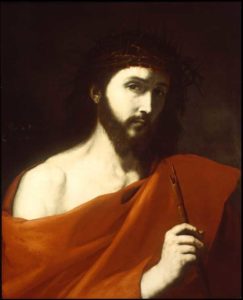

The historical and iconographic details in this early Spanish painting by Jaun de Flandes make it one of M&G’s most intriguing works.

Tag Archives: Spanish art

Watchers and Soldiers from a Crucifixion Group

Polychromed and gilt wood

Although the title Watchers and Soldiers from a Crucifixion Group seems insipid at first read, these two small polychromed and giltwood sculptures provide fascinating insights into an architectural style and installation of extreme magnitude. During the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, the Spanish monarchs who commissioned Columbus’ 1492 voyage to the Americas, the Isabelline style of architecture was developed. Born in France and trained in Flanders, Juan Guas settled in Toledo to establish his business. He is considered one of Spain’s finest architects and one of the key originators of the Isabelline style, which combines a Flemish-Gothic influence with Mudéjar (Spanish-Muslim) ornamentation. His design influence is represented in the monumental edifices at the San Juan de los Reyes and El Paular monasteries.

M&G’s two figural groups date to the second half of the 15th century and according to William Holmes Forsyth, the late curator emeritus of medieval art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “They are from a retable or retablo of Spanish origin, but southern Netherlandish in inspiration.” Beatrice Gilman Proske, the former research curator of sculpture at the Hispanic Society of New York who authored the catalog for the famed outdoor sculptures of Brookgreen Gardens, noted that they are Flemish. It is not then a stretch of scholarship to assume that these two sculptures measuring 32” high by approximately 15” wide, would have commanded a prominent place flanking the carved crucifixion of Christ, a common focal point in many retables from the Low Countries of the time. The Carved Retable of the Passion of Christ, part of the collection at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia, presents a prime example.

At the base of each carving’s scene amidst the jagged rock are bones resembling those from the lower torso and limbs of the human body. These skeletal remains add a sobering reminder that Roman crucifixion included the breaking of the leg bones in order to hasten the impending death. Moreover, the crucifixion of Jesus, as noted by all three synoptic Gospels, occurred on Golgotha or “the place of the skull.”

Positioned on these rocky formations, the Soldiers are each individualized by gaze and weaponry and robed in medieval armor and Moorish headdress, hinting at the Mudéjar influence. The sculptor clearly draws our attention to the only soldier gesturing and glancing upward, perhaps depicting the centurion cited in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and John. Church history, tradition, and pseudepigrapha all ascribe the name of Longinus to this legionnaire, but Scripture allows him to remain anonymous, recording for all time only his striking statements, “Truly this was the Son of God” (Matthew 27:54) and “Certainly this was a righteous man.” (Luke 23:47)

Unlike the soldiers, the Watchers from a Crucifixion Group can be decoded from Bible references, religious iconography, and an abundance of artistic renderings of those who attended Christ’s crucifixion. The repertoire is rich as set forth in examples such as El Greco’s Crucifixion, and Jan Van Eyck’s.

At center front Mary, the mother of Jesus, robed in blue (alluding to heaven, truth, and mourning) and white (for purity and innocence) is comforted by the obviously young apostle John draped in red (for love). On either side of him stand the two Marys, clearly identified in the crucifixion passage in John’s gospel as Mary the wife of Cleophas, and Mary Magdalene (recognized by her long hair as a penitent saint). In the background, towering above the rest of the group, is most likely Joseph of Arimathea, who provided the burial tomb for Christ; he is presented as elderly and robed in the costly garments of the rich. The sculptor carved this individual with an intriguing gesture. With his right index finger raised to his temple, perhaps Joseph is recalling the Scriptures he memorized while serving as a Sanhedrin senator attesting to the deity of Jesus, the Christ.

At center front Mary, the mother of Jesus, robed in blue (alluding to heaven, truth, and mourning) and white (for purity and innocence) is comforted by the obviously young apostle John draped in red (for love). On either side of him stand the two Marys, clearly identified in the crucifixion passage in John’s gospel as Mary the wife of Cleophas, and Mary Magdalene (recognized by her long hair as a penitent saint). In the background, towering above the rest of the group, is most likely Joseph of Arimathea, who provided the burial tomb for Christ; he is presented as elderly and robed in the costly garments of the rich. The sculptor carved this individual with an intriguing gesture. With his right index finger raised to his temple, perhaps Joseph is recalling the Scriptures he memorized while serving as a Sanhedrin senator attesting to the deity of Jesus, the Christ.

Bonnie Merkle, Docent and M&G Databases Manager

For further study:

Heaven’s Backdrop

Retro Tablum: The Origins and Role of the Altarpiece in the Liturgy

Making a Spanish Polychrome Sculpture, J. P. Getty Video

Published in 2019

Cathedra

Walnut

Spanish, mid 15th century

A chair, from the English chaere or Latin cathedra, is one of the most common pieces of furniture and easily identified in its simplest form by its parts—back, seat, arms and legs. The chair’s specific purpose can be discerned by more descriptive names such as recliner, wheelchair, throne, etc. Of course, the person “who takes a seat” can further outline the chair’s scope such as the Queen of England positioned in The Chair in the House of Commons to open a new session of Parliament, a ruling monarch seated on a throne to make a solemn declaration, or a bishop (such as the Pope, known as the Bishop of Rome) adopting a position in a cathedra or cathedrae apostolorum (as it occurs in early church writings) to teach with apostolic authority.

The Museum & Gallery’s furniture collection from the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries is known as the most extensive representation in America and includes several types of ecclesiastical chairs, four of which are cathedrae. Each of the four has interesting designs and carvings, but the oldest in the collection possesses by far the most intriguing and traceable features.

Gazing from the back panel of the Cathedra is a sculpted female figure representing St. Lucy, one of the most venerated female saints in martyrology and mentioned in the Catholic mass itself. She holds two objects: a palm frond, symbolic of victory in death and a platter with eyes, her most common and legendary attribute.

Just under the seat panel is a misericord. Since many of the medieval and early Renaissance ceremonial prayers were uttered in a standing position, the misericord acted as a place to “rest” or lean on during the long ceremony thereby allowing the bishop to obtain a type of “mercy.”

This Spanish Cathedra dates with certainty to the 1400s due mostly to the identifiable coat of arms of Bishop Alonso de Burgos, born in 1415 in Burgos, Spain, the capital of Old Castile. The galero or pilgrim’s hat and tassels were common elements of the crest of a bishop, with the center shield denoting a particular symbol of heritage or character, in this case a lily in the stylized form of a fleur-de-lis, which is a symbol of purity. Alonso’s influence as a bishop was widespread as he served in the central Spain dioceses of Cordoba, Cuenca, and Palencia. Ordained as a Dominican monk at an early age, Alonso so earnestly and diligently applied himself to his vocation as a Catholic clergyman that he was readily noticed and subsequently assigned as confessor by the renowned Catholic Monarchs, a collective term for Spanish King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I, under whose banner Columbus sailed.

This Spanish Cathedra dates with certainty to the 1400s due mostly to the identifiable coat of arms of Bishop Alonso de Burgos, born in 1415 in Burgos, Spain, the capital of Old Castile. The galero or pilgrim’s hat and tassels were common elements of the crest of a bishop, with the center shield denoting a particular symbol of heritage or character, in this case a lily in the stylized form of a fleur-de-lis, which is a symbol of purity. Alonso’s influence as a bishop was widespread as he served in the central Spain dioceses of Cordoba, Cuenca, and Palencia. Ordained as a Dominican monk at an early age, Alonso so earnestly and diligently applied himself to his vocation as a Catholic clergyman that he was readily noticed and subsequently assigned as confessor by the renowned Catholic Monarchs, a collective term for Spanish King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I, under whose banner Columbus sailed.

Beyond being instrumental in the financing of some of the voyages of the discoverer, Bishop Alonso’s influence was exhibited in founding a center for Dominican study, the Collegio de San Gregorio, an Isabelline-style building located in the city of Valladolid. Readily visible throughout the architecture is Alonso’s heraldry.

Beyond being instrumental in the financing of some of the voyages of the discoverer, Bishop Alonso’s influence was exhibited in founding a center for Dominican study, the Collegio de San Gregorio, an Isabelline-style building located in the city of Valladolid. Readily visible throughout the architecture is Alonso’s heraldry.

Bonnie Merkle, M&G Docent and Database Manager

Published in 2019