Orazio de’ Ferrari skillfully captures one of the Old Testament’s most powerful stories.

Category Archives: Instagram

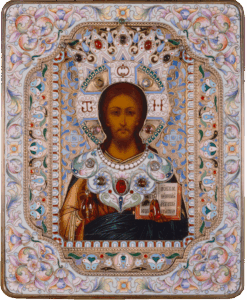

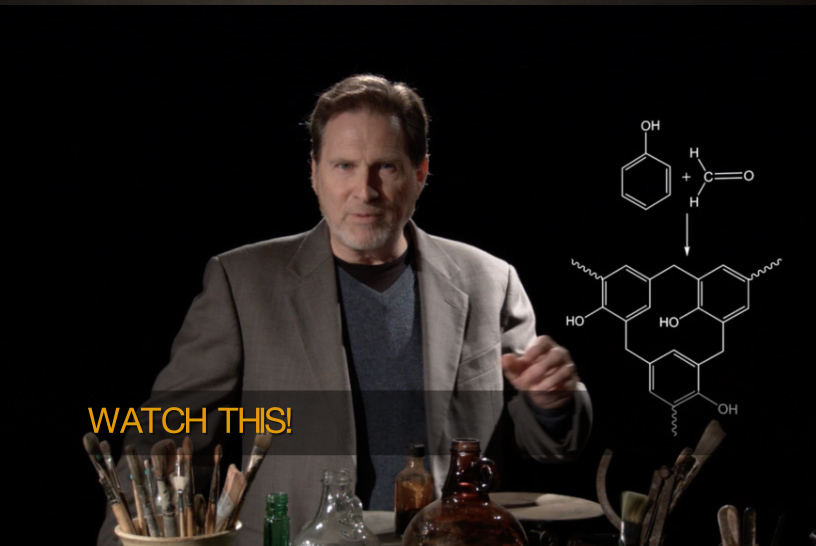

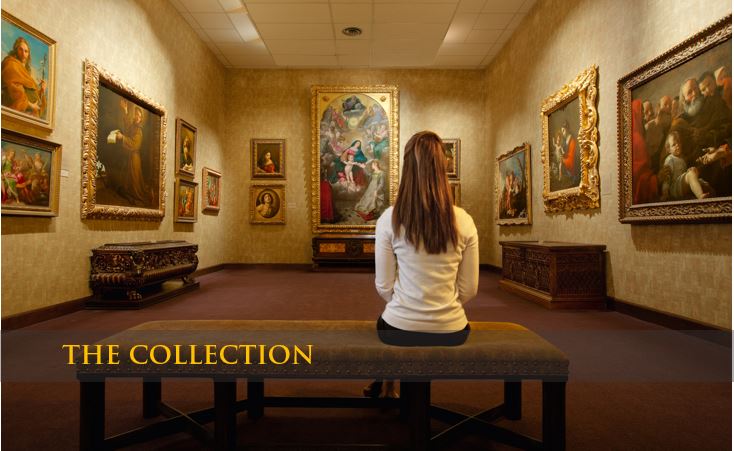

Old Master paintings can be overwhelming sometimes with their detailed beauty, serious palette, and historical roots. But they don’t have to be, which is why M&G created the EXPLORE pages—a diversion on our website to unfold some of the mystery and meaning in the art of the past. Watch, listen, read, and color your way through the world of Old Masters!

Click on the links below to investigate for yourself:

The Museum & Gallery is a non-profit organization that depends on the financial support of individuals, businesses, and foundations. Your tax-deductible contribution helps M&G to continue transforming lives through our European Old Master Collection and outreach programs for students of all ages!

We’ve added this page to help you consider some of the most popular ways to give to M&G. You can learn about strategies for giving today and strategies for giving in the future. We’ve even included a few once-in-a lifetime strategies. Just click on the arrows below for further information.

We welcome the opportunity to equip you with additional information about any of these giving methods and to discuss with you the best strategies for you to consider. We’re also available to connect with your personal legal, tax and investment professionals. Contact us at contact@museumandgallery.org or 864-770-1331.

Giving Today

Giving Cash

Cash giving is your quickest and easiest way to invest in M&G’s mission of transforming lives through fine art. If you itemize rather than take the standard deduction on your federal income taxes, you can deduct cash gifts up to 60% of your adjusted gross income through 2025 and 50% thereafter. In fact, gifts of cash are one of the surest ways to make your itemized deductions exceed your standard deduction.

- Giving by check: make your check payable to Museum & Gallery, Inc. and mail to:

- Museum & Gallery, Inc.

1700 Wade Hampton Blvd.

Greenville, SC 29614

- Museum & Gallery, Inc.

- Giving online by debit card or credit card: please click here to use our secure form.

- Giving by phone: please call (864) 770-1331

- Giving by wire: please contact us for instructions at (864) 770-1331 or contact@museumandgallery.org.

Giving from Your Donor Advised Fund

If you have a donor-advised fund at the National Christian Foundation, South Carolina Christian Foundation, your local community foundation, or you utilize a gift fund with Fidelity, Vanguard, Schwab, or other investment firm, you can suggest gifts be made from your fund to M&G. Be sure to instruct the foundation or fund to share your identity with us so that we can thank you for your gift.

Giving from Your Investment Portfolio

When you give shares of appreciated stock, mutual funds, or bonds you’ve owned longer than 1 year directly to M&G, you make an easy, lower-cost, tax-effective gift.

Gifts from investments that have grown allow you:

- To make a generous gift today and not impact your cashflow from your other sources of income;

- To reduce the built-in capital gains tax bill that will eventually come with a portfolio increasing in value.

Plus, if you itemize, you’ll likely increase your deductions and pay less income tax. Your deduction amount would be for the value of the stock on the day the gift is received and not on the price you paid for it. You can deduct the value of the stock gift up to 30% of your adjusted gross income.

For gift of stock instructions, please contact us at (864) 770-1331 or contact@museumandgallery.org.

Giving through Your Employer’s Matching Gift Program

Your employer may offer a matching gift program to double the impact of your gift. To find out if your company has a matching gift policy, please contact your Human Resource department. If your gift is eligible, request a matching gift form from your employer, and send it completed and signed with your gift to M&G. We will do the rest!

Giving from Your IRA Now (QCDs)

If you are age 70½ or better, your traditional IRA may be the best source for your annual or special project giving.

Qualified Charitable Distributions—QCDs—allow you to give funds from your IRA directly to M&G. For 2024, you can give up to $105,000, and the gift counts toward your required minimum distributions which take effect once you reach age 72 (73 if you reach age 72 after Dec. 31, 2022).

This strategy could be a benefit if you would rather make a generous gift today than recognize the taxable income from some or all of your IRA distribution once you’re required to take distributions. For Planning Tips and simple instructions, download our QCD tip-sheet.

Giving in the Future

Giving through Your Will or Trust

You can give to M&G through your will or trust and know that you will be transforming lives through fine art for years to come. These gifts—known as bequests—are a great way to memorialize your legacy of giving to M&G or make a major gift without impacting your current cash flow or available assets.

Through your will or trust, you can give:

- A specific amount or a specific asset,

- A percentage of your estate (the most common!), or

- What’s left of your estate after gifts to other beneficiaries.

Additionally, your gift can be contingent on your spouse or other beneficiaries predeceasing you.

Giving through Your Life Insurance

The simplest way to give using a life insurance policy is to name M&G as a beneficiary of the policy. You can use the policy to benefit loved ones and M&G, M&G if your loved ones predecease you, or M&G exclusively.

You can also transfer ownership of the policy to M&G. If it’s permanent insurance, we can liquidate the policy and put the cash value to immediate use, or you can continue paying the premiums on the policy to M&G. The paying of the premiums to M&G create additional charitable deductions.

Giving through Your Retirement Plan or IRA

With a simple beneficiary designation form provided by your plan administrator, you can name M&G as a contingent, partial, or exclusive beneficiary of your unused retirement plan or IRA balance. This is a great way to make a significant gift in the future without impacting investment growth before retirement or cashflow during retirement.

If your retirement assets are funded pre-tax—like a traditional IRA or 401(k)—your loved ones will pay income tax on distributions to them at their tax rate. M&G will benefit from the total of any distribution without any tax reduction in the value of your gift. Additionally, naming M&G as a beneficiary may generate estate tax savings.

When making a future gift by beneficiary designation, please include the following information to ensure your gift is realized:

- Museum & Gallery, Inc.

1700 Wade Hampton Blvd.

Greenville, SC 29614 - M&G’s EIN: 57-0956189

The Museum & Gallery Legacy Society – We Want to Celebrate You!

If you have included a gift for M&G in your will or trust or by other beneficiary designation, please let us know. We would like to thank you and celebrate your gift. We can also prepare in advance to honor your wishes and preserve your legacy until Christ returns.

The memory of the righteous is a blessing.

Proverbs 10:7

Once-in-a Lifetime Legacy Opportunities

Giving Your Real Estate

Your primary residence, vacation home, vacant land, or commercial property are all assets that you could give M&G. If not for M&G’s own real estate needs, the property can be sold by M&G and the proceeds put to work in programming, art acquisition, or added to the endowment.

- Giving it Now: Real estate given during your lifetime can generate a significant charitable income tax deduction based on the fair market value of the real estate. Plus, you avoid paying capital gains tax on the sale of the property.

- Giving it Later: You can give your real estate to M&G after you’re done enjoying it either:

- Through your will or trust, or

- By transferring it now but keeping a life estate for your lifetime.

Giving of Your Business

If you’re an entrepreneur, whenever you first think about selling your business or are planning the transfer of your business to your children or partners, you have an opportunity to make a generous gift to M&G. You can often generate a significant charitable income tax deduction and reduce your capital gains tax.

Planning Tip: If you would like to explore making a gift for the sale of your business, the ownership interest or shares in your business must be transferred to M&G before you have a contract for sale of your business. Be sure to consult with your legal and tax advisors early.

We’re Here for You

If you have any questions or want to explore your personal options, please contact us at contact@museumandgallery.org or 864-770-1331.

Where we choose to store our treasures depends largely on where we think our home is.

Randy Alcorn