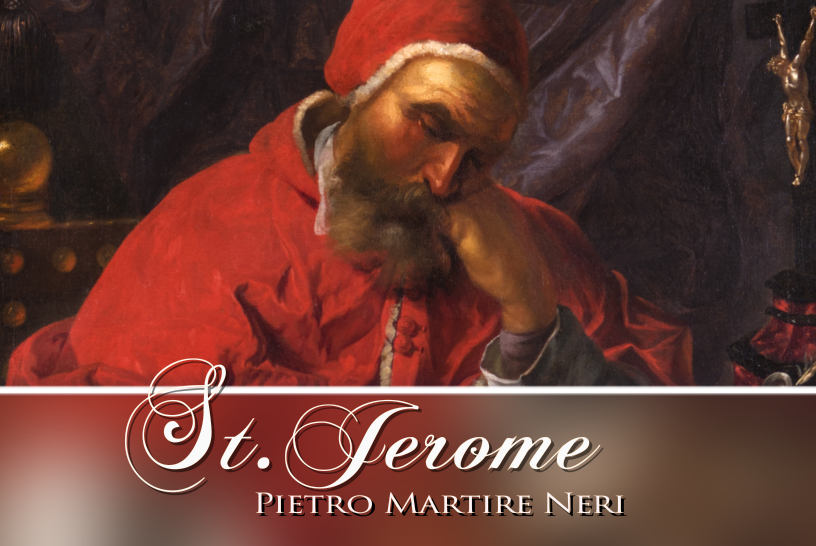

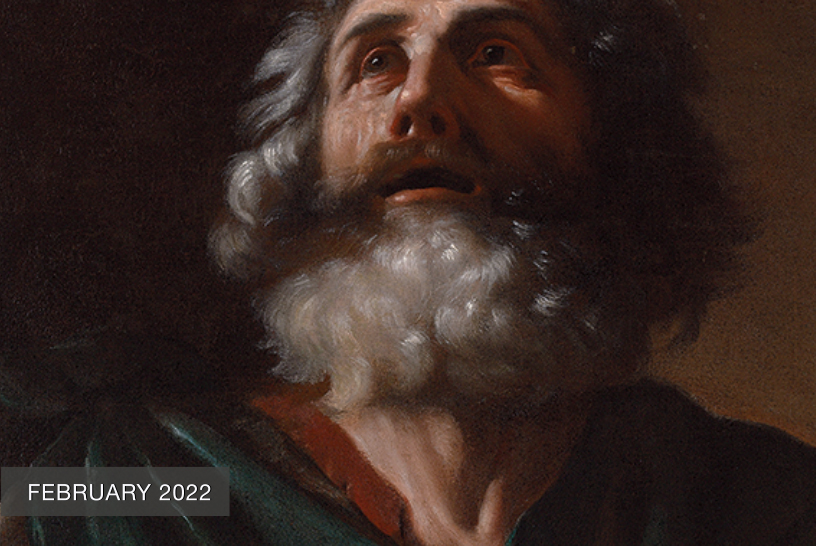

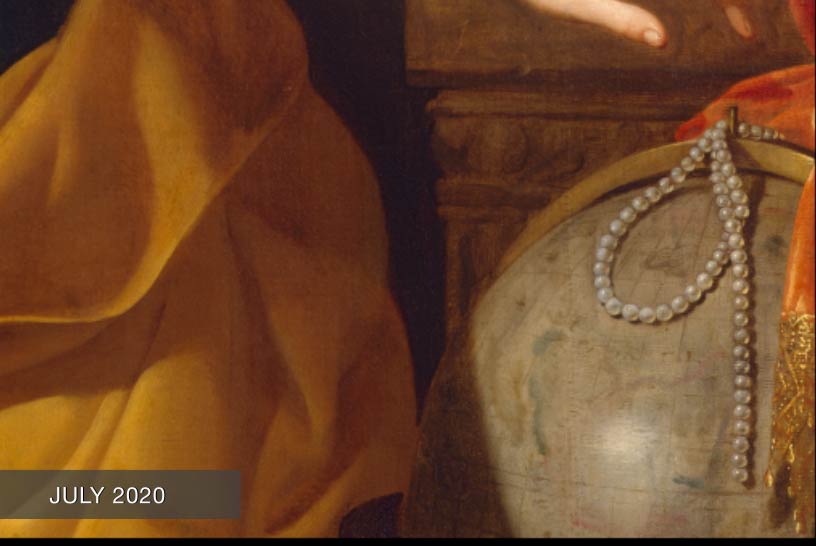

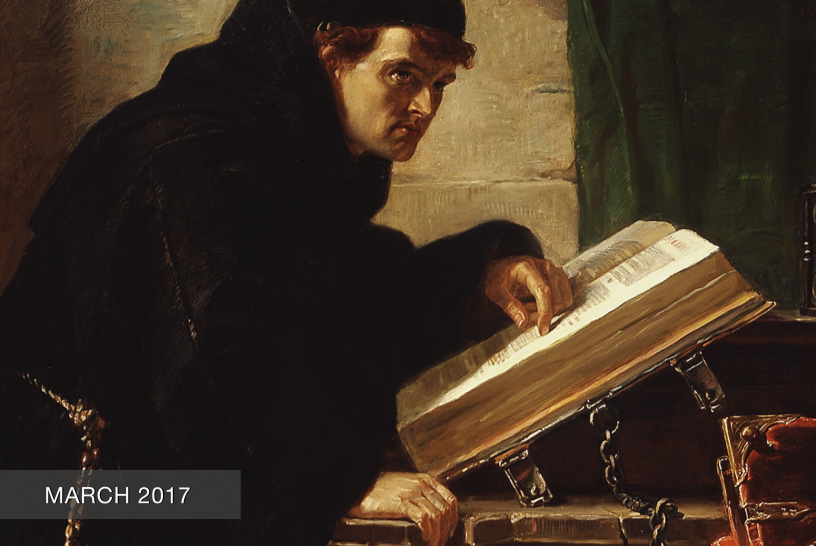

Although little is known about the Italian artist Pietro Martire Neri, this portrait illustrates his stunning mastery of beautiful coloration and intricate stylistic detail.

Tag Archives: old master

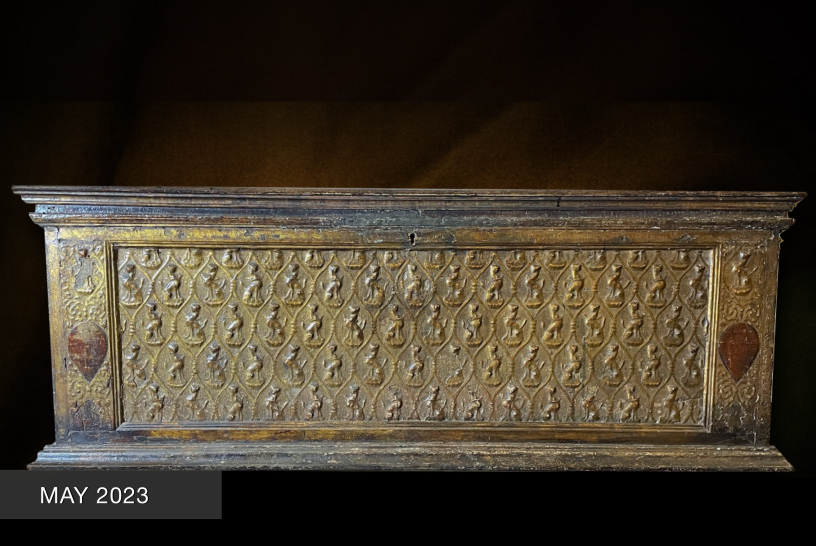

As we continue to make more works available online, survey some of the paintings and objects in M&G’s collection. Click on the images below to enjoy videos, articles, and audio stops.

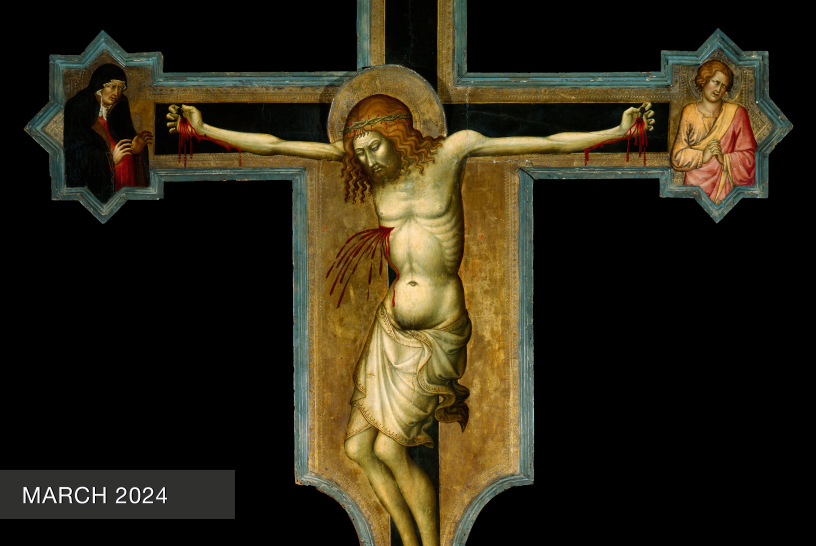

St. Sebastian

Oil on panel, c. 1529–30

Andrea d’Agnolo, called del Sarto (studio of)

Florentine, 1486–1530

Andrea d’Agnolo grew up in Florence and was nicknamed del Sarto meaning “of the tailor” after his father’s profession. Like other early Renaissance artists, he initially trained with a goldsmith, then studied under a series of three separate painters until he began producing his own works in 1506. He spent most of his life in Florence—except for a visit to Rome and a brief stint as court painter to King François I at Fontainebleau in 1518.

As the son of a tailor, del Sarto’s works reveal a unique understanding and love of fabrics—even seen in his 1517-1518 Portrait of a Young Man in London’s National Gallery, which may be a self-portrait (on right). Notice the finishes of the puffed sleeve, ruched white undershirt, and the vest’s seam at the shoulder.

As the son of a tailor, del Sarto’s works reveal a unique understanding and love of fabrics—even seen in his 1517-1518 Portrait of a Young Man in London’s National Gallery, which may be a self-portrait (on right). Notice the finishes of the puffed sleeve, ruched white undershirt, and the vest’s seam at the shoulder.

Andrea was also influenced by his contemporaries who outlived him: Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael. Once these masters left Florence for other parts of Italy, Andrea became Florence’s leading artist in the early 1500s. He is overlooked in art history; yet he is equal in skill and quality to the three greats, and his works are beautiful and still revered today. Julian Brooks, curator of drawings at the Getty, recognizes del Sarto as the “revolutionary engine of the Renaissance and the transformer of draughtsmanship” due to his careful and creative preparatory drawings, a practice which inspired the next generations of artists to follow.

However, he has been underappreciated, even to the point of his students overshadowing him to become famous including Rosso Fiorentino, Jacopo da Pontormo, and Giorgio Vasari, biographer of contemporary Renaissance artists. Vasari records details about his teacher as related to M&G’s work. A Florentine charitable organization for plague victims, the Company of St. Sebastian commissioned Andrea del Sarto to paint a picture of St. Sebastian, the patron saint for plague victims. He became a member of the Company in February 1529, perhaps as a result of negotiations surrounding the commission. Ironically, shortly after completing the painting in 1530 during Florence’s plague epidemic, del Sarto died from the plague at 44 years old.

Several 17th-century documents list the original St. Sebastian as the property of the Company of St. Sebastian. Publications in 1759 and 1770 mention that the painting moved to the Pitti Palace in Florence. By the early 19th century, writers could no longer trace the location of the original painting—apparently it was removed from the Pitti Palace and lost.

M&G acquired St. Sebastian in 1970 from the former great British collection of the Cook family. In 2005, the National Gallery of Canada requested St. Sebastian to participate in an exhibition, and we sent our work in advance for study and conservation. The conservator Stephen Gritt found, “In its materials and construction, the painting is entirely consistent with one from Sarto’s workshop. The complete absence of any change in the design from the drawing stage on the panel through to the painting would indicate perhaps that the design had reached a point of satisfactory refinement by the time this version was produced. While this may mean that some artist other than Sarto could have painted the work, it does not exclude his participation in its production as a supervisor.”

Regarding del Sarto’s workshop practice, Julian Brooks notes that “Andrea would have been closely involved in the production of all versions, or at least those produced in his workshop during his lifetime, and these were produced side by side in the studio.” He also made, used, and reused partial cartoons.

It is difficult to confidently confirm if M&G’s St. Sebastian is the missing painting by the master, thus the current attribution, studio of Andrea del Sarto. At the least, someone very close to del Sarto painted the work. Found in Italy, Spain, England, and Austria, more than 10 other variants of the St. Sebastian exist. Even so, M&G’s is considered by specialists as the “best surviving reflection of the original.”

Erin R. Jones, Executive Director

Resources:

- Getty: www.getty.edu/art/collection/person/103JXC

- Julian Brooks’ lecture for the 2019 exhibition at the Frick, Andrea del Sarto: The Tailor’s Son and the Making of Masterpieces: www.youtube.com/watch?v=PJSkeIJgdzw

- Leonardo Da Vinci, Michelangelo, and the Renaissance in Florence, edited by David Franklin

- Andrea del Sarto: The Renaissance Workshop in Action, Julian Brooks with Denise Allen and Xavier F. Salomon

Published 2023

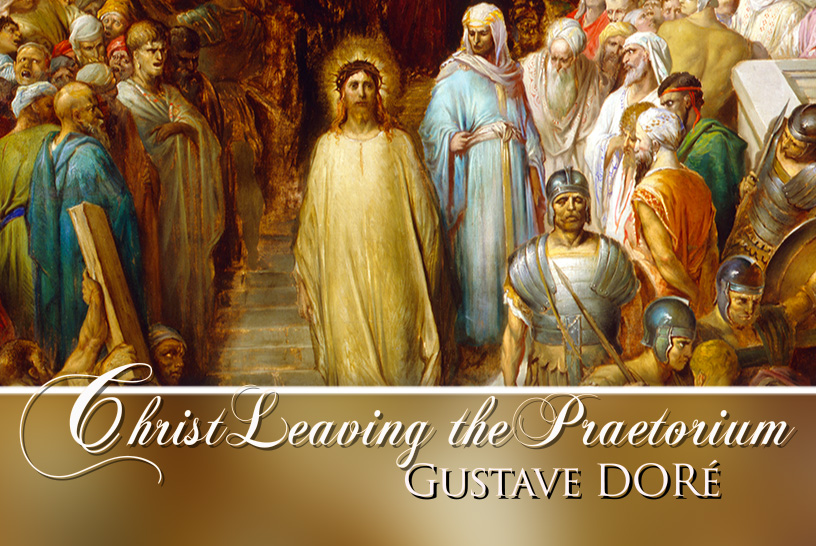

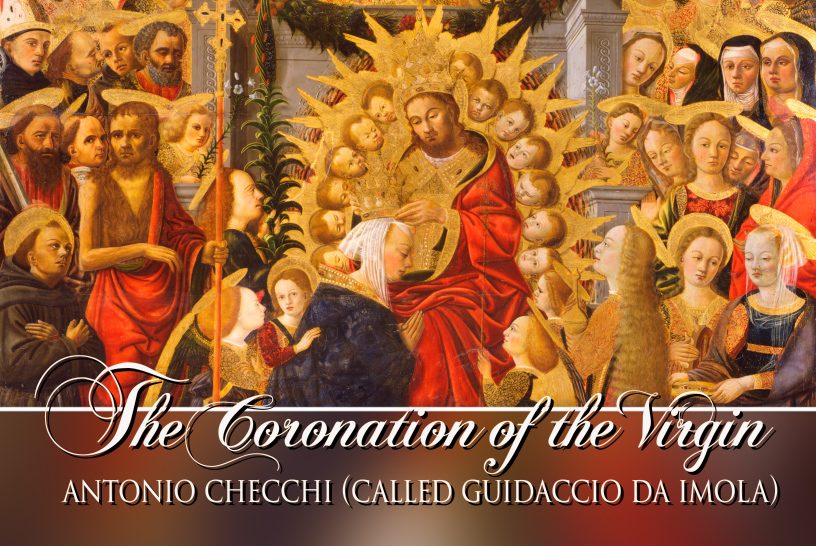

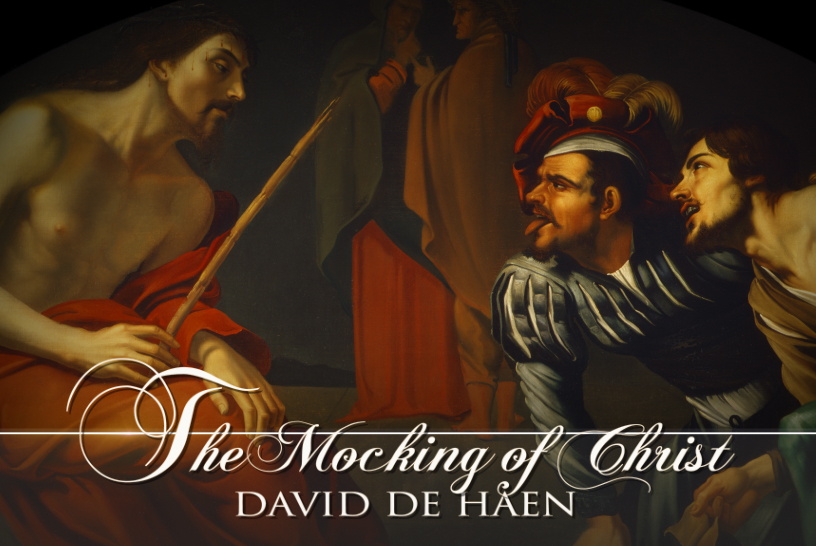

This is the only signed picture by this early Italian master. It also includes 55 faces!