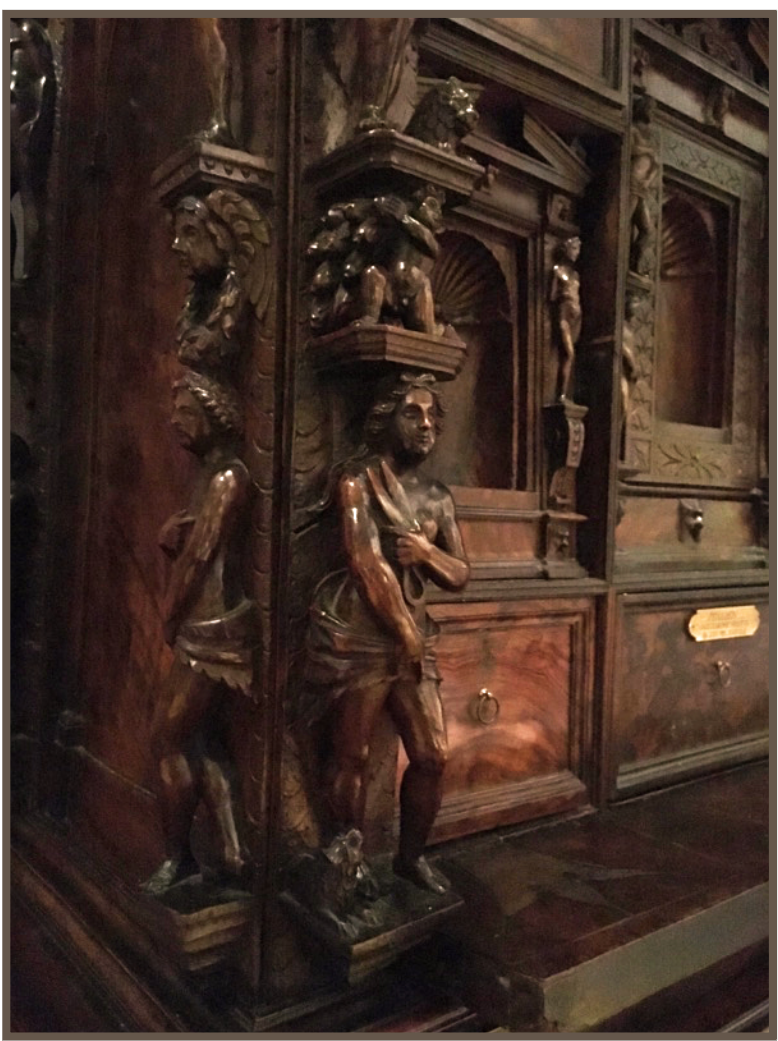

Stipo Bambocci, walnut Stipo Bambocci, walnut

Italian, 16th century Italian, late 16th to early 17th century

Click on links for additional reference information.

Most of us at one time or another have treasured and tucked away some poem, theme paper, or letter. Your paper valuables may have been stashed in a simple cardboard box, but if you were living in Italy between 1560 and the early 1600s in the thriving cities of Genoa or Florence, your written mementos may have been stored in a tall, desk-like piece of furniture called a Stipo a Bambocci, loosely translated “a cabinet with carved babies.” As the style became popular, more iconographic carvings embellished the desk’s exterior, which is typical of the emerging Baroque period. Yet, the name’s association with “babies” persisted.

Beautifully fashioned out of two kinds of wood—burled-walnut and Caucasian walnut, the upper portions of the desks (not usually created at the same time as the lower cabinets) are completely removable, allowing a nobleman to tote just the top portion of his desk on his travels. The interiors, laden with multiple drawers and hidden caverns, beckon the imagination as to what might have been secretly stored within! Most often, a stipo a bambocci was secured with a lockable, fall front writing surface. Supported by lopers when lowered, the false front becomes positioned at a comfortable height for writing.

Beautifully fashioned out of two kinds of wood—burled-walnut and Caucasian walnut, the upper portions of the desks (not usually created at the same time as the lower cabinets) are completely removable, allowing a nobleman to tote just the top portion of his desk on his travels. The interiors, laden with multiple drawers and hidden caverns, beckon the imagination as to what might have been secretly stored within! Most often, a stipo a bambocci was secured with a lockable, fall front writing surface. Supported by lopers when lowered, the false front becomes positioned at a comfortable height for writing.

Mimicking the design of an Iberian desk called a bargueño, the production of stipi (plural for stipo) was short lived, a mere 60 to 70 years. Yet their substantial influence can be seen in a more common piece of furniture today known today as an escritoire or secretary.

Little is known about these early furniture makers; however art historian, Dr. Thomas Meyer, discovered in 2008 that Riccardo Taurini and his workshop were craftsmen of a specific stipo. Meyer notes that the family of Taurini is considered to be the “fathers” of the stipi, blending their designs with inspiration from famous artists, architects and sculptors such as Rosso Fiorentino, Jacques I Androuet du Cerceau, Hugues Sambin, Leon Battista Alberti, Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola, and Andrea Palladio.

Almost as interesting as the desks’ construction are the various personages who formerly owned M&G’s unique pieces—the Royal Family of Savoy; an Austrian Archduke living in Lichtenstein Palace, Vienna; Myron C. Taylor, President Roosevelt’s personal representative to Pope Pius XII during World War II; and the industrialist and avid collector, Carl W. Hamilton of Philippine Refining Corporation. It is intriguing to consider what documents might have once been composed upon or stored within these beautiful pieces of furniture!

Though stipi are most often found today in house museums such as Museo Poldi-Pezzoli, Bagatti-Valsecchi and in the Castello Sforzesco, it is no surprise that M&G has two such unusual desks. M&G’s furniture collection (which includes approximately 100 pieces predominately from the 1400s and 1500s) is almost as renowned as its collection of Old Masters. Joseph Aronson (1898-1976), an international European furniture authority, once remarked that “it is one of the finest collections of Renaissance furniture in America.” Aronson’s work, Furniture in the Bob Jones University Collection, as well as other significant volumes such as A Concise History of Interior Decoration by George Savage and A History of Italian Furniture by William M. Odom, both review these two stipi, and qualify M&G’s collection as a must-see for furniture lovers and historians everywhere.

Bonnie Merkle, Collection Database Manager and Docent

Published in 2017