’s does. During the fourteenth century, Mary Magdalene was revered both as the “blessed sinner” (tradition combined her with the repentant sinful woman in Luke 7) and as the “apostle to the apostles” because of her encounter with the resurrected Christ and her role of spreading the news to His other followers. Painting the blood flowing down to her head and her bright red robes, Francesco depicted Mary Magdalene as being baptized in Christ’s blood. With her hands raised in the orans position and facing the worshipper, Francesco also depicted her as the “apostle to the apostles.” The ancient orans pose represented the worshipper’s openness to God’s grace and was a gestural expression of faith in Christ’s death and resurrection. By the fourteenth century, this prayer position was reserved solely for the clergy. Thus, Francesco’s Mary Magdalene is an apostle actively ministering to the worshippers.

Beneath Christ’s feet, Mary Magdalene prays. Despite being one of the most popular female saints during the fourteenth century, Mary Magdalene’s presence in crucifixes is rare. Most depict her small in scale contemplating the cross. She does not directly engage with the worshipper as Francesco’s does. During the fourteenth century, Mary Magdalene was revered both as the “blessed sinner” (tradition combined her with the repentant sinful woman in Luke 7) and as the “apostle to the apostles” because of her encounter with the resurrected Christ and her role of spreading the news to His other followers. Painting the blood flowing down to her head and her bright red robes, Francesco depicted Mary Magdalene as being baptized in Christ’s blood. With her hands raised in the orans position and facing the worshipper, Francesco also depicted her as the “apostle to the apostles.” The ancient orans pose represented the worshipper’s openness to God’s grace and was a gestural expression of faith in Christ’s death and resurrection. By the fourteenth century, this prayer position was reserved solely for the clergy. Thus, Francesco’s Mary Magdalene is an apostle actively ministering to the worshippers.

Painting Mary Magdalene in this active role, Francesco and his patron were likely inspired by Catherine of Siena (1347-1380). Catherine was a writer and preacher who advocated spiritual reform. She was beloved for her piety and her healing the sick during the third wave of the Black Death. In her ministry, Catherine looked to Mary Magdalene as an example of religious devotion and service. Writing to her female followers, she urged them to “follow the Magdalen, that lovely woman in love, who never let go of the tree of the most holy cross. No, with perseverance she was bathed in the blood of God’s Son…she so filled her memory and heart and understanding with it that she became incapable of loving anything but Christ Jesus.” Mary Magdalene’s love for Christ drove her to brave the Roman soldiers guarding the tomb and proclaim the news of the Resurrection to anyone who would listen.

For worshippers living in the grief-filled years of the late fourteenth century, the sight of Mary Magdalene offered comfort both in the cleansing power of Christ’s sacrifice and His Resurrection. Almost six and a half centuries later, the message of Francesco di Vannuccio’s gleaming cross continues to resonate today.

Dr. Allison Wynne Raper, Adjunct Instructor at York Technical College

For further reading:

Ole J. Benedictow. The Complete History of the Black Death. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 2021.

Catherine of Siena. The Letters of Catherine of Siena. Translated by Suzanne Noffke, O.P. 4 Volumes. Tempe, AZ: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2000-2008.

Katherine Ludwig Janson. The Making of the Magdalene: Preaching and Popular Devotion in Late Medieval Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Published 2024