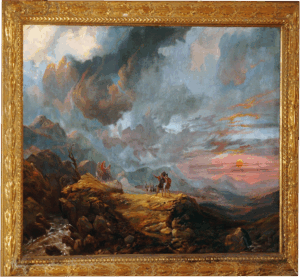

The Trial of Queen Catherine

Oil on canvas, 1880; signed lower left

Laslett John Pott, RBA

English, 1837–1898

The Victorian period is known for its diverse richness as an era of scientific and technological innovation, industry, the development of the novel, the rise of the middle class, incredible social reforms, the expansion of the British empire, and . . . the golden age of English painting.

For us to appreciate the breadth and influence of art during the time, Denys Brook-Hart writes, “the galaxy of artistic talent and endeavour which rose to its peak in the 19th century in Britain had not previously been rivalled in any other country or period. For proof of sheer quantity one needs only to mention the 25,000 professional artists who exhibited in London alone. For quality it is amply sufficient to quote the names of Turner and Constable in their places at the head of a long list of distinguished and truly marvellous artists, many of whom had the rank of genius.”

While being a member and/or an exhibitor of the Royal Academy (founded during King George III’s reign) was considered the height of honor, many other art societies developed before and during Victoria’s rule to train and exhibit artists. Approved by King George IV in 1824, the Royal Society of British Artists (RBA) was organized and began to exhibit annually. Painter Laslett John Pott later became an elected member.

Pott was a child prodigy. Biographers Clare Erskine Clement and Laurence Hutton relate that he “drew cleverly when not more than five years old.” His skill, particularly as a history painter, gave him opportunity to exhibit at least 40 paintings at London’s Royal Academy, beginning in 1860 when he was only twenty-three and including M&G’s painting, The Trial of Queen Catherine in 1880.

Here, Pott conflates two parts of the historical telling into one scene. According to the eyewitness account of Cardinal Wolsey’s gentleman-usher and biographer George Cavendish, Catherine was called to appear before the Legatine Court at Blackfriars where Henry sat upon a canopied dais to watch. Rather than addressing the court, which she felt would legitimize their purpose, she made a rational and impassioned appeal on knee to her seated husband only, then arose, curtsied to the king, and left the hall. The council summoned her to return, but she refused on the grounds that they had already decided against her. Cavendish recounts that later Wolsey met with Catherine for further discussion; however, she strongly and loudly rebuked him for his action motivated by political ambition.

The painting dramatizes the nobility of Catherine of Aragon. She holds her skirt as if she has just risen from kneeling and is preparing to leave after she finishes confronting those from church and state who would declare her marriage of twenty-four years to Henry VIII void—namely, Cardinal Wolsey (standing at the table) and the pope’s emissary, Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio (seated).

Catherine, the youngest daughter of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain, had married Arthur, heir to England’s throne, when she was fifteen. Four months later she was a widow. When she married the next heir to the throne, Henry, she was twenty-three, he only eighteen. Her primary duty as queen, to produce a male heir, was tragically unsuccessful; although she bore six children, none except Mary lived longer than a few months.

Henry argued that the marriage was null since he had violated church law by marrying his brother’s widow, although the pope had granted approval for the marriage. Now desperate for a male heir and enamored with the young Anne Boleyn, the king pressured Wolsey and Campeggio to convince Catherine to agree to their demands. After her refusal, Henry took matters into his own hands and declared himself, not the pope, head of the Church in England, annulled the marriage, and married Anne (who only produced a daughter—Elizabeth). Of course, Henry in pursuit of a male heir found reasons to escape his marriage to Anne, then Jane Seymour, and three subsequent wives.

Erin R. Jones, Executive Director

Sources:

Johnson, Jane. Works Exhibited at the Royal Academy of British Artists 1824-1893 and the New English Art Club 1888-1917w: An Antique Collectors’ Club Research Project. 1974

Erskine, Clara and Hutton, Laurence. Artists of the Nineteenth Century and Their Works. A Handbook Containing Two Thousand and Fifty Biographical Sketches. Boston, 1875

Graves, Algernon. A Dictionary of Artists Who Have Exhibited Works in the Principal London Exhibitions of Oil Paintings from 1760 to 1880. 1884.

Published 2025